Long-read

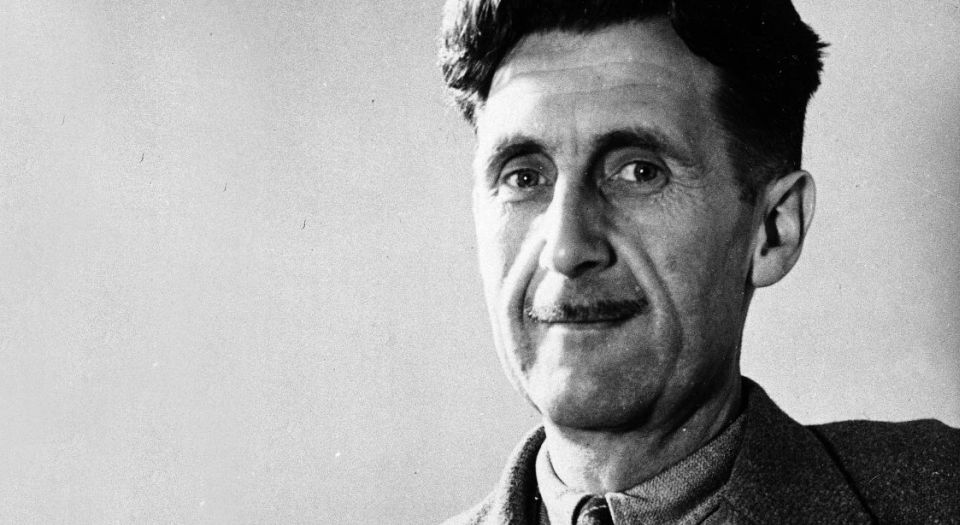

Orwell’s people and the people’s Brexit

Born when only the toffs spoke for England, Orwell devoted his life to giving the people their voice.

On 27 September 1938 Eileen Blair wrote to her sister-in-law Marjorie Dakin saying that her husband George Orwell (Eric Blair) was waiting to hear ‘what he calls the voice of the people’, which ‘he thinks might stop the war’. Right up to the declaration of war a year later and even after that, Orwell went on hoping that the people would speak so that war might be avoided.

In fact, the British people came to the decision that war was unavoidable a year before Orwell and at least six months before its outbreak. Living in Marrakesh, the Blairs were clearly out of touch. While George was writing a pacifistic novel in his shirtsleeves, Eileen was expressing her horror at the Dakin family’s struggles to build an air-raid shelter. ‘It’s fantastic and horrifying that you may all be trying on gas masks at this moment.’

Eileen went on to refer to her husband’s belief in the people as a streak of ‘extraordinary political simplicity’ in him, but where else was he to look? Churchill was no political simpleton and he, too, was trying to find the people in this moment of danger. In the event, once the fighting started in earnest, in a bear-pit called the House of Commons, the people found him.

All Orwell’s writing can be seen as an attempt to listen. This often meant putting his ear to places, Wigan for example, he never really knew. He did know, however, that whole peoples could be misrepresented by their rulers. His first politics had been against the British Empire. Later, he would write about his prep school as a master class in deception. He saw the Soviet Union in the same light and, as everyone knows, Nineteen Eighty-Four is about the systematic misrepresentation of people to the point of extinction.

In 1940, Orwell stopped worrying about peace and waded into the fight. A spate of unashamed celebrations of Englishness followed, including ‘The Art of Donald McGill’ (1940); ‘Boys’ Weeklies’ (1940); ‘My Country Right or Left’ (1940); essays on Dickens (1940), Kipling (1942), and Wodehouse (1945); The Lion and the Unicorn (1941); a composite, The English People, written in 1943 but not published until 1947; Animal Farm (1945), and an essay on liberty, ‘Politics and the English Language’ (1946). His critics might call this propaganda but he would have called it turning up the volume. Born in an age when only the toffs spoke for England, Orwell devoted his life to giving the people their voice and between them, they worked it out. That is what great writers do. They resonate and keep on resonating with those who follow. Orwell stands now as England’s most favoured way of talking about itself.

