Building the Communist dream

Imagine Moscow, an exhibition at London’s Design Museum, captures an architectural future that never was.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In revolutionary climates, literally anything seems possible. Not only can streets, cities and states be renamed, even the calendar can be reorganised. Everything can be engineered towards the goal of reforming and reformulating existence.

The Bolshevik-led October Revolution ushered in a new era in what would become the USSR. Not only would political and economic systems be abolished and replaced by Communism, there would be a project to create ‘Soviet Man’, which would entail re-education of men and women previously shackled by the bourgeois capitalism that existed under Russia’s monarchical tyranny. The individual was no longer considered a private person with concealed (and potentially suspect) beliefs and selfish interests; Soviet Man would control the means of production and govern the state as part of a collective. But in return he must forgo his private self-interest.

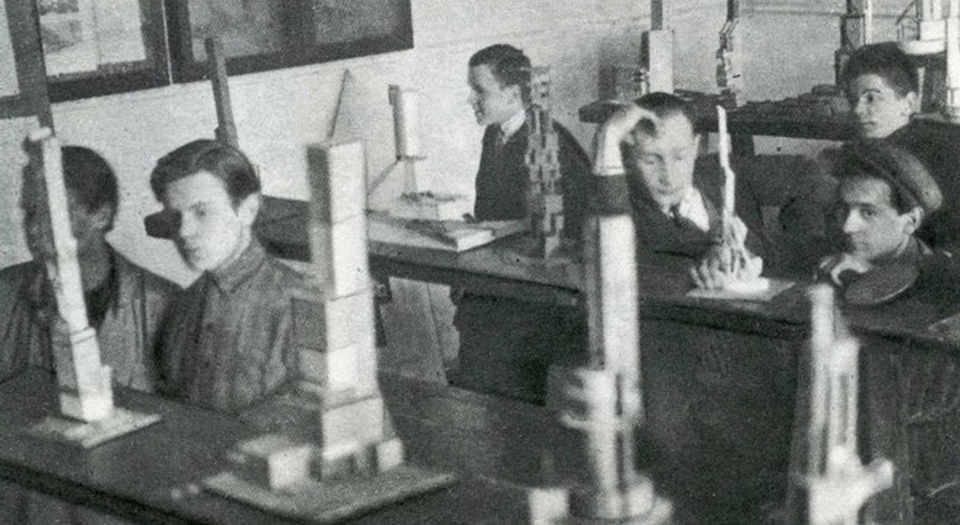

Architecture was to play a crucial role in the revolutionary intention to create Soviet Man. This is captured by Imagine Moscow, a new exhibition of art, textiles, posters and architectural plans at London’s Design Museum, which examines six Soviet architectural projects for Moscow, dating from the 1920s and 1930s.

The USSR of 1917 to 1926 was a land where the most radical of ideas were taken seriously and even encouraged by the new regime. It was also a largely rural economy with an impoverished, under-educated population. In its early years it was also fighting a bitter civil war. The imagination of urban intellectuals and city planners far outstripped the resources, knowledge and funds available for many projects, even those that were relatively modest. And the most ambitious plans were those most likely to be shelved.

Prior to the revolution, a small group of vanguard Russian Modernists had worked in Tsarist Russia. They were inspired by the developments in Western Europe, and had developed their own styles, such as Constructivism and Suprematism. They were keen to have their ideas reach fruition in more public forms. In the early years of the revolution, political leaders were attracted to these radical ideas for two principal reasons. First, they demonstrated a break with religious and bourgeois tradition. Modernism embodied precisely the aspirational adventurousness that the Bolsheviks were keen to harness in order to inspire worldwide progression to universal co-operation, and to realise mankind’s full potential. Second, Modernism proposed some ambitious pragmatic solutions to problems that had previously seemed insoluble due to political, social and religious constraints. The inertia of capitalism in Tsarist Russia that had prevented wholesale change was no longer applicable in the USSR.

Some of the exhibited designs are an extension of Suprematist and Constructivist painting styles: geometric, bold and simplified. Many of the designs are at the conceptual stage and do not elaborate on the practical and engineering solutions that would have been needed to realise these dramatic visions. Textile designs and posters show how the cult of technological progress and industrial production were disseminated.

Designs for communal houses demonstrate how radically the USSR intended to disrupt discrete cells of familial privacy. After all, families and couples naturally carved our their own private spheres, perpetuating traditional values and resisting Communist policy. These private groups would be broken down through the use of collective accommodation, communal living, shared parenting and organised group activities. Older children would be separated from their parents. The emancipation of women was to be affected by the abolition of the nuclear family. Women were needed as workers in all fields of production and were encouraged to pursue technical vocations as well as scientific study.

The huge Palace of the Soviets was to be a symbol of Communism’s superiority over competing ideologies. It would have been the tallest building in the world (416 metres), surmounted by the world’s tallest sculpture: a 100-metre-high statue of Lenin. Architecturally, it was a melange, consisting of a classical Roman base below a round skyscraper tower of multiple tiers. The thinking behind the Palace of the Soviets, as El Lissitzky argued, was that the USSR would perfect the idioms and technology of capitalism. Commissioned between 1931 and 1933, the winning design by Boris Iofan was never realised. Only the foundations had been laid by the time the Second World War halted construction. In 1994 even this trace was erased by the construction of a replica of the Tsarist-era cathedral which had once existed on that site.

Konstantin Melinkov’s design for the Commissariat of Heavy Industry, with an upright circular aperture echoing a gigantic hollow wheel, has the feeling of a Piranesian prison: a vast structure which crushes the individual’s ego with its relentlessly inhuman scale. That hyperinflation of size and domineering presence are two aspects Communist public architecture share with Fascist architecture. In contrast, some of Ivan Leonidov’s designs for monuments and buildings are general and impressionistic, amounting to Romantic paintings of ill-defined fantasies.

By the early 1930s, the official style of the USSR was Socialist Realism: idealistic and realistically painted scenes of healthy schoolchildren, heroic soldiers and productive workers. Geometric art was seen as alienating and obscure; museum directors consigned most art in that style to the storerooms. Visionary Suprematist painter Malevich ended his days painting semi-realistic portraits. Although Modernist and Brutalist architecture were the common Soviet styles for public buildings, this produced pragmatic compromise and unadorned functionalism instead of avant-garde idealism. The idea of the Soviet revolution embodied in architecture had been snuffed out within two decades, which makes Imagine Moscow’s glimpses of a future that never was all the more intriguing and poignant.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

Imagine Moscow is at the Design Museum until 4 June 2017.

Picture by Wikimedia Commons.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.