Turkey needs some Brexit spirit to defeat Erdogan’s tyranny

From Brussels to Istanbul, elites are in revolt against democracy.

Around the world, democracy, the hard fought-for humanist ideal that ordinary people must have the right to steer their nation’s destiny, is under attack.

The attack takes different shapes in different places. In countries like France, Holland and Ireland, democracy was mortally wounded through simply being ignored: those nations’ mass, majoritarian cries of opposition to the EU Constitution were casually brushed aside. In Brexit Britain, democracy is chipped away at politely, by businesspeople, ex-PMs, legal minds, unelected lords and an angry chattering class keen to override the anti-EU stand taken by the apparently ‘low information’ majority. In Trump’s America, the anti-Trump establishment openly calls for more checks on popular opinion, to tame plebs’ ‘untrammelled emotions’. And in Turkey, as we saw yesterday, democracy is throttled through the firm, jealous consolidation of presidential power.

Some European observers, who, post-Brexit, view every referendum as a threat to stability, if not a Hitlerian device of mayhem, are talking about Erdogan’s referendum to give himself sweeping powers in the same breath as the Brexit referendum. Both the ‘Brexit and Erdogan referendums are illegitimate’, says philosopher turned anti-democrat AC Grayling. A Europe ‘traumatised by Brexit’ hasn’t a leg to stand on when it comes to challenging the authoritarian Erdogan, says a writer for the Guardian.

These attempts to link Brexit with Erdogan are beyond wrong. In truth, Erdogan’s campaign to weaken parliamentary democracy in order to sideline pesky oppositionists and to streamline political decision-making is far more in keeping with the Remainer / EU worldview than with Brexit. It’s another expression of the 21st-century elite turn against democratic ideals that the anti-Brexit sentiment, the establishment fury with the Trump throng, and Brussels’ power-grabbing constitutions – rejected by millions of Europeans – also express and embody.

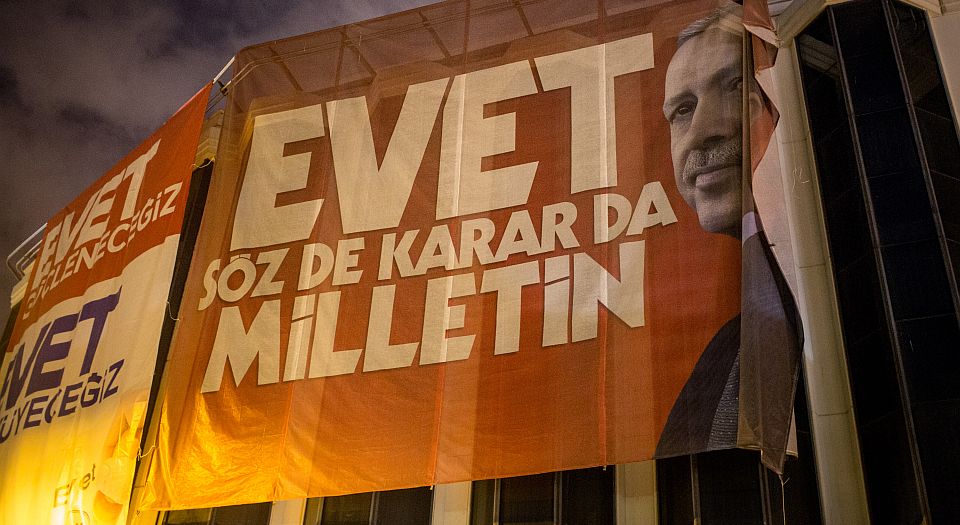

Erdogan won the referendum on expanding his powers by a slim majority: 51.3 per cent said Yes to his plans; 48.7 per cent said No. He won by 1.25million votes, in a referendum in which 47.5million people – 80 per cent of the electorate – voted. The results are being disputed, and with very good reason: over the past few months Turkey has witnessed the jailing of oppositionists, the purging of Erdogan’s critics from public life, and a war on media freedom, meaning this was far from a normal, open, free electoral campaign. Indeed, election results become close to meaningless when one side of the debate is silenced, battered or imprisoned.

Erdogan’s new powers should chill anyone who believes in democracy and liberty. He has shifted Turkey from its founding aspiration to be a secular parliamentary democracy towards being a pretty ruthless executive presidency. He will now be able to govern until 2029. The president – which will be him for the foreseeable future – will have the power to appoint ministers, choose the country’s top judges, and even force through some laws by decree. It’s a recipe for authoritarianism, a blow against parliamentary democracy and debate, and a cynical attempt to elevate the doing of politics above public discussion and accountability.

This isn’t Brexit; it’s the opposite of Brexit. Brexit was a vote against precisely the kind of separation of politics from testy parliamentary and public scrutiny that Erdogan is now pursuing. Brexit was a cry for greater parliamentary sovereignty, for people’s votes and voices truly to mean something, and for ‘the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK’, as the post-referendum Ashcroft Poll found – that is, that the British parliament, consented to and elected by us, should make the laws we live under, not the increasingly executive, distant and unaccountable machine of the European Commission.

In essence, Erdogan has done within his own nation what the EU apparatus, and most importantly the EC, does on a continent-wide scale. Just as the EC insists that its powerful members, these unknown, unreachable commissioners who draft laws for 500million people, must be ‘neutral from other influences’, including the influence of their home nations and domestic parliaments, so Erdogan aspires to make law and policy ‘neutrally’ from Turkey’s parliament. Just as Brussels justifies its post-debate, expert-led technocratic policymaking as a necessity in this globalised era of climate change, terror and migrant crises, so Erdogan made his stab for greater power through raising the spectres of terrorism and extremism and arguing that the political solutions to such problems must be made swiftly and firmly. Indeed, in using fear to drum up support for his powers, Erdogan echoed the Project Fear of elite Remainers far more than the risk-taking of Brexit voters. His consolidation of power is the latest, and one of the clearest, examples of the turn against democracy that can now be glimpsed everywhere from Brussels to Twitter to the Guardian to the coffee shops of a Silicon Valley horrified by the Trumpite mass.

But there are reasons for us democrats to be optimistic even in the face of Erdogan’s alleged victory. That he won by such a slim majority is extraordinary given the terrifying, authoritarian efforts he put into shutting up or shutting down his opponents and critics. Following the failed coup against him last July, around 150 journalists have been jailed and 170 media outlets have been shut down. More than 2,500 journalists have lost their jobs, and some have lost their press cards and even their passports, all of which has shrunken the public space for Erdogan-critical commentary. MPs have been arrested, including leaders of the Kurdish People’s Democratic Party. Critics of Erdogan have been purged from the judiciary and other areas of public life. Yet despite all this tyrannising, Erdogan spectacularly failed to win the 60 per cent support he was hoping for. Millions of Turks braved the illiberal hysteria he whipped up and said ‘No’ to him. As a writer for the Wall Street Journal says, that Erdogan won by ‘such a thin, and contested, majority may threaten his ability to govern unchallenged’.

Let’s hope it does. And Westerners who care for democracy and liberty can help to ensure it does by offering our solidarity to Turks who want more openness, more freedom, more debate, and more say. At the front of this solidarity should be Brexiteers, because we share an enemy with democratic Turks: the relentless, top-down ‘streamlining’ of politics at the expense of parliamentary debate, open contestation, and the idea that the people – even allegedly ‘low information’ people – should get to shape public and political life.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.