Standing up to the white-coated gods of fortune

Science has replaced Fortuna in fancying itself as the revealer of men's fates.

Fate is making a comeback. The idea that a human being’s fortunes are shaped by forces beyond his control is returning, zombie-like, from the graveyard of bad historical ideas. The notion that a man’s character and destiny are determined for him rather than by him is back in fashion, after 500-odd years of having been criticised and ridiculed by humanist thinkers.

Of course, we’re far too sophisticated these days actually to use the f-word, fate. We don’t talk about a god called Fortuna, as the Romans did, believing that this blind, mysterious creature decided people’s fates with the spin of a wheel. Unlike long-gone Norse communities we don’t believe in goddesses called Norns, who would attend the birth of every child to determine his or her future. No, today we use scientific terms to argue that people’s fortunes are determined by higher powers than their little, insignificant selves.

We use and abuse neuroscience to claim certain people are ‘born this way’. We claim evolutionary psychology explains why people behave and think the way they do. We use phrases like ‘weather of mass destruction’, in place of ‘gods’, to push the idea that mankind is a little thing battered by awesome, destiny-determining forces. Fate has been brought back from the dead and she’s been dolled up in pseudoscientific rags.

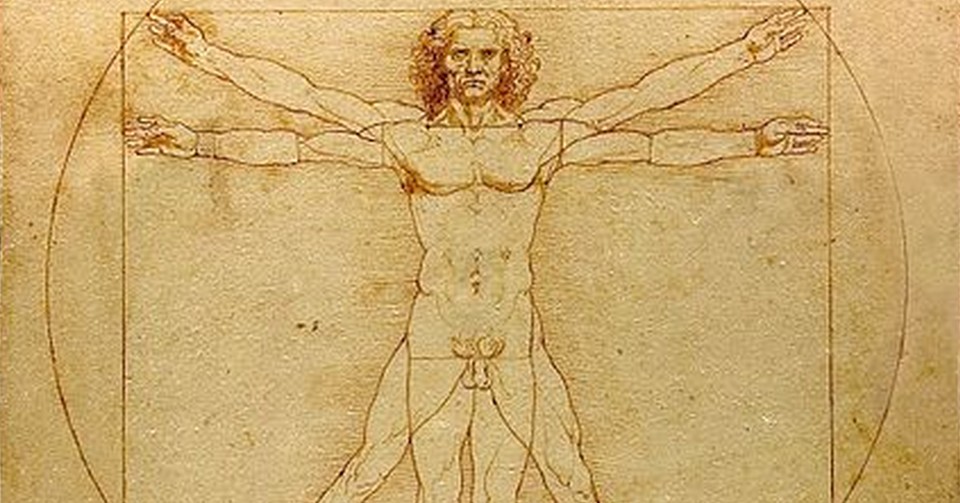

The intellectual challenge to the idea of fate was one of the most significant things about the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. There had always been an inkling of a belief within mankind that it was possible for individuals to at least influence their destiny, if not actually shape it. The Romans, for example, believed Fortuna would be kinder to brave, virtuous men. If you did good and took risks you had a better chance of being smiled upon by Fortuna. ‘Fortune favours the brave.’ But it wasn’t until the Renaissance that the idea that men could make their own fortunes really took hold. It’s then we see the emergence of the belief that by exercising his free will, a man can become master of his fate.

The earliest texts in Renaissance Italy devoted themselves to questioning the idea that man is the prisoner of a preordained destiny. Francesco Petrarch was one of the first humanists. His 1366 book Remedies For Fortune Fair and Foul argued that, alone among God’s creatures, mankind has the ability to control his destiny. Giannozzo Manetti, in his 1452 book On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, said men could shape their own fates by ‘the many operations of intelligence and will’. Also in the 1400s, the Italian scholar Leon Alberti said it was possible for individuals to reach ‘the highest pinnacle of glory’, even though, as he put it, ‘invidious Fortune opposes us’.

