Alabama: a blow to Trumpism

Trump is weaker than ever. But Democrats shouldn’t be complacent.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

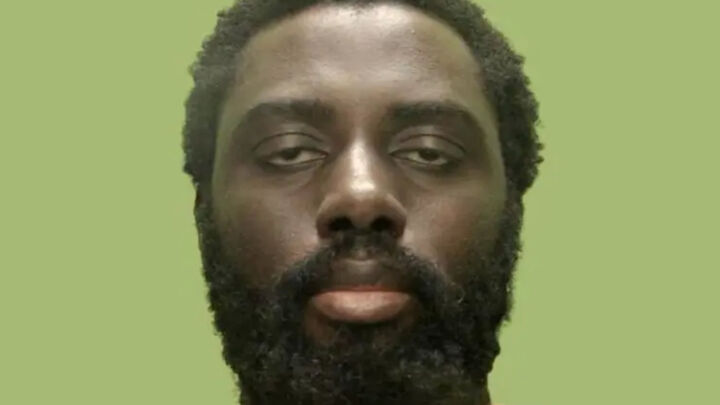

En route to losing the Alabama Senate race, credibly accused child molester and twice defrocked judge Roy Moore won 80 per cent of white evangelical voters. He didn’t run as an economic reformer intent on taking care of the working class. He ran as a Christian nationalist, known for elevating his view of God’s law over the civil laws of state. He ran as a retrograde culture warrior, who expressed nostalgia for slavery and favoured repealing all constitutional amendments that followed the Bill of Rights, which include amendments abolishing slavery, guaranteeing equal protection, and enfranchising women, as well as former slaves. And, of course, he ran as a fervent opponent of abortion rights.

Senator-elect Doug Jones is unapologetically pro-choice, which in the view of evangelical voters, means he is pro-murder. Faced with a choice between a ‘baby killer’ and an alleged child molester, many chose the latter. Jones won over some Republican or Republican-leaning voters, especially among women, and would likely have garnered more had he run on an anti-abortion platform.

The Alabama election was, in part, a culture war, because Roy Moore, and not Doug Jones, is a culture warrior. Jones won narrowly, not by ginning up cultural divides, but, by all accounts, because he ran a kitchen-table campaign, focused on issues like healthcare, and had a superior get-out-the-vote operation: his campaign volunteers reportedly knocked on over half a million doors. Moore, touting his theocratic aspirations, his fierce opposition to gay rights, immigration and abortion, and relying on the support of white nationalist Steve Bannon, tried to win the old-fashioned southern way.

His candidacy was an angry stand by a dying culture, a battle between the new and old south, in the view of National Review columnist and native southerner David French. Roy Moore was the ‘zombie manifestation of the Old South’, French writes. ‘His supporters and apologists were walking, talking caricatures of the region’s very worst.’

This was particularly apparent to black voters, whose participation surged to 30 per cent of the electorate; almost all of them, 96 per cent, voted for Jones. At the same time ‘the New South’s Republicans went on strike’, French notes, declining to vote the party line.

Still, while Democrats and conservative Republican intellectuals like French celebrate Moore’s defeat, it’s worth remembering that he nearly won. The electorate was split in half, with 48.4 per cent supporting Moore and 49.9 per cent supporting Jones. Both parties have reason to hope and fear.

For the next year the Senate will be even more narrowly split between 49 Democrats and 51 Republicans, including two or three who may not always vote the party line. But Democratic chances of winning back the Senate in 2018 (and taking back control of lifetime federal judicial appointments) remain quite slim. Democrats have 26 seats to defend, including 10 in states that voted for Trump, while Republicans have only nine Senators up for re-election. They have a better chance of taking back the House of Representatives, but it remains greatly complicated by gerrymandering, as well as recently erected legal barriers to voting, mainly affecting the Democratic electorate; they’re ostensibly designed to curb voter fraud – which is so small that it’s irrelevant.

Nonetheless, Democrats are buoyed by recent victories in Virginia and New Jersey, as well as in Alabama, by the disproportionate support of young voters and women and the surge in turn-out of black voters. But they won’t be running against malignant cranks like Roy Moore, and they will be contending with the competing demands of their base and the Obama voters who deserted them for Donald Trump in 2016. But balancing the concerns, beliefs and biases of diverse groups of voters is an inevitable, perennial political problem. Campaigns are exercises in coalition-building, and coalition-building is an exercise in arithmetic. Appeal to the values of one group of voters and you’re apt to lose another.

Republicans have their own challenges, not the least of which may be voter disenchantment with an increasingly angry and erratic Donald Trump, who was unable to persuade his base in Alabama to turn out for Roy Moore: Trump’s approval rating is down even in this deep-red state. If he is politically diminished in the wake of Moore’s defeat, he’ll exert diminished influence over Republicans in the House and Senate, where his support is wide but shallow. Some reportedly defend him now partly in the hope of restraining him in a crisis, or perhaps even holding him accountable, if he loses his grip on their voters.

In these extraordinarily abnormal times no one can predict how closeted anti-Trump Republicans will react if or when the president fires special prosecutor Robert Mueller, for example, or if Democrats manage to take back the House and initiate impeachment proceedings. No one can predict what constitutional crisis this bizarre president will spark, but we can surely sense that one is coming.

Wendy Kaminer is a lawyer and writer, and a former national board member of the American Civil Liberties Union. She is the author of several books, including: I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional (1992); and Worst Instincts: Cowardice, Conformity and the ACLU (2009).

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.