What Marty Crane can teach us

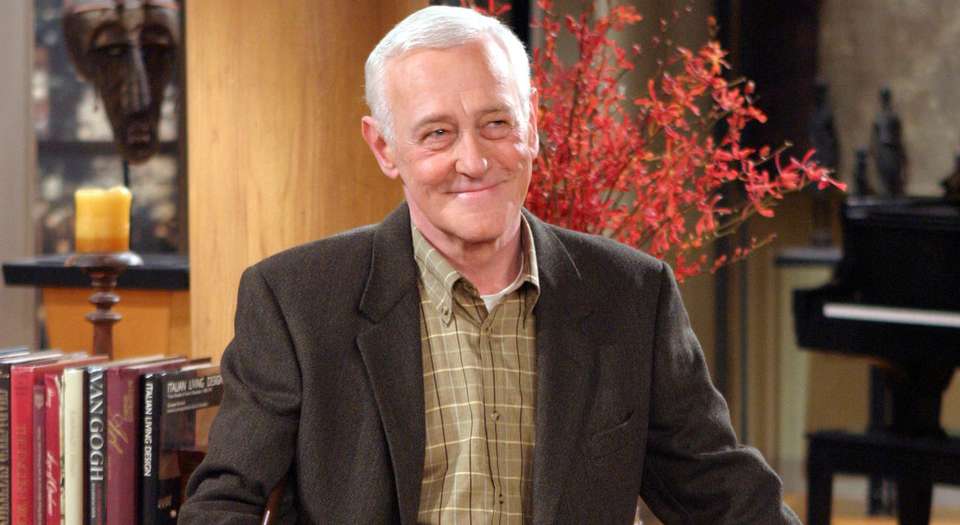

John Mahoney’s character pre-empted today’s culture clash.

There will be many of us who will lament the death of John Mahoney, the actor best known for playing Marty Crane, the cranky father in Frasier. Much of the best comedy is based upon generational conflict and misunderstanding (consider Steptoe and Son, Till Death Us Do Part or Absolutely Fabulous), and Frasier was premised on this classic trope.

It placed Marty Crane, a plain-spoken, beer-drinking curmudgeon, as the unwilling lodger of his pretentious son Frasier – Seattle’s cerebral and celebrated radio psychotherapist. They had practically nothing in common. The only thing that the two genuinely loved and shared was Marty’s wife and Frasier’s mother, who was no more.

Every episode of Frasier had as its foundation this rift between Marty’s grounded, blue-collar ways and Frasier’s lofty ambitions and high-falutin’ thinking. While the radio dj may have been adept at dispensing sound advice on the airwaves, he was a luckless nincompoop in real life. His social climbing and his libido led him hopelessly astray. In most episodes it was up to Marty to bring Frasier back down to earth.

The gulf between this fictional father and son seems even more pertinent in today’s reality than it was when Frasier was at its peak 20 years ago. This decade will be remembered as one of a clash between the ordinary man and the elites, between your Brexiteers and Trump voters from ‘left-behind Britain’ and the American rust-belt on the one side, and the wealthy, cosmopolitan, liberal class on the other. Between people from Somewhere and people from Anywhere, as David Goodhart has put it. While Marty was a classic everyman for whom familiarity was the spice of life, his son found working-class culture alien. Frasier Crane was that kind of American who would have used the phrase ‘fly-over states’.

This decade’s clash between the Anywhere and Somewhere people has been bitter and nasty. It has brought friends and families to blows and caused them to fall out. Families will quarrel, as Marty and Frasier did to marvellous effect, but they can make up too. This was the genius of Frasier. Despite their irreconcilable personal differences – beer versus wine, football versus opera – they eventually came to recognise each other as human beings: as real, living, breathing, fallible human beings, who bled and cried and hurt, but who just happened to see the world differently.

I think there’s a lesson here. Liberal democracy is based upon the premise that we must live with people we find intolerable, even when they have got the proverbial garish, frayed reclinable chair and chummy dog. In our hyper-sensitive, censorious and intolerant times, it’s too easy to forget this.

The problem with equality

The celebration of the centenary of some women being granted the vote in Britain has been accompanied by a litany of cries that ‘the fight for equality has yet to be won’. I quote, for example, Ruth Davidson, leader of the Scottish Conservative Party: ‘On equal pay, on property and company ownership, on admission to higher education, on maternity protections, on military service, on spousal rights… we still see women more likely to advance slower than men.’

Whenever I hear the word ‘equality’, alarm bells start ringing. This is not because I’m against anyone being given a fair chance in life, but because of the way the word is used today. Agitators for ‘equality’ always seek equality of outcome. This always ensures interfering, bean-counting, ethnic- and gender-tokenism, and the ultimate promotion of the mediocre, which causes great resentment among everyone else – all in the sacred, anal pursuit of achieving some statistical parity.

Equality and liberty are not two goals to be pursued at the same time. They are mutually antagonistic. The more you have of one, the less you can enjoy the other. The only way a society can achieve full equality of outcome is for the state to intervene and force it to be so, by taking from some and giving to others. The only way a society can become truly free is to let people go about their business, and as a consequence let some become more unequal than others.

Maybe women will one day be equal. Most of us would welcome this. But forcing people to be equal? That’s when our problems would really start.

Who cares what colour Cheddar Man was?

I don’t see anything remotely noteworthy about the fact that the first human inhabitants of Britain were black. But clearly other people have been very excited by the news.

‘Cheddar Man: confounding British stereotypes’, declared the front page of the Daily Telegraph on Wednesday, with an accompanying photograph of what is imagined to be a prehistoric Briton. ‘A facial reconstruction has been based on the skull of Britain’s oldest skeleton, the 10,000-year-old Cheddar Man, following research at the Natural History Museum that suggests the first inhabitants of the British Isles may have had dark skin.’

Others were positively delirious. Steven Clarke, director of a Channel 4 documentary on the revelation, said: ‘You go back quite far and discover that everything’s in flux, everything changes… There is a national debate, and a debate about our relationship with Europe. All those things are still in the mix. It speaks to us now.’

Throw away your history books, everybody. Your world has been turned upside down. This changes everything. As they concluded on Twitter: ‘The first Briton was black. HA! HA! BREXIT IS WRONG!’

Except it hasn’t changed anything. If you consult your history books, you will find out that people in the past who lived in your country usually didn’t look like you. They didn’t sound like you or have the same beliefs or politics as you. Britain has for thousands of years been a place where different peoples have lived, fought and intermingled. This news about Cheddar Man being black is about as exciting as discovering that before the Anglo-Saxons there were the Celts. And that before the Celts, we all lived in Africa. And that before that, our ancestors lived in the sea. And before that the Big Bang.

I mean, so what? What matters is who we are now as Britons. If we are to draw any conclusions, as Mr Clarke insists, I would agree that when it comes to Europe, everything is indeed ‘in flux’. We don’t have to stick with the decrepit status quo. The future is ours to change.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.