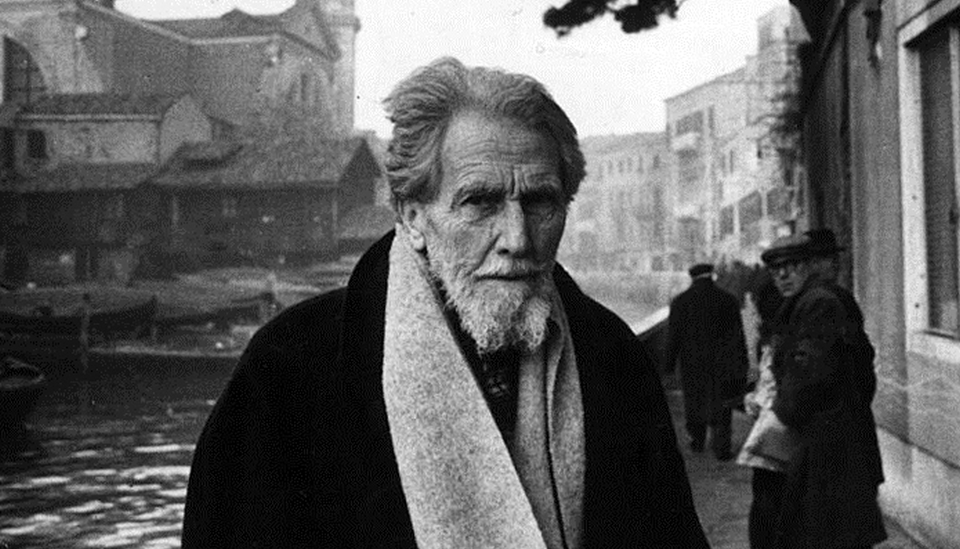

Pound: poet and political prisoner

A new biography shows us just how brilliant, and dangerous, Ezra Pound was.

In 1945 Ezra Pound faced the death penalty for the crime of treason. For a poet who had declared that there were only ‘a few hundred people… capable of recognising what I am about’, the matter of being understood (and misunderstood) had become a matter of life and death. A grand three-volume biography by A David Moody, the final volume of which is published this month, traces Pound’s path from the courthouse in Washington DC.

Ezra Loomis Pound was born in Idaho in 1885. As soon as Pound arrived in London from the US (in 1908), the young firebrand wanted to demolish the polite conventions of Victorian verse. His poems were modern in form but not in content. He used ancient languages and mythic allegories to address pressing matters such as governance and justice. His epic 50-year suite The Cantos runs to over 800 pages of verse in a mixture of English, Medieval Provencal, Italian, Latin and Mandarin. Through its very obscurity, Pound’s poetry offered a radical new direction. His journal Blast advocated Vorticism (a British variant of Futurism); behind the scenes, Pound arranged grants for indigent modernist artists such as James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis, while not being any better off than they were. Hemingway, Eliot and Yeats (among others) considered Pound an invaluable critic. They asked him to edit their writing and consented to the drastic changes he suggested.

His abrasiveness became a trademark. In one announcement, relating to one of the other journals he edited, he declared:

‘Exile will appear three times per annum until I get bored of producing it. It will contain matters of interest to me personally, and is unlikely to appeal to any save those disgusted with the present state of letters in England…’

After a spell in Paris, Pound arrived in Italy, where he settled in Rapallo in 1924. Moody describes how Pound’s poetry and politics converged in Mussolini’s Italy. Pound began to fixate on economics and banking as the root of war and inequality. He wrote numerous cantos distilling John Quincy Adams’s views on government, Jeffersonian economics and nineteenth-century banking theory. Sales of successive volumes of The Cantos slumped dramatically. Even his few dedicated readers admitted that his poetry needed extensive commentary and translation to be intelligible.

Pound, along with many Italians, saw Mussolini as a strong stable alternative to encroaching communism and unregulated capitalism. In the face of widespread poverty and unemployment during the Great Depression, fascism (especially in its Italian form) seemed a beneficent third way. Anti-Semitism did not play a role in Italian fascist policy until 1938, under the direction of Nazi Germany.

