spiked’s heroes of the year

Our favourite people who defied the odds in 2016.

As 2016 draws to a close, we pay tribute to those individuals who stoked spiked’s fires — the independent-minded, the courageous and those who simply showed some cojones. Here are our heroes of the year.

Cincinnati Zoo

When a little boy fell into the gorilla enclosure at Cincinnati Zoo, Thane Maynard, the zoo director, made a swift, life-saving decision. He ordered security to shoot dead Harambe, the 400-pound silverback, who, having spotted the boy, had started to drag him into the enclosure’s moat. But such is the depth of animal-rights campaigners’ misanthropy that no sooner had Cincinnati Zoo saved the boy’s life, at the cost of one of their most important and valuable attractions, than a petition entitled ‘Justice for Harambe’ was launched, accusing the boy’s parents of negligence, and demanding an investigation of their home life. As far as the Justice for Harambe crew was concerned, what mattered was not that a young human’s life had been saved, but that an old ape’s life had been snuffed out – what mattered was animals, not humans. And yet despite the weight of social-media-stoked, memefied criticism coming the zoo’s way, Maynard stood firm: I would make the same decision again, he said. Against the misanthropists, Cincinnati Zoo affirmed the value of humans.

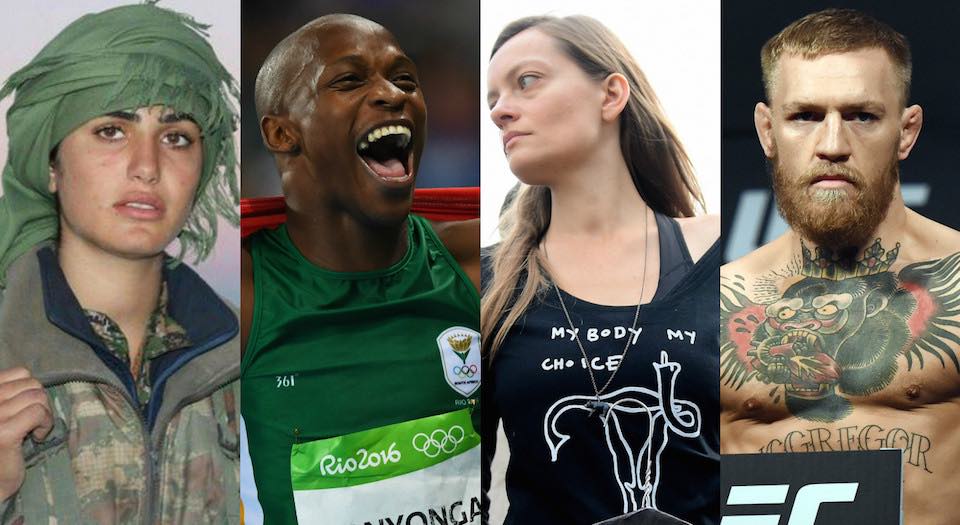

Luvo Manyonga

When South Africa’s 25-year-old Luvo Manyonga jumped 8.37 metres in the Rio Olympics long-jump final — a jump that was eventually to land him a silver medal — it was more than a significant sporting achievement. It was also an immense personal achievement. This was a man who had spent the majority of the past four years on the performance-detracting drug, crystal meth; a man who had been banned for 18 months in 2012 for his meth use; a man who had sunk into deeper, darker, drug-addled waters when his trainer and mentor, Mario Smith, died in a car crash in 2014. But there he was, in 2016, competing well beyond expectations, and only beaten into second place by a single centimetre. In this, he showed himself to be someone who refused to let his past determine his future. ‘I can be the best jumper in the world right now’, he said recently. ‘It won’t take me long. By next year you will see flames.’

Asia Ramazan Antar

Nineteen-year-old Kurdish soldier Asia Ramazan Antar, from the Syrian Kurdish city of Qamishli, was killed by ISIS fighters in northern Syria in August. In a sense, there was nothing remarkable about her. As a five-battle hardened team leader and a machine gunner in the YPG, she was simply one of hundreds of other Kurdish fighters who have died trying to do what the UK and its allies have merely waxed bombastic about – defeat ISIS. But, singled out by Western media because of her gender, and her good looks, she was transformed into the poster girl for the Kurdish struggle against ISIS. This was a bad move. Not because her story wasn’t heroic. It was, but it wasn’t uniquely so, and it certainly had nothing to do with her gender. Rather, her heroism is representative – representative of all those, including six of her own cousins and uncles, who have been willing to die for something worth fighting for: Kurdish self-determination and the destruction of the Islamic State.

Poland’s pro-choice protesters

In October, Poland’s government attempted to roll back the already limited reproductive rights of Polish women. As it stood, women were only allowed to seek an abortion in cases of rape, incest, threats to the mother’s health, and fetal damage. But under the new proposals, even a miscarriage would be grounds for a criminal investigation. Polish women fought back. They hatched campaigns, launched petitions, and on the day of the parliamentary vote, they staged strikes, demonstrations and class walkouts. Over 30,000 people then amassed in Warsaw’s central square, chanting ‘We want doctors, not missionaries!’ and carrying placards bearing messages such as ‘women just want to have FUN-damental rights’. It worked. Parliament voted against the proposals, and Poland’s science minister declared that MPs had been taught humility by the protesters. The fight’s far from over, but it was an impressive start.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone

With political commentators, too often marooned on islands of right-thinking likemindedness, comprehensively failing to get a handle on the US elections, it was left to a cartoon series that looks like it was drawn by a six-year-old to provide the insight. And boy did South Park deliver. The satire was as gloriously, deviously unsubtle as ever, with a Trump-a-like presidential candidate, referred to as the Giant Douche, desperate not to win because he doesn’t have a clue what he’d do, up against a version of Hillary, known as Turd Sandwich, who is so robotic in her denunciations of the Giant Douche that she paves the way for his victory. In a desert of conformism, South Park remains an oasis of infantile, scatological brilliance.

