Long-read

The racism racket

Diversity training in the workplace and beyond is worse than useless.

‘Complete and utter crap.’ That’s how Bill Michael, until recently UK chair of global accountancy firm KPMG, described the concept of unconscious bias to his apparently stunned staff. ‘There is no such thing as unconscious bias’, he elaborated. ‘I don’t buy it. Because after every single unconscious-bias training that has ever been done, nothing’s ever improved.’ As is the custom nowadays, Michael issued a public apology before tendering his resignation. This is a shame because his comments were not that far wide of the mark. As I explore in a new report for Civitas, the anti-racism training industry does little to improve outcomes for BAME people and, worse, breathes new life back into racial thinking.

A review commissioned by the Government Equalities Office to analyse the effectiveness of unconscious-bias training found that ‘there is currently no evidence that this training changes behaviour in the long term or improves workplace equality in terms of representation of women, ethnic minorities or other minority groups’. The Harvard Business Review likewise notes that ‘even when the training is beneficial, the effects may not last after the programme ends’. Worse still, mounting evidence points to workplace diversity training actually having unintended negative consequences.

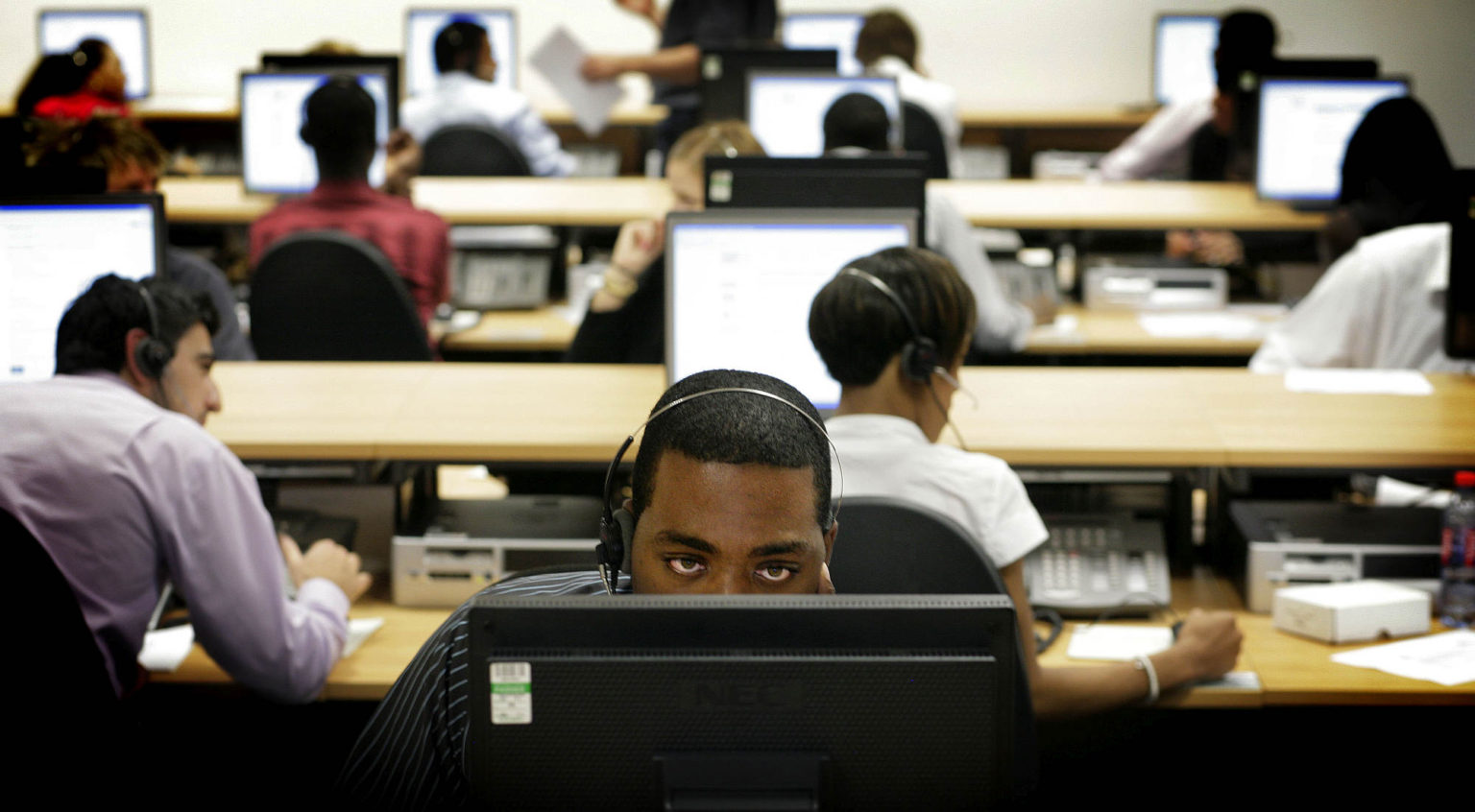

Yet increasing numbers of employers insist their staff undertake anti-racism training. A survey conducted for the Guardian suggests that over 80 per cent of all UK-based companies run training sessions specifically on unconscious bias. Virtually all Fortune 500 companies offer some form of diversity training. The diversity industry has become a global phenomenon, extending its reach to many millions of citizens, with online courses targeting many more. In many schools, universities and workplaces, attendance at anti-racism workshops is mandatory – or effectively mandatory when non-attendance makes your position untenable.

Racism at work

This massive rollout of diversity training is not only taking place without any evidence of its effectiveness — it is also happening at a time when, by all measures, race has never been less of a barrier to advancement in the workplace. Yet the absence of both legal discrimination and explicit prejudice is no hindrance to the rise of the race experts. Binna Kandola, author of Racism at Work, explains:

‘The racism in organisations today is not characterised by hostile abuse and threatening behaviour. It is not overt nor is it obvious. Today racism is subtle and nuanced, detected mostly by the people on the receiving end, but ignored and possibly not even seen by perpetrators and bystanders. Racism today may be more refined, but it harms people’s careers and lives in hugely significant ways.’

According to experts like Binna, racism today is so subtle people need training to perceive it, yet so devastating it does irreparable damage to people’s careers. It exists in indifference, in the things people do not say, yet it is apparently evident in every aspect of our daily lives.

The insistence that racism exists nowhere but is present everywhere, that it can be found within people who ‘do not engage in expressing negative views about minority groups’ but actually ‘believe in greater integration’, and even within individuals who ‘may consistently support policies that promote diversity’, comes directly from critical race theory. Legal equality may have been achieved. And, as Bill Michael found to his cost, expressing a thought that so much as questions contemporary anti-racist orthodoxies can see you out of a job. But the race experts insist they are needed now more than ever. They alone have the power to uncover a ‘legacy of racist ideas, actions and imagery which lives on publicly in stereotypes – and privately in our unconscious minds’ (2).

Unconscious bias

The existence of unconscious bias is a foundational principle of today’s critical race theory-inspired diversity movement. Apparently – and despite us not even being aware of it – our minds harbour all manner of prejudiced thoughts put there by society and culture; through our upbringing, education and our interactions with other people. Proof of these bad thoughts comes out in implicit-association tests (IAT) that track response times when we match certain images, words or phrases with people of different characteristics. Unsurprisingly, the idea that the content of the unconscious mind can be revealed through a rapid-fire computer test is highly contested. The American Psychological Association acknowledged over a decade ago that people’s IAT scores vary from one test to another and are often context-dependent. Yet still the testing continues.

What’s more, the notion that unconscious bias triggers prejudice and discrimination implies there is a direct link between our implicit attitudes and our actions. Yet research has shown that test scores purporting to measure implicit attitudes do not effectively predict actual discriminatory behaviour. Either the contents of our unconscious mind cannot be accurately measured, or people are able to exercise self-control and do not automatically act out the contents of their unconscious.