In short, mankind is a self-willed, autonomous creature. He’s a potentially more powerful force than Fortuna. In the words of the twentieth-century philosopher Eugenio Garin, the motif of the Renaissance was this: ‘It is always open to men to exercise their virtue in such a way as to overcome the power of Fortuna.’ (1)

It’s hard to overstate what a radical idea this was at the tailend of the Dark Ages. It’s this idea that gives rise to the concept of free will, to the concept of personality even. And it was an idea carried through to the Enlightenment and on to the humanist liberalism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the words of the greatest liberal, John Stuart Mill, it is incumbent upon the individual to never ‘let the world, or his portion of it, choose his plan of life for him’.

But today, in our downbeat era that bears a bit of a passing resemblance to the Dark Ages, we’re turning the clock back on this idea. We’re rewinding the historic breakthroughs of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, and we’re breathing life back into the fantasy of fate. Ours is an era jampacked with deterministic theories, claims that human beings are like amoeba in a Petri dish being prodded and shaped by various forces. But the new determinism isn’t religious or supernatural, as it was in the pre-Enlightened era – it’s scientific determinism, or rather pseudo-scientific determinism.

There’s neuro-determinism, the idea that we’re fundamentally products of the accidental shape or chemical liveliness of our brains. Everything from our criminal instincts to our musical giftedness to our political orientation is now said to have been bestowed on us by the grey matter in our heads. A recent study on the ‘neurobiology of politics’ claimed that whether a person becomes a liberal or a conservative depends on his ‘brain circuits’, particularly the circuits that deal with conflict. So now, we can’t even choose our political outlook, apparently; we’re not even in control of our voting destinies.

Then there’s evolutionary determinism – the idea that we’re compelled by what one author calls our ‘evolutionary wiring’. We’re told that our passion for consumerism is an evolutionary trait, a product of our ‘primitive, instinctive brains’, in the words of green writer John Naish, which drive us to ‘get more of everything, whenever possible’. Some experts even claim there’s a ‘rapist gene’, another byproduct of natural evolution and the instinctive urge of men to procreate. Once again, the ability of mankind to make moral judgements about his behaviour, to be the author of his life, is undermined by the idea that we’re hardwired to behave a particular way.

There’s also the rising trend of infant determinism. So-called ‘early years’ theory claims that a person’s life fortunes are determined by whether his mother breastfeeds him, his father reads to him, how much he’s cuddled, and so on. Books with titles like Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain claim that bad parenting can inflict ‘lifelong handicaps’ on children. In short, every mum and dad is a mini-Fortuna, and all of us are apparently just the damaged end products of what our parents said and did to us. We’re not the shapers of our own characters but rather are creatures whose fates were sealed by others before we hit the age of five.

And of course there’s environmental determinism, the trend for personifying the weather and the sea and the air, depicting them as god-like thwarters of human fortunes. Environmentalist determinism most closely resembles the old, pre-modern belief in gods of fortune. So in response to floods and other strange weather events, a respected British environmentalist has written: ‘From the storm clouds, the hand of God reaches down, clutching a large piece of paper labelled “the bill’.’ In other words, Nature, godlike and furious, is exacting her revenge on rampaging mankind.

These modern determinisms are far worse than the old pre-modern belief in fate. At least ancient communities, like the Romans, believed that by being brave and virtuous an individual could offset the harshest judgements of the gods of fortune. The new determinism offers no such scope for the exercise of bravery or autonomy. Instead it demands that we be meek and apologetic in the face of awesome powers like angry nature. It demands that we accept that tiny cliques of experts – whether brain-scanners, parenting gurus or climatologists – are the only ones who can reveal to us our fate and advise us on how to prepare for its inevitable playing out. It tells us we’re not really the subjects of history, but the objects of history, tossed about by this and that powerful force.

In such a stifling climate, we could do with a new Renaissance. We could do with declaring a war of words on today’s fatalistic experts just as surely as the scholars of the Renaissance stood up to invidious Fortuna. We could do with asserting the ability of human beings, through the exercise of their free will and the deployment of their moral autonomy, to shape their futures. To that end, in the coming months spiked will be publishing a series of essay designed to demolish modern-day determinism, and big up the dignity and excellence of man.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.