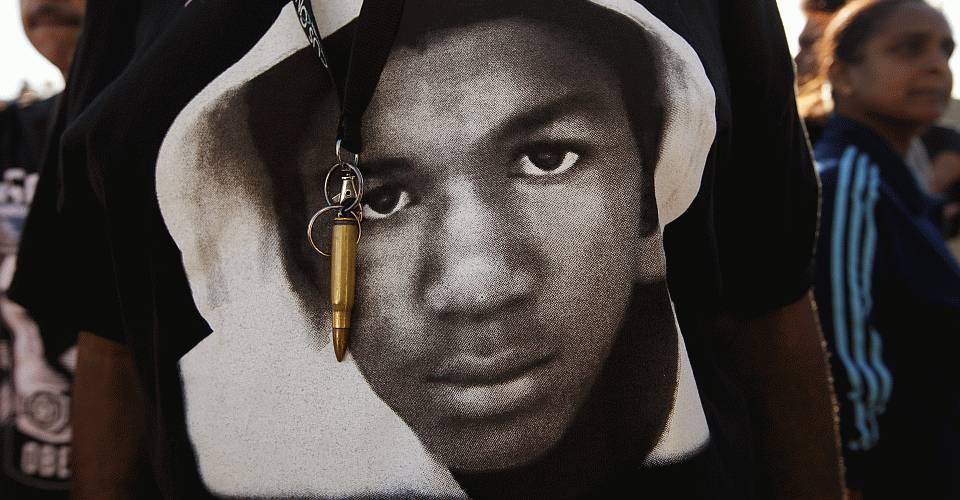

Trayvon Martin case: who’s really promoting prejudice?

The pro-Trayvon campaign shows how illiberal ‘anti-racism’ has become.

Whatever one’s opinion of the verdict acquitting George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, it doesn’t change the sad reality that a 17-year-old died well before his time. Who could not be moved by the sight of Martin’s grieving parents? They sat in the courtroom knowing no matter what the verdict, it wasn’t going to bring their child back. That’s the image that haunts us.

Hearing about the case, there is a natural tendency to want to try to figure out how and why Martin was killed, and to make some sense of it. The events were disturbing, to say the least: an adult follows an African-American teenager who he believes is acting suspiciously, and ultimately shoots him dead.

But shortly after that tragic encounter between Zimmerman and Martin on a February night last year in Florida, and before many facts of the case were known, campaigners from across America jumped to the conclusion that the case was a clear and prime example of everything that’s wrong with the US, especially regarding race relations. Zimmerman, in their eyes, was a racist and a murderer.

Campaigners’ far-reaching claims were an attempt to score political propaganda points rather than to get to the truth about what actually happened that evening. And they placed a tremendous amount of weight on a case involving two people in a small Florida town. You can’t really draw sweeping conclusions about society from a single, complicated case like this one. Whatever verdict was reached by the jury, it wasn’t going to prove the extent or intensity of racial discrimination in America today one way or another.

As anyone who followed the trial will have noticed, there was a sharp contrast between the often mundane details of the case itself and the hyped-up political circus around it. A local dispute became nationalised, with even President Obama weighing in to say: ‘If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon.’

National campaigners pushed the line that Martin’s killing showed that old-style American racism is alive and as bad as ever. Evoking a 1955 case that inspired the civil-rights struggle, black commentator Touré said after the verdict: ‘We still live in the same America that Emmett Till lived in, an America where blacks are often judged to be a threat to order and citizens are able to destroy their bodies.’

In making this argument, however, liberal campaigners had to twist the facts to fit their simplistic storyline. Zimmerman was initially described as ‘white’, but after it became known that he was of Hispanic background, they invented a new term, ‘white Hispanic’, so as to continue the white vs black narrative. NBC edited a recording to make him sound like he had made a racist comment about blacks, which they later had to admit was doctored. Zimmerman was portrayed as a racist monster, yet it was revealed that he had many black friends, including a black girlfriend in high school. He reportedly voted for Obama. All in all, he didn’t fit the campaigners’ image of him as a KKK member.

With the eyes of the nation on the trial of Zimmerman, and with pressure from the president, the easy thing for the jury to do would have been to find him guilty. In that sense, the jury’s independence was admirable. But many pro-Martin liberals had from the beginning already convicted Zimmerman in their own minds, and were shocked when the jury did not confirm their presumption of guilt. So what do they do? Blame the jury (and by implication, trial by jury) for perpetuating injustice against blacks. Aura Bogado, writing in The Nation, said the six-woman jury must have followed the ‘logic of white supremacy’ – in other words, they were racist. She also faults the defence for citing the ‘slave-owning rapist Thomas Jefferson’. Others blamed a ‘Zimmerman mindset’ among whites, which has apparently ‘infected the criminal-justice system’.

These accusations of racism might sound radical, but they aren’t. Today, we’re told, the roots of racial conflict are not found in government policy (Obama and others are seen as anti-racist), nor among the elites generally (it is gauche to espouse such views in polite circles), nor even so much among the police. Instead, the blame for racism is put squarely on the shoulders of working-class types like Zimmerman.

There is a terrible irony to the response to the Zimmerman verdict: it is those who profess to be on the side of Martin and justice, who claim to be anti-racist, who are really promoting prejudice and illiberal solutions. The pro-Trayvon lobby promotes explicit prejudice against ignorant jurors, against crazed men carrying guns, against ‘white Hispanics’ and others who fail to appreciate all races. It is also the loudest critic of basic legal principles, such as innocence until proven guilty and reasonable doubt. The whole thing reveals how what now passes for ‘anti-racism’ has become a divisive outlook with authoritarian overtones.

Campaigners chose to make Trayvon Martin the focus for a national discussion of race in America. But it was never going to lead to an enlightened and rational debate. In seeking to personalise the issue and create an emotional tie through Martin’s case, campaigners dodged the significant structural and institutional barriers that give rise to racial inequality. And by portraying racism as something that comes from deep within the hearts of white people (so deep that whites often don’t even realise they’re racist), today’s elitist ‘anti-racist’ outlook makes racial divisions appear hopelessly insurmountable.

Clearly, there are significant social divisions among people living in the town of Sanford, Florida. Zimmerman lived in a ‘gated community’ – a concept that used to denote a rich, exclusive enclave, but has now been extended to even poor patches like Zimmerman’s. The dispute between Zimmerman and Martin, which could not be resolved peacefully, makes it seem like they came from totally different worlds. But for all those very real divisions, Zimmerman and Martin actually had more in common with one another, sharing the same town, than they did with the establishment politicos and media who parachuted in from Washington and New York after Martin’s death. Divisions in areas like Sanford are a real problem, but, sadly, ‘anti-racist’ campaigners and politicians have just made matters worse.

Sean Collins is a writer based in New York. Visit his blog, The American Situation.

Picture by: Jae C. Hong/AP/Press Association Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.