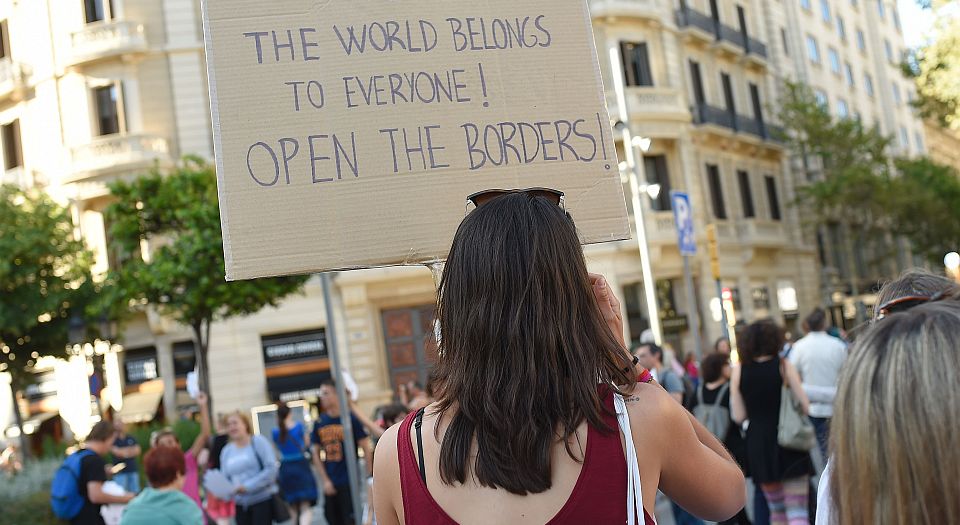

How ‘open borders’ became an illiberal cry

The West’s sanctification of diversity is segmenting society.

Since the 20th century, one of the key arguments made against immigration is that it has a corrosive cultural impact on community life. Anti-immigration groups mobilised against immigration on the basis that it represented a threat to their nation’s way of life. Advocates for immigration, meanwhile, rejected this analysis. They insisted that claims about ‘cultural disruption’ were exaggerated. In response to anti-immigration rhetoric, they said immigration did not fundamentally alter the character of host societies. Moreover, they said, if they were treated well, then newly arrived migrants would swiftly adapt to, and embrace, their new nation’s culture.

More recently, however, the terms of this debate have changed. Both sides now acknowledge that the impact of immigration on society is likely to be disruptive. The debate now is over whether the disruption caused by immigration, and its social and cultural consequences, is positive or negative. Opponents of immigration only see immigration’s negative impacts on society. And while supporters of immigration now accept that immigration will change the character of a society, they insist that this transformation is, on balance, a good thing. From this standpoint, immigration comes to be considered as a positive and welcome instrument of social change.

Today, arguments in favour of mass migration don’t focus on the virtues of free movement; they focus on what are seen as the positive effects of mass migration on a host society. These positive effects are frequently communicated in the language of economics. But, increasingly, immigration is valued on the basis that it has a transformative effect on national culture, too. The use of immigration as an instrument of social engineering could be glimpsed in a statement made by the European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker last week. He declared that ‘borders are the worst invention ever made by politicians’. He coupled his condemnation of borders with a call to support migrants. But this wasn’t simply about showing solidarity with migrants. No, he was communicating a broader hostility towards the idea of the nation state and those who support it. ‘We have to fight against nationalism’, he said, ‘[and] block the avenue of populists’.

Juncker’s animosity towards borders is inspired less by a love of migrants than by a loathing of the nation state. The EU immigration policy that has evolved under his presidency has focused on depriving European nations of their right to determine their own approach to immigration. It involves imposing quotas on member states and depriving national governments of the authority to control the flow of migrants into their society. It is about diluting the nation state.

Open borders

Historically, progressive supporters of open borders were motivated by a desire to defend the human aspiration for freedom of movement and mobility. In the current era, however, borders are not so much seen as obstacles to the free movement of people, but as representations of the nation state and national cultures, and therefore as bad. Rather than being moved by the old, liberal conception of freedom of movement, it is disdain for national sovereignty and the authority of the nation state that inspires Juncker and other pro-EU advocates to celebrate migration.

Of course, in public debates the anti-borders lobby rarely argues explicitly for immigration as a means of social engineering. Instead, it couches its arguments in the language of economic benefits. The most coherent, eloquent argument for immigration as a means of marginalising national culture was made by the German philosopher, Jürgen Habermas, through his concept of ‘constitutional patriotism’.

