The SNP’s attack on democracy

The Scottish are part of the British demos, and should respect its decisions.

Ever since Scotland rejected independence from the UK in the 2014 referendum, the SNP leadership has been tirelessly looking for ways to trigger a second referendum. And in the UK’s EU referendum result, in which 53 per cent of the English electorate voted to leave and 62 per cent of the Scottish electorate voted to remain, the SNP thinks it has found one.

The SNP’s threats of a second referendum on Scottish independence have often seemed empty. Though many grassroots independence enthusiasts openly supported – even campaigned for – Brexit on the basis that it might lead to another shot at independence, the outlook of the SNP leadership has been more cautious. To lose a second referendum on independence would bury the cause for a generation. And the conditions are unfavourable, with the price of oil much lower than in 2014 and many of the key questions that hung over the SNP’s 2014 campaign – currency, membership of the EU – still unanswered, and perhaps even more complicated than before. True, many Scots who voted No to Scottish independence resent being taken out of the EU. But with one post-EU-referendum poll putting support for independence from the UK at 52 per cent, it is at best unclear whether this resentment will be enough for the SNP to win a second referendum, especially when passions on both sides subside.

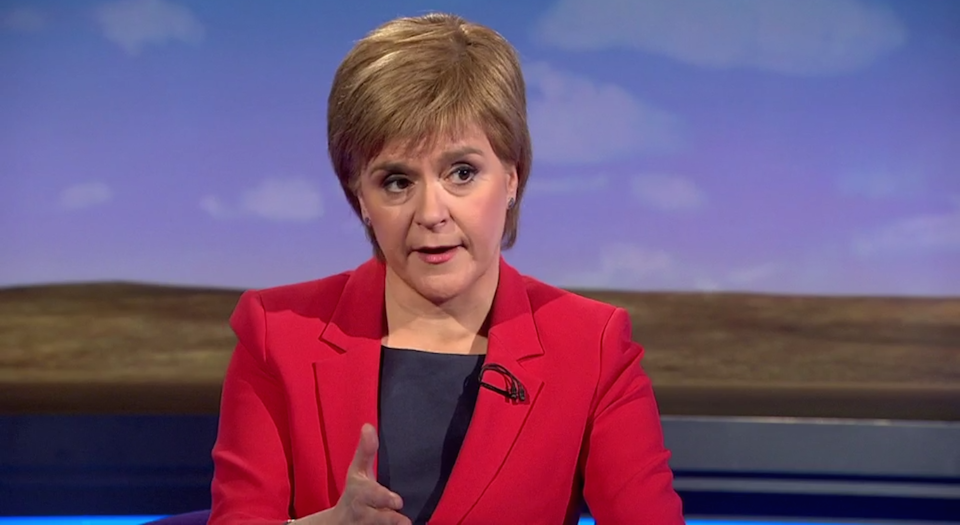

So why, then, did SNP bigwig Alex Salmond immediately call for SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon to implement her recent (and intentionally vague) manifesto commitment to hold another independence referendum in the event of a ‘material change of circumstances’? Why was Sturgeon so quick to announce from the steps of Bute House in Edinburgh that, in light of Brexit, a second referendum is ‘highly likely’?

Partly it is because the SNP’s hand has been forced. It really did support the UK’s membership of the EU, and its threat of a second referendum in the event of Brexit was intended to make that outcome more attractive. If it backtracks now, that threat forever loses credibility. But there’s more to it than this. After the SNP’s victory in the Scottish elections in May, and the significant margin of victory for Remain in Scotland, there’s a sense within the SNP’s ranks that a grave injustice has been committed – that there exists a new democratic deficit so great that the SNP has no choice but to offer independence immediately. As Humza Yousaf, one of the more cautious SNP ministers, tweeted shortly after the result: ‘We have united to say our place is in the EU. To be dragged out would be indefensible.’

Well, here’s a defence. First, it’s worth noting that about as many voters in Scotland voted to leave the EU as voted for Sturgeon’s manifesto in the recent Holyrood elections. Last month, 25.8 per cent of the electorate backed the SNP on the constitutional vote; in the EU referendum, 25.5 per cent backed Leave. Of course, more backed Remain, but Remain was not a vote for a second independence referendum, and if an overall UK leave vote is supposed to be the ‘material change in circumstances’ required for a second referendum, then we should expect the electorate’s backing for that to be significantly higher than the backing for Leave. But the support is effectively the same. This calls into question the strength of the mandate for a second referendum.

But even if that support had been significantly higher, there’s a more fundamental point to make here. On Monday, Sturgeon told BBC News that she might consider using a veto to stop Britain leaving the EU. When she was asked about the fury this would unleash in the rest of Britain (and, indeed, in Scotland), she responded by saying that ‘it’s perhaps similar to the fury of many of people in Scotland right now’ with respect to the EU result. The fury felt may well be the same – but the political circumstances are not.

In 2014, we voted, as a nation, to be bound by decisions made at the UK level. A majority of Scots said, ‘We are part of the British collective. Its decisions are ours.’ Why would that include elections and other political decisions, but not constitutional decisions about the EU? The standard SNP response here is to say that we voted for a UK inside the EU, not outside, and so the 2014 result is void. But think about what this would mean, taken to its logical conclusion. It would mean that any deep, significant decision taken by the British demos would nullify the outcome of the independence referendum. The lasting validity of ‘No’ to Scottish independence would effectively require British political stasis. Was that on the ballot paper in 2014? Or did ‘No’ to independence mean ‘Yes’ to the British people’s decisions, no matter how game-changing?

Blair Spowart is a writer and a student at the University of Edinburgh. Follow him on Twitter: @blairspowart

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.