Long-read

America after the fall

The Royal Academy's new exhibition underplays the abstract side of 1930s American painting.

America between the wars (and specifically between the Crash of 1929 and the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack) was at a crossroads. The economic boom and expansion of American power following victory in the First World War had led to prosperity and optimism for many in the 1920s. The Crash of 1929 led to the Great Depression and – in a way – a Great Retreat. America First, isolationism and a backlash against globalism and Modernism caused Americans to view modern and foreign influences with mistrust. A new exhibition, America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, at the Royal Academy, explores American art at this crossroads.

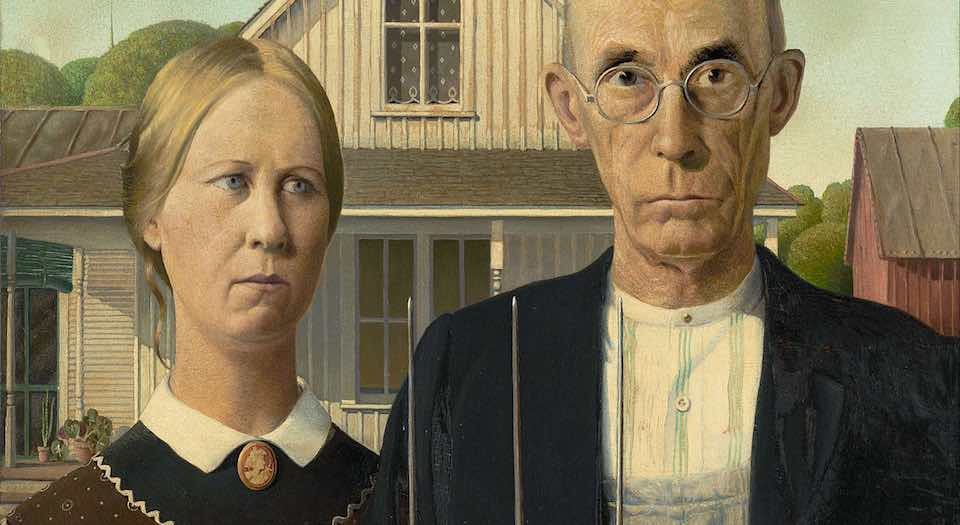

It includes pictures by some of the big names of American realist painting and includes an American icon: Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930). Although it is seen as typical of American homespun simplicity and Puritan honesty, the male figure is Wood’s dentist dressed as a farmer. The picture is subtle, well-painted and tinged by irony; it deserves its iconic status not only because of its popular appeal but also because of its artistry.

Wood was part of the Regionalist movement, a group of artists who sought to depict American life and landscapes in a realist manner, often with sentimental or nostalgic overtones. A fundamental debate at the time was whether American art could be both American and Modern. The association between Modernism and European ‘decadence’ was made by artistic and social conservatives, who advocated traditionalism applied to local American subjects, which came to be called Regionalism. Regionalists like Wood were stylistically conservative but had a variety of political views. They chronicled the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl (a result of disastrous agricultural policies and drought) and Klu Klux Klan lynchings. Regionalism was in large part focused on rural life, though the artists themselves did not all live in the countryside.

There is an overlap between the Regionalists and the social realists in their overt social agendas. Typical subjects for Social Realists were working conditions, urban life and industrial relations. Their satirical paintings often combine both criticism and celebration of America’s urban vulgarity. Though the peak of the black Harlem Renaissance was over by the 1930s, there are some paintings here of black life. Other paintings depict the infamous dance marathons, the cinema, home life and sailors on shore leave.

Edward Hopper’s painting of a rural gas station juxtaposes landscape and American automotive infrastructure with his usual melancholy restraint. Charles Sheeler’s Precisionist paintings of industrial scenes are one of the great milestones of American realism and are excellent records of America’s heavy industry. Sheeler was a painter who developed a technique that suited his temperament and his subject matter, which included industrial buildings, offices, railways and the clear edges and smooth surfaces of machinery.

A strong strand of social engagement is apparent in most of the art on show. When artists were not depicting social conditions they tackled outright political subjects (domestic and international). Of the popular artists, only Georgia O’Keeffe used abstract elements; reliance on local imagery made her art relatable and American. Other painters included in this exhibition are Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Stuart Davis, with the stand-out artists being Hopper, Wood and Sheeler.

Art historically speaking, there are some missteps.

Surrealism is over-represented here. While there is virtue in seeing new artists, these are rather mediocre ones; it is no surprise that the quasi-Surrealists on display, such as Helen Lundeberg and Federico Castellon, are unknowns.

Some significant artists are omitted. To have an exhibition of this character and exclude John Sloan and Milton Avery is disappointing. A landscape by Maxfield Parrish would have been welcome. Parrish is virtually unknown this side of the Atlantic and this would have been a good opportunity to introduce his work but there is nothing by him here.

Perhaps the focus on realism explains why curators and authors have underplayed the influence of the American government’s Works Progress Administration in the catalogue essays and work selection. The WPA commissioned paintings in order to alleviate poverty among artists and to bolster Roosevelt’s New Deal campaign to spend on public goods. The WPA proved a crucial patron for Modernist artists in a time when the economic market for difficult-to-sell Modernist art was almost non-existent. Due to the recent Abstract Expressionist exhibition at the Royal Academy, the works of all those artists (with the exception of a good early Jackson Pollock painting) have been excluded from this selection. While an understandable decision, the exclusion of the future Abstract Expressionists produces a strong bias in favour of realism and against abstraction. Despite the historical dominance of figurative art, abstraction is under-represented here.

Despite slips, America After the Fall has many good pictures by artists who are rarely seen in Britain and is worth a visit.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s is at the Royal Academy until 4 June 2017.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.