Alex Zanardi

For an example of grit, a determination to overcome adversity, look no further than than 49-year-old Alex Zanardi. In 2001, Zanardi, then an ex-F1 driver competing in a Championship Auto Racing Teams race in Germany, emerged from the pits with just 12 laps to go. He lost control of the car, which span sideways on to the race track, and into the oncoming race cars. One, slicing Zanardi’s car in two, ripped his legs off, one above and one below the knee. Zanardi was done as a sportsman. Or so you’d think. But, following an attempt to begin racing cars again using prosthetic limbs, Zanardi discovered hand-cycling, finishing fourth in the 2007 New York Marathon. That was it. Another sport, another objective – and one he duly realised at the London 2012 Paralympics, where he picked up two golds and a silver in hand-cycling events. This year at the Rio Paralympics, 15 years after losing his legs and nearly his life, Zanardi was once again on the podium, picking up another gold in the hand-cycling road time trial. This is a man who never knew when he was beaten, who never accepted what appeared to be his limits – and promptly surpassed them as a result. Little surprise then that Zanardi is now planning a return to motorsport.

Bangladeshi atheists

Earlier this year, Nazimuddin Samad, a 28-year-old law student at Jagannath University, was shot and hacked to death while out walking in the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka. The reason? He was an advocate of secularism, an atheist who wasn’t afraid to express his views on social media. Which, given what has happened since 2013, and the emergence of a new secular movement in Bangladesh, perhaps he should have been. Because over the past three years, a total of 48 people, 20 of whom were foreign nationals, have been killed in Bangladesh by militant Islamists. Atheist bloggers, secularist lecturers… they’re all deemed fair game for the self-styled protectors of Islam. The Bangladeshi state has responded, not by arresting the murderers, but by rounding up atheist bloggers. And yet despite this dual threat from state and Islamist alike, atheists like Samad are still prepared to stand up for what they believe in (or don’t believe in, in this case). Their bravery in the face of intolerance ought to be an inspiration to us all.

The 17.4million

Before the referendum, they were told they risked the economic meltdown of the UK; they were told a Third World War could be on its way; they were told they didn’t know what they were doing. After the referendum, they were told they were racist; they were told they were duped; and they were told they still didn’t know what they were doing. Yet despite all this, despite the fearmongering, despite the accusations of racism, despite being treated like an object for anthropological investigation by a social class insulated in its political and media bubble, the 17.4million stood firm. They did know what they were doing: they wanted to leave the EU. They wanted lawmakers to be accountable to electors. And they wanted to claw back some degree of control over their lives. And in doing so, they shattered the stale, idea-less consensus on which the political class had made its home, and struck one of the most important blows for democracy in decades. Heroes one and all.

Morrissey

Old Big Mouth might be partly responsible for some of the most thrilling pop music of recent decades, but he’s produced a lot of dross, too. ‘Lucky Lisp’? ‘Roy’s Keane’? That book? Add those to the militant vegetarianism, and sometimes Mozzer is more of a chore than a star. Yet, because he’s never been shy of speaking his mind, he can sometimes prove incredibly refreshing, too. So, this year, while the rest of the cultural firmament burned angrily with anti-Brexit sentiment, Morrissey broke ranks and declared that the vote to leave the EU was ‘magnificent’. He also attacked those who ‘refused to accept the decision of the citizens, because the result of the referendum did not benefit the regime’, singling out for particular opprobrium some Remainers’ willingness ‘to accuse, judge and convict the majority [of voters] of being racist, drunk and irresponsible’. While ‘the British political class has never quite been so hopeless’, he said, ‘the people the world over have changed’. At a time when the cultural elite has never been quite so conformist, Morrissey appears to have changed for the better. Come back, Mozzer, all is forgiven. Except ‘Lucky Lisp’.

Conor McGregor

It wasn’t difficult to see why mixed martial artist Conor McGregor picked up Irish television network RTE’s Irish Sports Person of the Year. In 2016, he became the first competitor in the history of the Ultimate Fighting Championship to win belts in two weight divisions (although the UFC later took away his featherweight title). But it’s not just his sporting accomplishments that mark McGregor out. He’s a South Dublin wit, too, delivering put-downs and micro-philosophy on demand. ‘Trash talk? Smack talk? This is an American term that makes me laugh. I speak the truth. I’m an Irish man.’ And what an Irish man. There’s no underdog embracing, no misty-eyed melancholy; what you get with McGregor is a confidently cocky, smart-dressed unwillingness to accept one’s lot in life. As he himself put it: ‘There is no opponent… You’re against yourself.’

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.