Six ways that the Miners’ Strike changed British politics forever

Thirty years on, how that uprising altered everything.

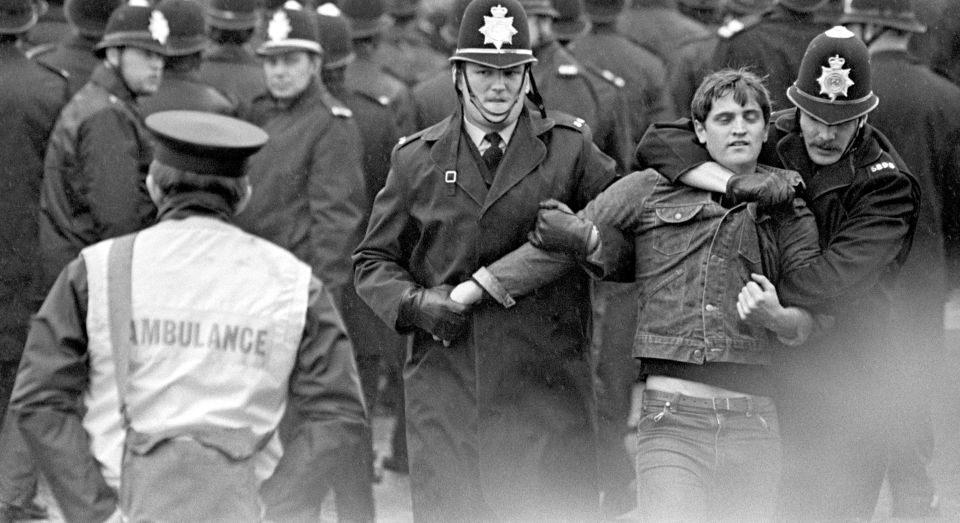

Thirty years ago today, on 3 March 1985, the year-long Miners’ Strike came to an end. Starting on 6 March 1984, it turned out to be the most important and bitter trade-union dispute in Britain since the 1926 General Strike. To defeat the National Union of Miners, UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government had to use almost every available resource, including the mass mobilisation of the police. The Miners’ Strike became the defining event of British politics in the 1980s. And in retrospect, it’s clear that it was the last class-focused dispute of its kind.

Over the past three decades, the political climate, culture and institutions that served as the background for the Miner’s Strike have fundamentally altered. Here are six things that changed enormously in the wake of that industrial conflict.

1) The defeat of the Miners’ Strike signalled the end of the era of militant trade unions

Of course, there have been industrial disputes since 1985. And some of these have displayed some of the features of traditional trade-union militancy. But the conditions that assisted the flourishing of union militancy in its real sense came to an end as a result of the socioeconomic realities of the 1980s. Trade unions had gained in strength and militancy in the context of the postwar boom. During this period of economic expansion, unions, through industrial action, succeeded in raising living standards for workers. With the end of the boom, however, there came an economic slowdown and a crisis of public expenditure. As unemployment rose, trade unions lost their power and their militant members became marginalised. By the 1990s, the British labour movement’s influence had shrunk and its institutions had been sidelined.

The trade unions of today are caricatures of their pre-1985 predecessors. They rarely mobilise or fight. Instead, they prefer to offer a variety of consumer services to their members – insurance, holidays, legal assistance in tribunals, and so on.

2) The demise of the British labour movement was paralleled by the decline of the left

The Labour Party has survived the post-1985 tumult, yes, but only by reinventing itself as the party of the middle-class, public-sector professional. Thanks to the vagaries of the electoral system, Labour can still have MPs in many of its traditional working-class seats. The decline of labourism also coincided with the implosion of the Stalinist communist movement and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In many respects, the left has been an accomplice to its own destruction. Sections of the left have been happy to distance themselves from traditional anti-capitalist and class-based politics. Lefties have reinvented themselves as environmentalists or pacifists, and have embraced a variety of lifestyle campaigns and various forms of identity politics. They have been prepared to make alliances with just about any campaign or group, from radical Muslims to backward-looking anti-technology types. In recent years, they have embraced the traditionally conservative Catholic ethos of ‘social justice’ in order to provide themselves with a semblance of ideology.

3) Paradoxically, the demise of the left has not benefited the right

Thatcherism, which was very much the dominant force during the Miners’ Strike, has lost its authority. Today’s so-called Conservatives regard Thatcher as an embarrassment and self-consciously distance themselves from her legacy. So defensive is the right today that it continually protests that it is no longer a ‘toxic brand’.

The right, like the left, has opportunistically ditched the traditions on which it was built. It has embraced a technocratic and managerial orientation through which it attempts to present itself as ‘a safe pair of hands’. In reality, the stabilisation of the political system after the defeat of the miners ended up exposing the weak moral and intellectual foundations of its authority. The sense of purpose and unity that the Thatcher government displayed in the early 1980s evaporated once the enemy against which it acted – the miners, and more broadly militant trade unionism – had been defeated. In the post-Thatcher era, the lack of authority on the right has been exposed by its failure to uphold its traditional cultural values against its opponents.

4) The collapsing influence of both the left and right has led to the end of political conflict and the rise of a clash over cultural values

Many of the political battles of the past two decades have actually been battles over cultural values, be it marriage, family, sexuality, abortion, immigration, multiculturalism, Islam or the EU. The main beneficiary of this shift from explicit political clashes to new forms of culture war has been identity politics. Identity politics constantly demands the creation of new identities and lifestyle groups, and it represents a self-conscious rejection of the political traditions of the Enlightenment.

Though identity-based groups assume various different forms and are often hostile to one another, they share something important in common: a hostility to the universalist and scientific aspirations of modernity. The focus of otherwise very different movements – from cultural feminism to environmentalism to radical jihadism – is fundamentally the same: moral regulation.

5) The exhaustion of political life has led to the expansion of regulation in everyday life

Since the Miners’ Strike, public life has been in thrall to the politics of fear. So much so that calls to ban a technology, a medical procedure or some form of speech or behaviour have served as the main source of political dispute and debate for years now. Since 1985, there has been a systematic effort to curb freedom of speech, and due process has been limited, too. As I write, academic freedom in higher education is under attack, from both officials and within the academy itself.

6) The depoliticisation of public life has nurtured a new beast: juridification

Rule-making and decision-making in all kinds of institutions are now carried out under the banner of transparency. Processes and paper trails rule private and public institutions these days. At the same time, the judiciary has been endowed with tremendous moral authority. We live in the era of the judicial inquiry. One inquest follows another, as it seems that all the important issues of the day require the verdict of a judge rather than decisions made by elected politicians. That parliamentary parties and campaigns are happy to take their lead from unelected judges is symptomatic of the disorientation of public life.

And now, 30 years after it ended, there are calls for an inquiry into certain events in the Miners’ Strike – an unwitting testament to the evacuation of political substance and democracy from public life in the three decades since that great dispute, and the corresponding birth of new forms of unaccountable cultural and judicial authority.

Frank Furedi’s First World War: Still No End in Sight is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.