If unconscious-bias training is simply ineffective then it could be written off as just a harmless waste of time. But it is also making pseudo-scientific claims to be revealing the inner workings of our brain, in the workplace or an educational setting. In the context of racism being one of the biggest sins a person can commit, unconscious-bias training is therefore far more dangerous than mere time-wasting. Implicit-association testing breaches the rights of individuals to freedom of conscience. It holds people to account not for their speech, their actions or even their thoughts – but for impulses they have no control over. Ultimately, unconscious-bias training is divisive; it pushes us to see each other as members of racial groups and, in a bid to make all interactions conscious, it risks preventing the spontaneity and informality that leads to genuine friendship.

Microaggressions

Often, unconscious-bias training is followed by instruction in how to avoid microaggressions. A link is drawn between the two: it is because of our unconscious biases that we unintentionally mistreat people who are different to us. Microaggressions range from mispronouncing someone’s name or asking where they are from, to not making eye contact or not sitting facing a particular colleague in meetings. Diversity trainers teach that the cumulative impact of these slights can have a devastating psychological toll on the individuals targeted.

Training and awareness-raising around microaggressions sensitise BAME people to offence in slights they may otherwise have brushed off or not even noticed. The message is that even the tiniest miscommunication can cause serious harm. The idea that inculcating such extreme sensitivity may be unhelpful is rarely considered. While BAME people are taught to perceive offence, white people learn that not only their speech but their body language may reveal a deeply hidden racism. The only way to counteract this, they are taught, is hyper-vigilance. This further complicates and problematises spontaneous relationships. The risk is that black people come to be viewed – and to perceive of themselves – as especially vulnerable and sensitive to offence. In the workplace, this may lead colleagues to retreat from forging the informal connections that can lead to opportunities for promotion or make managers less likely to offer the feedback that may lead to better performance.

Allyship

Active-bystander or allyship training is the latest fad of the race experts. Unlike unconscious-bias training, which focuses on the unwitting perpetrators of racism, or microaggression workshops, which often focus on the feelings of the victims, active-bystander training considers the role of witnesses to racism. The starting point is that, in failing to act or speak out, witnesses compound the pain inflicted by the original act. Active-bystander training aims to give people the skills deemed necessary to challenge unacceptable behaviours. Specific skills taught include: overcoming fear and paralysis in challenging situations; using the right words and expressions when challenging behaviours; and tackling ‘micro-inequities’, including eye-rolling, sighing, constant interruptions and unconscious bias.

Again there is a huge disparity between behaviour – eye-rolling, sighing – and assumed emotional response: ‘fear and paralysis.’ Through training, people are taught that this reaction is proportionate but, far from being normal, living and working with this degree of sensitivity is itself paralysing. Allyship training is yet another intervention that racialises workplaces and reinforces the notion that everyday interactions may be acts of aggression when carried out by white people and leave people of colour suffering irreparable harm. Worse still, active-bystander training may infantilise BAME people by institutionalising an expectation that they need others to speak up on their behalf.

Counting the costs

Diversity training is a massive industry. But not only does it make little difference to either social equality or workplace relations — it may actually make things worse. Yet despite this, being an expert anti-racist is a highly lucrative business. Successful entrepreneurs like Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X Kendi in the US, and Reni Eddo-Lodge and Afua Hirsch in the UK, earn vast sums of money through books and workshops. One investigation claims that DiAngelo ‘has likely made over $2million from her book’, but that ‘the speaking circuit is where she is cleaning up… [A] 60-90 minute keynote would run to $30,000, a two-hour workshop $35,000, and a half-day event $40,000.’ It goes on to note: ‘Ibram X Kendi, whose book has jockeyed with DiAngelo’s on the bestseller list, charges $150 for tickets to public events and $25,000 for a one-hour presentation… Former Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates has charged between $30,000 and $40,000 for public lectures.’

Sitting below these elite hustlers come myriad academics, experts and workplace trainers who make money from race. For employers, the costs of diversity training go far beyond simply paying for a guest lecturer. They also include the wages of staff directed to spend time in workshops rather than focusing on generating revenue. So why are businesses queuing up to spend all this money? No doubt many well-meaning bosses genuinely believe diversity training will bring positive outcomes or assume that in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests they must be seen to be doing something. But the specific nature of critical race theory-inspired training, in bringing together identity politics and therapeutic practice, also holds significant benefits for employers.

