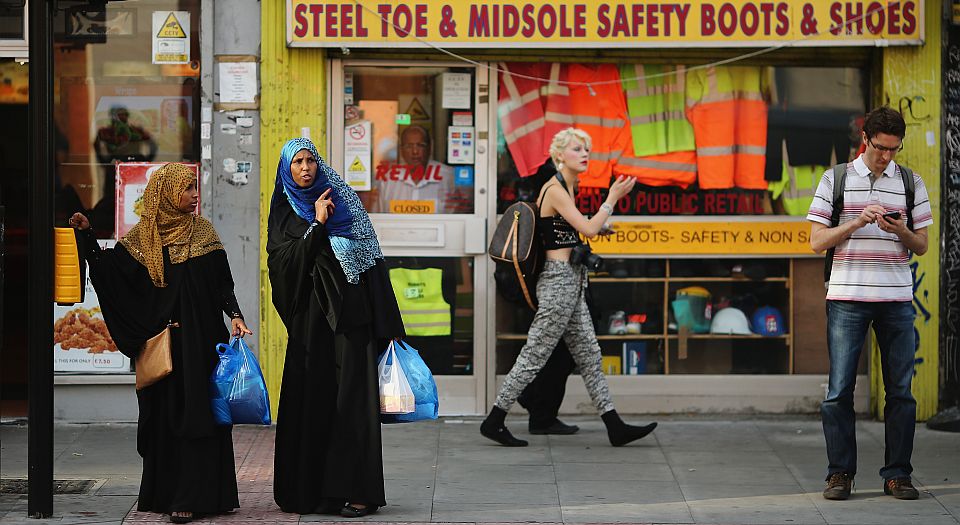

Multiculturalism has failed

We need a new politics devoted to bringing people together.

Over the years more and more mainstream European politicians have woken up to the failures of multiculturalism in their respective countries.

Back in 2010, at a meeting with young members of her Christian Democratic Union party, German chancellor Angela Merkel conceded that Germany’s multicultural approach – known as multikulti – had utterly failed. In Germany, as in so many other European countries, culturally disparate communities are living side by side, but with minimal cross-group interaction and meaningful contact.

Many of Merkel’s colleagues, such as Horst Seehofer, have long declared that the concept of Leitkultur (a ‘leading German culture’) and a more regimented immigration system are needed to create a more cohesive Germany.

But although Merkel has had the courage at points to talk about the problems of multiculturalism, her actions more recently have only exacerbated them, and undermined her reputation as a steady, sensible and responsible leader in the process.

Her decision in 2015 to allow in approximately one million refugees from unstable Muslim-majority countries, such as Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, placed considerable strain on Germany’s social fabric. This decision was all the more mind-boggling in light of the fact that Germany had already struggled to integrate migrants of Turkish Muslim origin – and even their German-born children.

When it comes to the issue of multiculturalism, many countries across Europe are in need of robust political leadership. We need leaders who acknowledge the drawbacks of multiculturalism and are willing to confront deeply concerning cultural practices and norms within migrant communities. On this front, there are reasons to be hopeful.

Under the thoughtful leadership of Mette Frederiksen, the Danish Social Democrats are seeking to create a national culture based on shared identity, common purpose and mutual obligations. The party has also adopted a mature approach to public concerns over immigration and social cohesion. The Danish premier has openly criticised problematic attitudes within her Danish Muslim communities – including a lack of respect for Denmark’s judicial system and embedded forms of patriarchal coercion.

It is not racist to have reservations about multiculturalism. Nor is it racist to be concerned about the social impact of allowing into your country a great number of people from unstable countries, in which prevailing cultural and legal norms vastly differ from those of your own. You can be comfortable with racial diversity and simultaneously anxious about religio-cultural diversity. This is by no means a contradictory position.

We here in Britain need to grasp this issue. Multiculturalism here has led to a similarly divided society, and we desperately need to foster more integration. But to do so requires us to pose the question: what are we asking migrants to ‘integrate’ into? When we ask people to adopt ‘British values’, what are we referring to? Because all is not well within mainstream British culture.

The UK has established itself as a world leader in family breakdown. We have among the highest rates of binge-drinking in the world. We have an unhealthy obsession with celebrity ‘icons’. The level of loneliness among the elderly is not only a social scourge, but also a national embarrassment. These features of modern British society and culture are not desirable by any stretch of the imagination.

What the UK requires, therefore, is moral and political leadership. We need someone brave enough to call out problematic behaviours and attitudes in society – both in the general public and less-integrated migrant communities. And we need to carve out a set of common values.

Multiculturalism is ultimately doomed to failure. In championing difference over cohesion, it fails to provide a central moral and cultural standard. Without this shared social framework, it is nigh-on impossible to cultivate the bonds of trust and mutual regard needed to tie together a multi-ethnic, religiously diverse society. This should be a particular concern for those who are supportive of a comprehensive welfare state, which can only be properly sustained by a high-trust, cohesive society.

The answer to all this is a brand of patriotism that is inclusive, community-spirited and family-oriented: one that understands the human desire for neighbourliness; that celebrates hard work and encourages social responsibility; that emphasises respect for the British rule of law; and that recognises the socially harmful effects of ‘parallel societies’, which particularly blight post-industrial northern towns.

Brexit could well be the catalyst for the social renewal that this country so desperately needs. As a self-governing nation state, we could develop a sensible immigration system that prioritises individuals with English-language skills and those from Commonwealth nations with similar political and legal systems. A post-Brexit Britain could strive to develop a model of cohesion that firmly rejects both an ethno-centric understanding of nationhood and the grievance narratives peddled by the identitarian left.

We should embrace a politics of mutuality, reciprocity and responsibility, and consign multiculturalism to the dustbin of history.

Rakib Ehsan is a spiked columnist and a research fellow at the Henry Jackson Society. Follow him on twitter: @rakibehsan

Picture by: Getty

Clarification: an earlier version of this article stated that Angela Merkel had discussed multiculturalism at a ‘recent’ meeting. This has now been changed to clarify that the meeting referred to was in 2010.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.