The forgotten First Amendment freedom

A free press remains the lifelong partner of free speech.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Freedom of the press is out of fashion across the Western world. Yet it is as important as free speech to a free society.

In the UK, the first state-backed system of press regulation for more than 300 years is about to begin – via the Royal Charter agreed by all of the political parties in a deal with the tabloid-bashing lobby Hacked Off. A new law will impose potentially punitive costs on publications that refuse to bend the knee and sign up – which so far includes all of the national press.

In the US, the First Amendment to the Constitution still prevents such legal regulation. Yet there, too, an influential lobby is pushing for greater state intervention to tame the press and media – for example, demanding that the Supreme Court afford less protection to ‘lower value’ forms of published speech, or government intervention to enforce a mandatory ‘right to reply’ on the press and even subsidise a more ‘serious’ (that is, sanitised) media.

Meanwhile, the creeping culture of You Can’t Say That seeks to impose more informal restrictions on the freedom of the press on both sides of the Atlantic.

The strange thing is that many of those who show such disdain for press freedom today would identify themselves as liberal supporters of free speech. They try to make a distinction between free speech for individuals (seen as a Good Thing) and freedom of the press (Not Necessarily So).

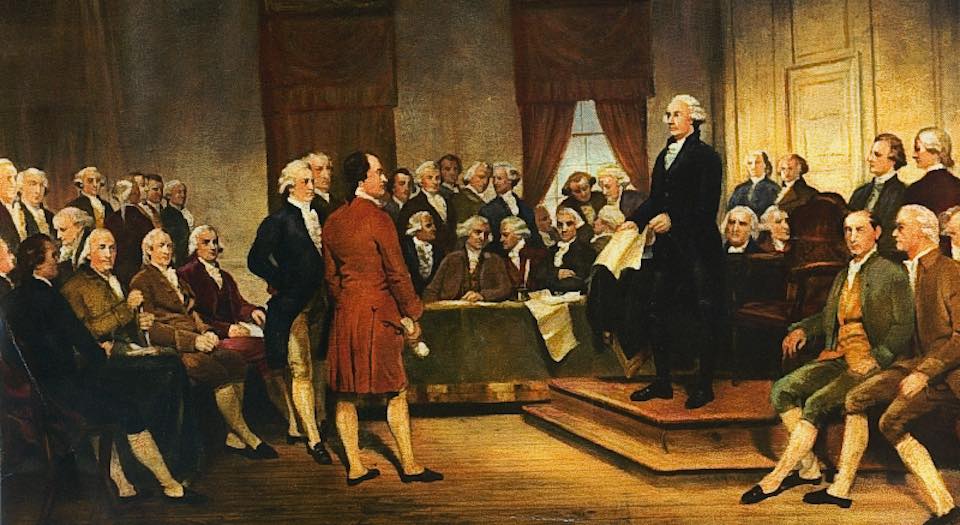

Those who want to separate free speech from freedom of the press only demonstrate that they don’t really support either. These two liberties are and always have been inseparable. There are good historical reasons why the First Amendment to the US Constitution has, since 1791, coupled them together to be jointly and equally protected from state interference, declaring that ‘Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press’.

From the beginning, the demand for free speech was focused on freedom of the press – which meant the printing press. The modern struggle began in earnest from the seventeenth century in Britain and then America. It was not about an abstract wish for freedom of expression, but a specific demand for an end to state control of the published word.

The precursor to the fight for free speech — the demand for freedom of conscience — was about the liberty of the individual privately to believe what he thought true, not what he was told to believe by the political and religious authorities. The demand for freedom of speech went a step further, seeking the liberty to express those beliefs and opinions in public. And how was such public freedom of expression to be made effective? Primarily through the printing press, which made it possible to popularise ideas on a wide scale for the first time.

That was why the struggle for free speech focused, first in Britain and then in the American colonies, on attempts to end the system of state licensing. These laws gave the Crown control over everything that was printed, and could send those convicted of publishing unlicensed ‘seditious libels’ that criticised the government to jail or the gallows.

