The end of the political party

Plans to rebrand the Conservatives reveal the shallowness of party politics.

And so the Conservative Party’s efforts not to be the Conservative Party anymore continue. Following in the footsteps of Tory MSP Murdo Fraser, who suggested quasi-independence and a new name for the voter-repellent Scottish Conservative Party in 2011, Conservative local government and planning minister Nick Boles has suggested an equally cunning plan to attract those people to the Conservative Party who don’t like anything about the Conservative Party: set up a new party.

It’s not a completely new party. In fact, Boles’ suggestion, the National Liberal Party (which existed between 1931 and 1968), is an old adjunct of the Tories proper. Still, its function would be very much of this era: to ‘detoxify the Tory brand’.

Speaking to Westminster Tory discussion group, Bright Blue, this is how Boles justified reviving the NLP: ‘The Conservative Party will only rebuild itself as a national party which can win majorities on its own if it understands that it cannot do so by making a single undifferentiated pitch to every age group and in every part of the country… We could use [the NLP] to recruit new supporters who might initially balk at the idea of calling themselves Conservative.’

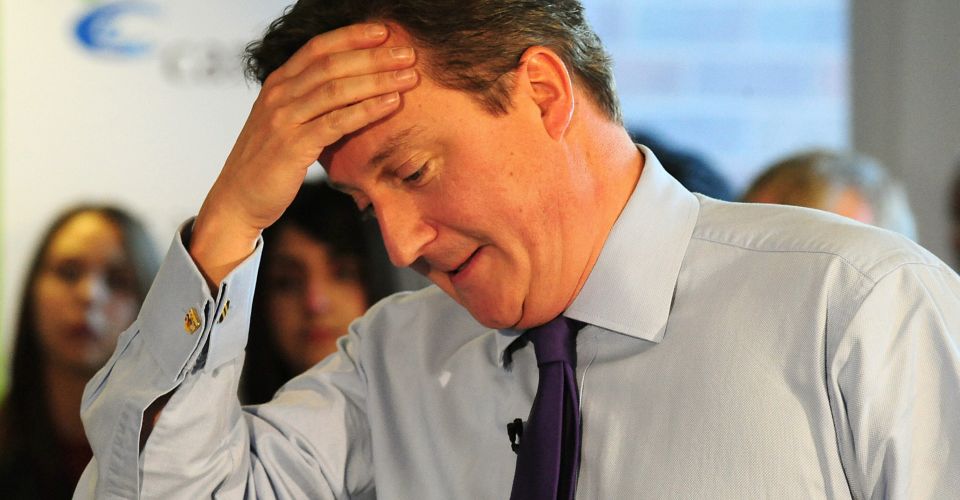

It’s an absurd, slightly disconcerting ploy, but the very fact that a Tory minister offered it up as a viable plan reveals much about the husk-like condition of Britain’s main parties – despite Tory leader and prime minister David Cameron dismissing the idea. Because what Boles highlights is how the political party, an institution, in the Tories’ case, built on hundreds of years of tradition and political struggle, is ceasing to be a political party at all. That is, even for the politicians themselves, the political party is no longer an embodiment of a set of ideas, a vision of how things ought to be given organisational form. In fact, the party in Boles’ telling doesn’t seem to be much at all. Rather, it is at most an electoral brand to be stamped on to a section of the political class, much as commercial logos are stamped on to bags of dried pasta.

The electorate, likewise, is reconceived as a market of consumers. We are not being asked to follow and support a particular vision of society bodied forth in a particular party. That relationship has been reversed: the party is now to follow the whims and prejudices of the people. As Boles defensively puts it: ‘[W]e have no hope of securing [young liberals’] support if we approach them with the same proposition that we use to woo our stalwart supporters.’ Can’t change people’s minds, then change the pitch, or better still, change the brand. The party exists here as a mirror of a voter’s wants, rendering its substance as will-o-the-wisp and protean as voters’ views are various, such is the logic of trying to be all things to all voters. Little wonder Boles feels comfortable blithely suggesting a flashy new party, albeit with an old name, as the solution to the Tory Party’s failure thus far to convince the majority of the electorate to actually vote for it. ‘We could use [the NLP] to recruit new supporters who might initially balk at the idea of calling themselves Conservative.’