So, Orwell’s belief in this strange but necessary sovereign force, ‘The People’, was aligned to his own powers of observation and argument. He was a populist in that he pretty much ignored national institutions. He was a writer in that he trusted to his art to make the case for sovereignty. Thus, Orwell doesn’t cite the rules: he points to the lawfulness of the people. He doesn’t orate on inequality: he catches the eye of a young woman unblocking a drain. He doesn’t say capital punishment is contrary to human rights: he puts you on the shoulder of a prisoner making his way to the gallows. He doesn’t write in praise of Internationalism: he shakes hands with a young Italian soldier in Barcelona. At every point, he draws your attention, pulls your sleeve: it’s you who invokes the law, catches the eye, walks the line, grips the hand.

‘As we went out he stepped across the room and gripped my hand very hard… It was as though his spirit and mine had momentarily succeeded in bridging the gulf of language and tradition and meeting in utter intimacy. I hoped he liked me as well as I liked him… One was always making contacts of that kind in Spain.’

(Homage to Catalonia, (1938))

Orwell’s belief in England had first begun in the dark, on his knees at a Yorkshire coal-face. The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) tells the tale of an Old Etonian socialist who went north to look at the unemployed and returned south to look (very hard) at himself. In Spain (Homage to Catalonia (1938)), he found the same qualities of courage and comradeship in the Republican militias that he found in Wigan and Barnsley. Coming Up for Air (1939) reached out to his own class in London and the Thames Valley. The Lion and the Unicorn, written in the darkest hours of 1940, took northern muscle and southern brain and added the astonishing (not to them) discovery that the people were patriotic. What emerged was a folk more than a class who, whatever their observable differences, believed intuitively in their own emotional unity. Not so long ago, Orwell wanted them to be ready to die in defence of their glorious socialist revolution, if they had one. Now they were ready to die in defence of their country, if they had one. Sometimes, in order to be free you have to belong, and for the first time in his life he felt he did.

An Orwell for today?

It is, of course, a really terrible idea (blame the editor) to say anything at all about Brexit and a man who has been dead for 68 years. His situation then was not our situation now.

Anyway, which ‘Orwell’ do we choose? The mildly delinquent schoolboy? The Parisian down and out? The young man of the left, the fighting anarquista, the English patriot or the writer getting ready to die before his time? In a short life there were many Orwells, but one thing is for sure: he never stopped thinking and, in this, he was as hard on himself as on others. As Christopher Hitchens put it, Orwell was a man always taking his own temperature.

As for which ‘Brexit’? Don’t even ask.

In the first place, Orwell never wrote about economics except in the most generalised sense. This is not to say he wasn’t interested in the making of livings. Never rich himself, he kept a meticulous pay book of small sums for huge labour. In Wigan he collected miners’ pay stubs and interviewed families living on unemployment benefit. He tried to imagine life in a one-up, one-down house full of kids. Unlike almost any London journalist who has ever lived or is likely to live, he got close enough to know the difference between a back-to-back and a terrace. But variations on the future performance of a statistical construct called ‘the economy’ according to variations in a statistical speculation called ‘the terms of trade’ would, I fear, have left him cold. He had seen economic orthodoxy get the 1930s completely wrong. He knew that wealth was more than money. Had he lived, no one would have ever called him Spreadsheet George.

It is equally difficult to see Orwell siding with the Federation of British Industries. Whenever he ventured a practical policy, which was rare, he tended to the regulation of markets. The Great Crash of 1929 showed how greedy, and global, capitalism could be. It would have been a great gift to English letters if Orwell had spent a weekend in the company of super-rich hedge-fund managers (‘The Road to Brighton Pier’?) but I think he would have preferred to ride the 6am migrant-worker truck.

Second, it’s a moot point just how democratic the European Union is, but the sight of bureaucrats dealing dossiers late into the Brussels night would not, I think, have touched his soul. Nor would the Commission’s habit of rejecting national referenda until the people said (were deemed to have said) what Brussels wanted them to say. Some Remainers say that democracy is ‘government by explanation’. Others say it is ‘government by process’. Maybe we could have expected some wry comment from the author of ‘Politics and the English Language’ on these meaningless duds. After 60 years and a lot of trying, the EU still cannot relate to the people it represents, not only because all its stories are top-down, but because it has failed to develop the impulse to make it mean more than its parts. Even French President Emmanuel Macron accepts this and wants change. In the meantime: can you name your MEP?