In the first wave of the free-speech wars in England, those demanding freedom of the press were religious heretics who wanted first a Bible printed in English rather than Latin, and then the liberty to express their Puritan and non-conformist creed. Their clash with the censorious power of central authority soon melded into a rising political clamour for freedom of the press. As the English Civil War broke out between the king and parliament in the 1640s, the demand for freedom of the press was at the forefront of the movement for political and social change, led by the ‘revolt of the pamphleteers’. John Lilburne of the radical Levellers demanded of parliament ‘that you will open the press, whereby all treacherous and tyrannical designs may be the easier discovered, and so prevented’.

Crown licensing of the press formally ended in 1695. Yet in the late eighteenth century, English radicals such as John Wilkes were still fighting for the freedom to publish what they saw fit, criticise the king’s government and report the proceedings of parliament without the threat of being sent to the Tower. The ‘liberty of the press’, declared the front page of Wilkes’ notorious newspaper, was ‘the birthright of every Briton’.

That belief in the freedom of the press as the lifeblood of a free society spread to America. The revolutionary demand for independence from Britain took hold thanks in no small part to the radical publications that Americans had fought for the freedom to print. Looking back on these momentous events, the second US president, John Adams, reflected that the war for independence that began in 1775 was not the real revolution. That, said Adams, had been the revolution in the hearts and minds of the people, the spark for which had been pamphlets and newspapers ‘by which the public opinion had been enlightened and informed’. Freedom of the press had proved the catalyst for the creation of a free nation. Little wonder that it was to be embedded in the US Constitution by the First Amendment.

Yet today, freedom of the press is often looked down upon in high-minded liberal circles, as if it were some sort of corporate trick that only serves the interests of the major media organisations. As the British comedian turned Hollywood actor and Hacked Off frontman Steve Coogan put it, ‘Press freedom is a lie, peddled by proprietors and editors who only care about profit!’. The former funnyman was not joking. If only those heroes of history who had fought and suffered for press freedom could have had access to the wisdom of Coogan/Alan Partridge, they could have saved themselves a lot of trouble. Who would want to be locked up or hanged, drawn and quartered for the sake of ‘a lie’?

The power that a few large entities can exercise over much of the established Anglo-American media is a longstanding problem, which is likely to remain until we all become billionaires or the billionaires all become socialists. It will not be improved by encouraging the state to encroach further upon the freedom of the press and the media. Indeed, it is an argument for demanding that the media be made more open and free, not less.

Freedom of speech and of the press are not only inseparable. They are also indivisible liberties, that we defend for all or none at all. You cannot start tampering with it for one group – even if the group is press barons or PR executives – and expect it to remain intact for everybody else. Once the bulwark has been breached and the cultural support for the principle of freedom is compromised, everything is called into question. And once freedom of speech and of the press is openly called into question it ceases to be a universal right and becomes a privilege to be cherry-picked.

This is not a zero-sum game, where you somehow have to decrease the rights of others in order to increase your own. Freedom of expression is not a negotiable commodity that can somehow be ‘redistributed’ away from the rich and powerful towards the rest. To infringe on the right to free speech of others can only risk undermining your own capacity to exercise it. Those who fought for freedom of the speech and of the press through history demanded the extension of those rights to the lowest and ‘the meanest’ in society, not their removal from others.

For all of its anti-elitist posturing, the current to curb press freedom is at root often a coded attack on the masses who are supposedly ‘brainwashed’ by the mass media. We are far better off defending and extending press freedom, using the new opportunities provided by web publishing, to win a bigger audience for an alternative media.

No doubt there are many imperfections with the press and the wider media today. But history suggests there is always one thing worse than a free press, and that is its opposite. It is worth remembering that nowhere in the world is the problem that the media is somehow ‘too free’. It is high time that the forgotten First Amendment freedom came back into fashion.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by Harper Collins. (Order this book from Amazon(USA) and Amazon(UK).)

Mick will be giving the Battle of Ideas 2015 welcome address: ‘Je suis…what? Free speech after Charlie Hebdo’ on 17 October. Get your tickets here.

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.