If the sight of a political party disavowing its own residual identity is dispiriting, the spectacle of political commentators cheering Boles on has been just as bad. This, as far as they’re concerned, is the only way a political party can be today: up-to-date, and down wiv da kidz. ‘This isn’t a question of burying traditionalists’, writes Alex Massie in the Spectator, ‘rather of making a case for a Conservatism that seems in touch with the modern world and actually likes the United Kingdom as it is, not as it once was.’ Others echoed this sentiment with a variety of insightless platitudes about keeping up with the times. The party’s failure to do so, remarked one columnist, ‘is depressing for members who want their party to inhabit the messy, fast-evolving modern world’. No wonder the Tories are faring so badly, explains another: ‘The Tory brand remains toxic.’

It’s this idea of the Tories’ toxic brand that Boles himself is playing on when talking of starting a new party to appeal to people who just can’t bring themselves to vote Conservative. In 2002, the then Tory chairman, Theresa May, gave the problem its most memorable formulation when she said: ‘You know what some people call us: the nasty party’ – an oblique reference to liberal perceptions of the Tories as an intolerant party of the socially conservative. Indeed, ridding the party of its ‘nasty’ image, cleansing it of ideological toxins, seems to be the closest thing the party’s leader, Cameron, and his various allies including Boles, have ever had to a mission.

This is why press reports dating from Cameron’s election as leader in 2005 have almost always understood policy proposals in terms not of a political project but of this ‘detoxification’ struggle. A BBC news report in 2006 runs as follows: ‘Mr Cameron is attempting to rid the Conservative Party of its “nasty party” image by adopting a more conciliatory tone on social issues.’ Cameron himself put it thus in 2009: ‘If we do win the next election, instead of being a white, middle-class, middle-aged party, we will be far more diverse.’ This is what its leaders, and its liberal baiters/commentators, think the Tory Party should be today: not a vision of Britain drawn from the past, but a reflection of Britain as it is. The political party is no longer meant to change society; it is meant to keep up with social changes. No wonder ex-Tory prime minister John Major talked recently of Conservatives like himself feeling ‘bewildered’ and ‘unsettled’ by contemporary Conservative policies, especially the party’s stance on gay marriage.

Here we approach the meaning of this obsession with ‘detoxifying’ the Tory brand. It amounts to nothing less than an attempt to free the party of its tradition, of the values and beliefs that so many of its dwindling, ageing band of supporters still hold. Cameron, Boles and the vast majority of political commentators may present detoxification as a positive process. Indeed, at points, Cameron almost presents it as the means by which the Conservative Party can become something new: a diverse, hip party of the present. And, in a sense, ‘detoxification’ really is the modern Tory party becoming something different. But it’s doing this not through positing something new, but by negating something old. That is, detoxification is the art of becoming something through self-negation – the negation of the past, of everything that the party once stood for, and for many of those who still support it, still stands for. It is the equivalent of New Labour’s obsession with ‘modernisation’ over a decade ago, when it seemed to be constantly in the throes of emancipating itself from its own ‘let’s nationalise it’ past and traditions. In both cases, the process is presented as progressive; in reality it represents the hollowing out of the party, a severance of the organisation from its past, its roots, and in many cases, its actual supporters.

Not that Boles’ conception of the modern political party is entirely empty. Because just as old Tories are ridiculed, just as the past is denigrated, just as tradition is repackaged as toxicity, so youth, newness, the modern are made virtuous. This is why, as one report describes Boles’ speech, he is so keen to woo young voters. It’s as if the views of young people are automatically deemed the correct views; it’s as if every banality that falls from the mouths of babes is inherently progressive. Bereft of any intrinsic vitality or vigour, the modern political party reaches out to the idea of youth to fill the breach. Nor are the Tories the only ones to have set about abandoning their past in favour of fetishised youth; Labour is similarly besotted. ‘To change our politics’, said Labour leader Ed Miliband at this year’s party conference, ‘we’ve got to hear the voices of people whose voices haven’t been heard for a long time. The voices of young people… the voices of gay and lesbian young people, who won the fight and led the battle for equal marriage in Britain.’ Here, ‘young people’ are granted the history-making role the political party might have once arrogated to itself. Boles, too, is quick to join Miliband and his rainbow youth at the gay marriage barricades, arguing that the Tories should show off their role in institutionalising gay marriage: ‘We should not shy away from those achievements but shout them from the rooftops. They should make us proud.’

Sadly, like a fortysomething uncle in skinny jeans, political parties’ determination to hang out with the kids does not make them vital, purposeful bodies; it just illustrates their state of decomposition. They are not really political parties anymore; they are empty brands in search of the most electorally lucrative market.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture: PA/Press Association Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.