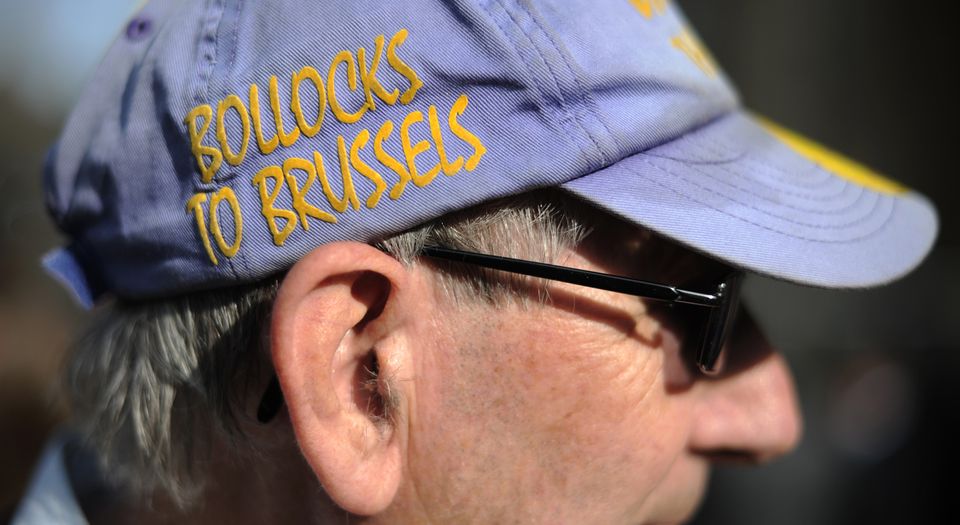

spiked’s person of the year: the unflinching Brexiteer

Brexit voters have reminded the world what conviction looks like.

We live in age of cave-ins. Recanting is all the rage. Go off-message, be off-colour, wonder out loud if men really can become women, crack a joke better suited to 1977 than 2017, and a Twitterstorm will form around you. A thousand unforgiving fingers will jab in your face. You’ll be warned to backtrack, and apologise. And people do, all the time. Celebs, politicians, journalists who make clumsy passes at women, Princess Michael with her ‘racist brooch’: every day someone gives in to the dogmatists and offers up their dignity in return for forgiveness.

Which makes the unflinching Brexiteer, those millions who have refused to budge on their convictions in the face of the most ferocious chattering-class demand for political repentance in living memory, so peculiar. And so worthy of celebration.

The steadfast Brexit voter, that vast body of men and women who are standing by what they believe in, is spiked’s person of the year. For the simple reason that they have reminded us what conviction looks like. Of course they’re denounced as extremists — or ‘Brextremists’. That is only to be expected at a time of Third Way political blandness, when strong beliefs are viewed with suspicion and it’s a virtue to be a bean-counting bore who tries to win voters over with pie charts rather than passion. In the land of the technocrat, the man with conviction is viewed as a freak.

Such slurs, such wrongheaded denunciations of thoughtful, feeling voters as extremists, tell us far more about the flatness of mainstream politics today, about the political elite’s replacement of ideals with a deathly managerialism, than they do about any weirdness among the Brexit masses.

So when, in August, a YouGov survey found that 61 per cent of Leave voters thought ‘significant damage to the British economy’ was a ‘price worth paying’ for Brexit, and that 39 per cent thought personal hardship was a price worth paying, there was astonishment, alarm even, among the political and media sets. They have so forgotten what politics look like, they are so estranged from the modern era of belief and struggle that gifted them the freedoms and comforts they enjoy, they are so enamoured with the stiff, suited, ‘expert’-led anti-politics of the Brussels oligarchy, that they view sacrifice in the name of an ideal as tantamount to insanity.

The unflinching Brexiteer mystifies and offends them because he runs so counter to the spirit, or anti-spirit, of the age. He is the grit in the machine of technocracy, the unwanted reminder of the old era of belief. So the media set is forever on the hunt for evidence of ‘Regrexit’, for signs that Those People are coming to their senses, backtracking, recanting. They scour the land for the rarely spotted creatures who have changed their minds and splash them across the newspapers. ‘Here! Look! They’re turning!’ But they are deluding themselves, and they know they are, for poll after poll suggests Brexit voters aren’t shifting in any significant way.

There are fluctuations, of course, but they’re minor. One poll found that three per cent of Leavers regret their vote — but it found four per cent of Remainers regret theirs. The most recent YouGov poll found 52 per cent of the public think we should get on with Brexit and only 14 per cent think it should be abandoned completely. And we should never discount the possibility that, in the face of unprecedented media fury and political-class disdain for what they did, some Brexiteers will tell pollsters that they regret their vote because they think it’s what they want to hear. As a Washington Post writer put it, ‘It’s not hard to imagine that some Leave voters, faced with a global media that deems their decision unimaginable and foolish, might tell a reporter that they regret their vote. Some of these people may mean it — some may not.’

In the round, Brexit voters are sticking by their vote. They still want the thing — the break with Brussels, the re-democratisation of British political life — that they voted for in their teeming, historic millions 18 months ago. And this is incredible.

It’s incredible because no vote in living British memory has been so demonised, so blamed for every social, political and moral ill, as the Brexit vote has been. No section of the electorate has been so insulted, so libelled, so written off as destructive and dangerous, as the Brexit electorate has been. No recent political decision has been so thoroughly judged by the political class to be illegitimate and undesirable, so wicked that the intervention of the law or the Lords or some other caste of expert is required to temper it, as the the Brexit decision has been. And yet Brexit voters remain firm. They have refused to do what you’re meant to do these days — make a display of contrition under pressure and promise never again to upset those who know better than us.

This unflinchingness suggests something significant is at play in British public life, albeit invisibly, far from the political mainstream — and that is a resourcefulness, a moral and political resourcefulness, among sections of the electorate. Whole groups of people, entire communities, 17.4million people no less, have somehow managed to insulate themselves against both the outlook of the new technocratic elite and the relentless pressure to give up on Brexit. Despite the decay of old institutions, the withering of old solidarities, the ravaging of community life by successive governments, people have somehow developed the means to withstand the project and the pressures of the new oligarchy.

How else do we explain the commitment to Brexit? Individuals alone would find it very difficult to stand against the vast bile and stress being heaped upon them daily by the anti-Brexit political and media class; there must be a togetherness, a network of sorts, a solidarity of outsiders, which enables Brexiteers to remain committed to their ideals.

Somewhere in this there is the potential basis of a new politics. All the brilliant, important things about politics that have been notable by their absence in recent decades — conviction, a commitment to popular democracy, a belief in change, a feeling that public life is for the public — are there in Brexit, and even more importantly in the seemingly unbreakable Brexit spirit. Against the dogmatism of the new elites, against the misplaced certitude of this self-styled expert class who arrogantly assume public life is theirs to manage rather than ours to shape, Brexiteers have said, ‘No, there’s another way’, and they aren’t changing their minds on that. It is the most positive political cry anywhere in the West right now.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked. Find him on Instagram @burntoakboy

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.