Two sides of our moral malaise

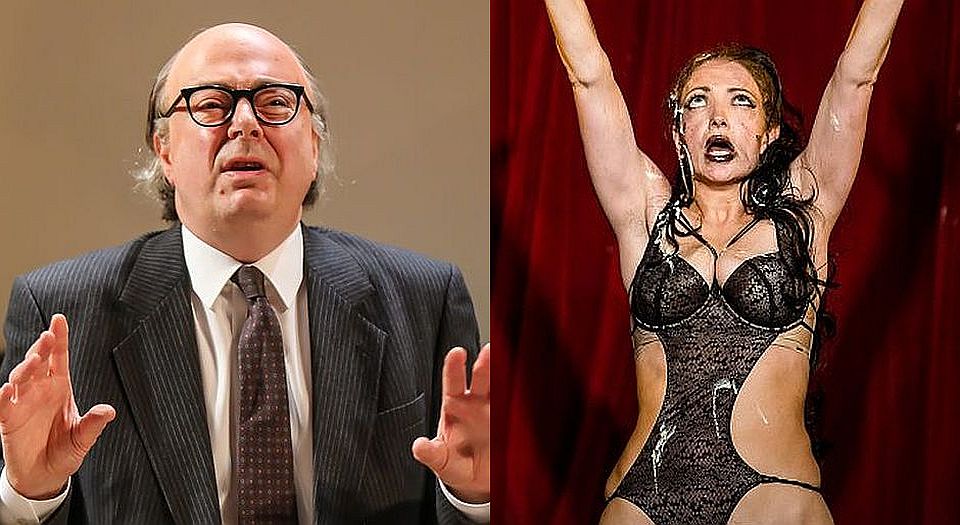

A charming play about the SDP and a vacuous cabaret show both speak to these confused times.

What a difference a postcode makes. In Convent Garden’s Donmar Warehouse theatre, designated as WC2H, you can see a sweet and even charming play about the origins of the short-lived Social Democratic Party (SDP), which was set up as an alternative to Britain’s dominant Labour and Tory parties in 1981. It was founded by the so-called Gang of Four: Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams. Meanwhile, at the Soho Theatre in neighbouring W1D, cabaret artist Lucy McCormick is staging an obscene re-enactment of the New Testament in which, as Jesus, she is vividly finger-fucked by the doubting disciple, Thomas.

It’s hard to imagine two more different shows, yet they both speak eloquently – if not always knowingly – to the social and political malaise of our times.

Steve Waters’s play Limehouse at the Donmar is set in David Owen’s docklands home at a time when that part of the East End was just beginning to be redeveloped by the emerging yuppie classes. Owen is found having a crisis of faith, forcefully expressed by the play’s opening line: ‘The Labour Party’s fucked!’ Teeing us off with an easy laugh, this is a passionately cosy piece of work which sees the Gang of Four converging on Owen’s house as they launch their short-lived attempt to seize what they perceive to be the empty centre ground of British politics.

Tom Goodman-Hill’s David Owen is incandescently moderate, and is persuaded by the formidable Nathalie Armin as his American publisher wife Debbie to convene the meeting and save the nation’s political life. First arrives Paul Chahidi’s good-natured Bill Rodgers who is presented as an old-school working-class Labour man from a long line of honourable Labour men. His crisis over betraying his party is translated into a case of acute sciatica after he opens a bottle of Chateau Lafite 1964. Then along comes omni-cheery Shirley Williams, powering good sense into the occasion, before the terrific Roger Allam finally pitches up as the frightfully posh but thoroughly clubbable European Commission president, Roy Jenkins.

The discussions that follow are meant to shadow our own times, with a Tory Party in the ascendancy, untroubled by a divided Labour Party nominally led by an inept and ineffectual old man (Michael Foot). Parallels with today need little exposition, but there are also amusing political insights. One such is how for the Tories the only crime is failure, whereas the Labour Party is closer to a religion, treating dissenters as heretics and apostates. Waters writes with warmth and intelligence about each of his characters, but the truth remains that those times don’t entirely map on to our own, not least because of the Heraclitian wisdom that you cannot step into the same river twice.

I was reminded of a line from a trashy thriller about American mercenaries I read a long time ago, in which the main man sneered ‘the only thing in the middle of the road is yellow lines and dead armadillos’. The trouble is that whatever else you can say about the political figure of speech known as ‘the centre ground’, it’s very hard to get passionate about it. But it’s even more of a problem for these four crusaders for the common good to get mobilised on it. They have neither finance, grassroots traditions nor followers to draw on. With only noumenal notions of reasonableness and instinctual good sense to offer would-be disciples, it was a miracle the SDP lasted seven years.

Today, in a nation of sectarian interest groups, regional tribes, transient populations, socio-economic divides and non-conversant cultures, how can you give meaning to such specious categories as ‘the centre ground’? The impossibility of doing so is what makes politicians invoke such flimsy articles of faith as the British sense of fair play. What we do have in common with 1981 is a vacuum at the centre of our political and cultural life. That is partly why it’s possible for exhibitionists like Lucy McCormick to succeed. I had hoped that her antics might somehow embody the confusion of our times. Instead her extreme but largely puerile performance has no more vision than did the SDP.

Her show at the Soho Theatre, Triple Threat, is what psychologists might call hysterical ‘acting-out’ – behaviour that is the consequence of some compulsion into which the actor has no insight. The evening starts with an immaculate conception brought about with a dildo. Flanked by two camp young men, she is like Madonna-gone-hardcore performing a raucous virgin birth. We are then hit with travestied Biblical outtakes, including Mary Magdalen licking Nutella off of Jesus’s face. Judas gets in on the act with more deep-throat snogging, and the eventual assent into heaven is achieved by crowdsurfing to the exit.

Either all this is a satirical affront to Christianity or it’s an assault on the vacuity of popular culture. If it’s an attack on Christianity, it has chosen a soft target which can’t, won’t and, in line with doctrine of turning the other cheek, shouldn’t fight back. Had McCormick chosen to give Islam the same treatment she would surely be dead by morning. If on the other hand her target is pop culture this show is too scattershot, and her singing of saccharine pop anthems is too glib. Maybe she isn’t trying to do either of these things; the audience are content merely to snigger and guffaw as the mood takes them. She even tells them off for being too easy. Cue more laughs.

I found the evening utterly depressing. The Soho Theatre has for the most part given itself over to the cult of identity politics, and cross-dressing transgenderism is its principal preoccupation. To her credit, McCormick doesn’t fit neatly into that box and her style is perhaps more attuned to that of the nearby Raymond Revuebar. What is particularly bleak, though, is how she shares the dead-end genital fixation of identity politics, which reduces human beings to transactable biology. In a time when anything goes, nothing is valued. If these two shows have any significance it is perhaps in bearing out WB Yeats’s gloomy line in his 1919 poem ‘The Second Coming’, where he says ‘the best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity’.

Patrick Marmion is a playwright, journalist and associate lecturer at the University of Kent. He is currently adapting Will Self’s Great Apes for the stage.

Limehouse is at the Donmar Warehouse until 15 April.

Triple Threat is at the Soho Theatre until 22 April.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.