This idea of constitutional patriotism was developed as a counter to the idea of the nation. Haunted by the legacy of Nazi Germany, Habermas wanted to create a new German political culture — one that would be open to the influence and experience of new migrants. Through accommodating itself to the new reality of migration, Germany could divest itself of its nationalistic heritage, he wrote. The main purpose of constitutional patriotism was to challenge the privileged status of German culture through opening it up to other influences.

For Habermas, constitutional patriotism provides an alternative to ethnically based nationalism. It seeks to create a common civic political culture based on the recognition and celebration of different ways of life. His emphasis on the construction of a civic political culture is the liberal side of Habermas’ argument. However, for Habermas, the creation of this civic political culture serves an illiberal purpose: transforming public life through eroding the status and authority of the national culture. He presents Germany as fundamentally a migrant society: its national culture, therefore, should not enjoy any privileges because, according to Habermas, a liberal society should not discriminate against any subculture.

Habermas is right to oppose political or legal discrimination against subcultures. But the attempt to empty national culture of its unique status would, if successful, decouple society from its traditions and legacy. It would create a technocratic society, where political culture comes to be disconnected from any sense of nation, even of the nation as a physical, geographical entity. Indeed, Habermas explicitly calls into question the right of a majority national culture to determine the values of citizens, because we have to make it ‘possible for different cultural, ethnic and religious forms of life to coexist and interact on equal terms within the same political community’ (1).

Although the concept of constitutional patriotism arose from Germany’s troubled relationship with its past, it now resonates widely with the modern West’s celebration of the idea of diversity. For significant sections of the Western elite, diversity has become a value in its own right — and this is largely down to their sense of estrangement from the values and historical institutions of their own societies. So the ideal of diversity is not simply about appreciating cultural difference — rather it is held up as being inherently superior to the very traditions of a society.

In earlier times, advocates of change promoted political ideologies, such as liberalism, communism or socialism, in order to bring about desired objectives. Today, at a time when social engineering has displaced ideology, many see diversity as the motor of change. US vice-president Joe Biden expressed this sentiment last year, when he welcomed the Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff to Washington. He said that ‘those of us of European stock’ will be a minority by 2017, adding ‘that’s a good thing’. But why should a change in the ethnic or cultural composition of a society be a ‘good thing’, or a ‘bad thing’, for that matter?

In a previous speech, in Morocco in December 2014, Biden said the impending minority status of Americans of European stock would make America a stronger nation. ‘The secret that people don’t know is our diversity is the reason for our incredible strength’, he said. Forget America’s democracy, Constitution, liberal ethos, creativity or entrepreneurship – apparently the real secret of America’s strength is its diversity! Of course, a society open to immigration is likely to benefit from the mixing of cultures and ideas. But when diversity is transformed into a standalone medium for change, it can become a political weapon, and be used to bypass the national will. For Juncker, weakening national borders is beneficial because it serves his project of European federalism. Diversity is the antidote to nationalism.

In the British context, immigration is sometimes argued for on the basis that it will turn Britain into a more enlightened, less British, society. Some of the supporters of New Labour’s policy of relaxing immigration controls were enthusiastic about it precisely because they understood it would have a corrosive effect on Old Britain. As recalled by former New Labour adviser Andrew Neather, one of the arguments for relaxing border controls was that it would make Britain more multicultural:

‘I remember coming away from some discussions with the clear sense that the policy was intended – even if this wasn’t its main purpose – to rub the right’s nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date. That seemed to me to be a manoeuvre too far.’

No doubt it was a ‘manoeuvre too far’, but the idea of rubbing the ‘right’s nose in diversity’ reflects a now common desire to harness immigration to the project of challenging the traditions of national culture.

The politicisation of diversity

The transformation of open borders from a liberal project into a tool for social engineering should make all tolerant people wary of the rhetoric that surrounds immigration and diversity today. The use of immigration as a tool to weaken national sovereignty is wholly destructive, provoking cultural confusion and uncertainty. An enlightened argument for freedom of movement must also uphold national sovereignty, and recognise the status of the prevailing national culture. Disregarding the special status of national institutions and culture is an invitation to a permanent war of cultures — that is, to real division and tension.

Once diversity becomes politicised and institutionalised as a value in itself, it loses its positive potential for opening society up to new ideas. When diversity is politicised, it inevitably encourages more diversity, to the point where society becomes increasingly segmented along the lines of lifestyles and subcultures. Without some sense of common focus and loyalty, cultural segregation looks set to become the norm in Europe: the end result of the technocratic institutionalisation of diversity above all other values.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, Power of Reading: From Socrates to Twitter, is published by Bloomsbury Continuum. (Order this book from Amazon UK.)

(1) ‘The European Nation State: On the Past and Future of Sovereignty and Citizenship’, by Jurgen Habermas, Public Culture, 10 (2), 1998, p408

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.