Moody records Pound’s campaign of hectic letter- and essay-writing. He assailed US senators and committees with directives on banking regulation and taxation. He even had an audience with Il Duce. International usury became an obsession for him. Many of Pound’s anti-Semitic statements derive from his conflation of his hatred of capital exploitation with casual assumptions about Jewish control of world finances. Taking a provocative stand on artistic matters had been Pound’s stock-in-trade for decades, and he failed to see that in wartime Europe race-baiting was a matter of life and death.

During the Second World War, Pound gave a series of radio talks in favour of the fascist government. The authorities wanted talk of cultural Enlightenment. What they got were lectures on economic theory laced with anti-Semitism, which apparently baffled listeners. Pound’s writings and broadcasts through fascist-controlled channels were not fascist propaganda, but Pound’s own blend of propaganda, ridicule, invective and poetry, which happened occasionally to align closely to official propaganda. Pound’s rants about The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Jew bankers being behind Roosevelt and Churchill did not reach the American people, but they were heard by Allied intelligence services and they were taking notes.

The US Constitution defines treason as giving ‘aid and comfort’ to the enemy in time of war. It is hard to see how much aid or comfort Pound’s rambling diatribes would have given Italy, but Pound was a US citizen, and as soon as he fell into the hands of the US army he was detained. However, conviction for treason requires two eye-witness statements. No one actually saw Pound writing newspaper articles, and radio technicians who worked on his broadcasts did not speak English, so could not testify as to what Pound had actually said. Much of the material the prosecution wanted to present was irrelevant and inflammatory.

The prosecution’s case was so flawed that a trial would very likely have resulted in a verdict of not guilty. Yet Pound’s court-appointed lawyer pled insanity without consulting his client. An exhausted 60-year-old man, of strong and eccentric opinions, had effectively been manoeuvred by his own legal team into an implicit plea of guilty to an unprovable charge of treason. Pound was declared insane and imprisoned in St Elizabeths Hospital for the Insane, Washington DC. There would be no treason trial. Pound was neither convicted nor exonerated of treason and few (including the hospital’s doctors) believed he was actually insane. Yet he languished in legal and moral limbo for over 12 years, confined to a mental asylum, surrounded by the lobotomised, catatonic and senile.

Moody writes: ‘In short, as the psychiatrists had virtually testified in 1946, Pound was guilty of having the wrong ideas, and had to be insane not to see that.’ Effectively imprisoned for supporting fascism and making anti-Semitic statements – neither of which were actual crimes under US law – Pound was a political prisoner in a nation that did not recognise the category of political crime. He could not be pardoned as he had not been convicted of a crime. Over the years, Pound’s captivity became a cause célèbre for lawyers, writers and proponents of free speech, even those who had fought fascism. Increasingly embarrassed, the US government dropped treason charges in 1958, thus effecting his release and allowing his return to Italy. He was declared a ward of his wife, Dorothy, and for the rest of his life Pound was not permitted to have a bank account, to sign contracts, to own property or to make a will. Instead of being condemned to death, Pound was condemned to half-life. He died in Venice in 1972, aged 87.

In Moody’s first two volumes it is hard to like the impetuous provocateur and Jew-baiter; in the last volume it is hard not to feel sympathy for a man broken by his own arrogance and by a miscarriage of justice. One of Moody’s gifts as a biographer is to present the complex strands of Pound’s downfall without ever giving the impression that it was inevitable or even predictable. Moody focuses more on the work than the life, correctly discerning that Pound’s writing has become (in mainstream culture) increasingly less understood and less influential over the years than that of Eliot and Joyce. Moody is an expert on modernist literature and makes an informed guide to both basic themes and complex allusions, confidently explaining many aspects of The Cantos. Moody has succeeded in bringing Pound to life and highlighting the vitality of his poetry. He gives modern readers an understanding of just how brilliant the dangerous, deluded and fascinating Ezra Pound was.

Alexander Adams is a writer and art critic. He writes for Apollo, the Art Newspaper and the Jackdaw. His book On Dead Mountain is published by Golconda Fine Art Books. (Order this book from Pig Ear Press bookshop.)

Ezra Pound: Poet: Volume I – The Young Genius, 1885-1920, by A David Moody, is published by Oxford University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Ezra Pound: Poet: Volume II – The Epic Years, 1921-1931, by A David Moody, is published by Oxford University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Ezra Pound: Poet: Volume III – The Tragic Years 1939-1972, by A David Moody, is published by Oxford University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.