This is not to say that Orwell always found the status quo insupportable. He backed Churchill’s premiership and went on to back Attlee’s government through thick and a lot of thin but, having caught sight of Cameron’s backside on 23 June 2016, it’s hard to see him resisting the invitation to have a kick. Tory mavericks like Johnson and Gove he would have found slightly more interesting (and literary). Corbyn’s ‘constructive ambiguity’, however, surely would have caught the ear of the man who gave us Doublethink.

On the question of peace in our time, Orwell was a realist who saw it fail in 1939 and knew by 1944 that peace in Europe depended first on stopping Germany, second on stopping Russia and third on building a strong eastward-facing alliance. Only then might he have conceded some role for Franco-German collaboration after 1951, although even now neither of those states pay their share of the NATO budget.

That said, Orwell was certainly interested in building a social-democratic Western Europe. He told the New Leader in 1947 that a Socialist United States of Europe might keep Europe out of Russian hands and offer an alternative to American capitalism. Later that year he told Partisan Review that a SUSE was ‘the only worthwhile political objective today’, but went on to say that he didn’t think it would be allowed to be properly democratic, or socialist and, all things considered, he was right.

Orwell did not live to see the European Coal and Steel Community (1951), but his antipathy to the influence of the Roman Catholic Church might have prompted him to look very closely at Monsieurs Schuman, Adenauer and De Gasperi and the Christian Democratic parties as architects of the new European state. Like the Vatican, but unlike the House of Commons, Brussels does not have a sovereign people to worry about. Commissioners are not used to politics. They lay down the doctrine while British prime ministers can hardly hear themselves speak. EU Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier’s ex cathedra pronouncements (‘Since the very beginning, quite naturally, I have been objective’) might have reminded Orwell that the Church was not dead, only living in another body. Cardinal Barnier does not negotiate sin. He explains its logical consequences in the eyes of the Church.

Fourth, Orwell’s least good invective, I guess, would have been reserved for those who have not been slow to express their condescension for those who voted leave. I can see Orwell’s depiction now of that tribe of ‘progressives’ (opinions from Portland Place, cooking from Upper Street), making their dreary way, drawn to Brussels like bluebottles to a dead cat. One minute decrying the banks for bringing us to the cliff edge, the next minute shocked and afraid of the very same banks’ warnings about the dangers of a cliff edge that is not their cliff edge, we can be sure that as a conniosseur of the type, Orwell would have made note. He never liked the intellectual left’s severance from the common culture of the country, largely because he himself felt cut. But he would have enjoyed this admission from a fellow amputee:

‘…among my pretty extensive circle of friends and family not a single person that I could identify voted for Brexit. It was that bubble, that privileged ghetto – feeling completely disconnected from more than half the people – that made me feel very ashamed. My whole self-image was rather challenged by the realisation that the only people I mixed with were, broadly, sort of, metrosexual and liberal… I just thought, “Christ that’s terrible, terrible”.’

(Robert Peston, political editor at ITV News, in the Guardian, 27 November 2017)

So which Orwell?

We cannot be sure. Brexit is an unknown. Orwell was a contrarian. I suspect he would have regarded inequality as a more pressing issue. I’m sure he would have been especially attentive to the opinions of the European young and what they wanted. He had lived through the Norway and Dunkirk fiascos, and knew how cack-handed divided cabinets could be.

I honestly do not have a view on what he would have said about immigration. His implacable opposition to racism would have had to face off his intuitive belief in national self-determination. He might have been forced into difficult calculations about the propensity of Vote Leave to encourage the hard right, against the propensity of the EU to encourage Vote Leave – over uncontrolled immigration, for instance. And faced now with forms of news domination on the internet infinitely more complex and fragmented than anything to be found in his time in Berlin or Moscow (which he called ‘gramophones’), he might have saved his finest work for that. But from what we know now, and from what we know he knew then, it was the growing power of large and unaccountable states he feared most. Although Mrs Merkel’s EU is in some ways a great post-war German achievement, it bears the marks of a central European empire.

Robert Colls is a professor of cultural history at De Montfort University, and the author of George Orwell: English Rebel, published by Oxford University Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.