Identity politics meets therapy

Critical race theory lends academic legitimacy to the race experts and provides a theoretical basis for the content of their literature and workshops. Their practice, on the other hand, draws from techniques that originate within therapy and counselling. The non-judgemental starting point of diversity training is that ‘we all have unconscious bias’ and the very fact that this bias is unconscious means we are relieved of all responsibility.

Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn argues that from the emergence of sensitivity training in the 1940s, through to encounter groups in the 1960s, the ritualised practices that now epitomise the diversity industry ‘cannot be understood apart from the culture of therapy’ (3). She suggests that, in the 1960s, ‘psychotherapeutic techniques became widely accepted as appropriate for an ever broadening range of everyday issues or “life problems”’, based on ideas that had been developed in the decades beforehand. Race relations comprised one such life problem considered resolvable through therapeutic practices mediated by experts who offered enlightenment through training.

The therapeutic practice that forms the basis for most diversity training means familiar patterns are observed irrespective of the specific focus of the workshop. In order to introduce new ways of thinking and behaving towards others, people must first be made self-conscious about their existing relationships. People are taught to see themselves not as individuals, nor as friends and colleagues with interests in common, but as representatives of racial groups. Then, with spontaneity replaced by self-consciousness, attention is drawn to the differences between groups. Sometimes this process involves participants being asked to verbalise stereotypes they have encountered – even if they do not, nor ever have, accepted or reinforced those stereotypes themselves.

Next, participants are informed that there are racialised differences in the emotional responses people demonstrate when confronted with such stereotypes: black anger and white guilt. And then finally, trainers lead participants through a process of acceptance and validation of these emotional responses. Lasch-Quinn argues that black anger and white guilt are validated on the assumption that no individual is responsible for their feelings: it is society that has created stereotypes and fuels prejudice. When it is accepted that stereotypes, not individuals, are responsible for racism, then the trainer can offer instruction in approved interracial etiquette that focuses upon acknowledging and managing emotional responses in an acceptable way.

When considered in this way, expecting diversity training to reduce instances of racism may be to miss the point. The aim, it seems, is not a solution to racism but a reconciliation to its existence and a commitment to seeking it out where it remains hidden, thereby exposing yet more problems to be resolved through further rounds of training. All criticisms of this process are explained as ‘white fragility’ and serve as evidence of the need for yet more training. The sole aim of the diversity industry thus appears to be its own self-perpetuation. Each new iteration provides additional moral weight and, of course, revenue, for the professional anti-racists.

The benefits, not just for employers but for school leaders and university managers, of fuelling this industry are numerous. Diversity training breaks down any sense of solidarity between people and makes the formation of spontaneous bonds far less likely to occur. Individuals learn to be vigilant of their own behaviour, to appraise the actions of others and report indiscretions to managers far more effectively than any clipboard-wielding time and motion monitor. Through unconscious-bias training, employers gain access not just to our labour, or even our intellect, but to our emotions. They are then able to position themselves as therapeutic arbiters not just in our relationships with others but also, more significantly, in our very sense of who we are. The mandatory nature of much diversity training means schools, universities and the workplace are transformed from sites of education or labour into places for the inculcation of a particular ideological approach. Critical race theory – truly the gift that keeps on giving – means that if you take part in training you will discover you are racist; but refusal to participate is also a sign of your racism.

Employers not only have free rein to intervene in workplace relationships but they can also take the moral high ground while doing so. Whether through conviction, calculation or cowardice, the diversity-training juggernaut rolls ever onwards, to the detriment of all but a tiny elite.

Joanna Williams is the author of Rethinking Race: A critique of contemporary anti-racism programmes, published by Civitas.

(1) Racism at Work, by B Kandola, Pearn Kandola Publishing, 2018

(2) Racism at Work, by B Kandola, Pearn Kandola Publishing, 2018

(3) Race Experts, by E Lasch-Quinn, Rowman and Littlefield, 2001

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.