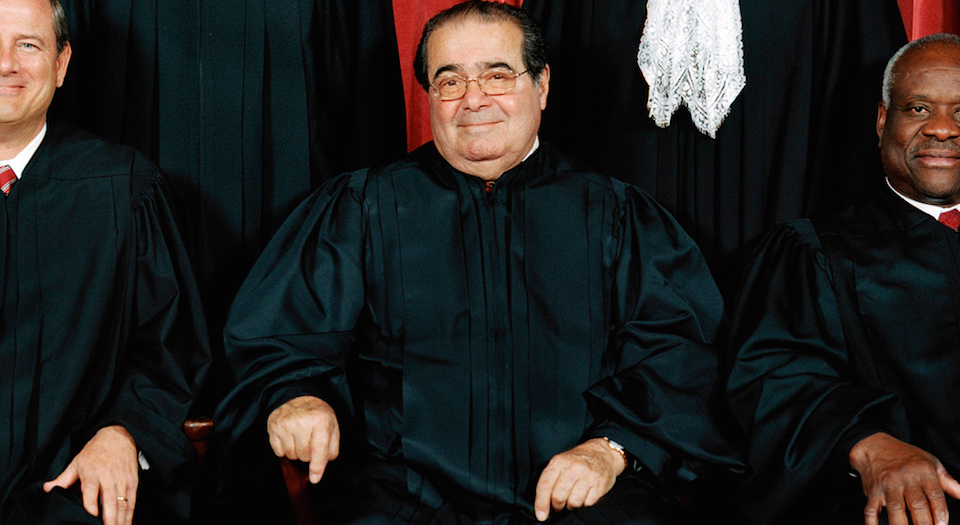

Antonin Scalia’s complicated legacy

He was a man of his principles. But he didn’t always stick to them.

Justice Scalia was America’s fiercest, most influential advocate of constitutional originalism, a theory of judicial modesty demanding adherence to the text of the Constitution and the historic notions of rights and liberty it reflected. But rhetorically, at least, Scalia was perhaps our most immodest justice, whose alternately entertaining and infuriatingly scathing dissents were nothing if not supremely self-assured.

This is an amusing irony but not a contradiction. You can have little doubt about the rightness of your own personal beliefs while abjuring opportunities to impose those beliefs on the law. Did Scalia do so? Do his opinions exemplify, not in style, but in substance, the judicial restraint, or modesty, he advocated? Not always, and his own lack of consistency in adhering to the philosophy he championed is what complicates his legacy.

He failed most dramatically to practise what he preached in considering gay rights. There are reasoned, unbiased arguments against extending federal constitutional protection to same-sex marriage (instead of deferring to the states), and Scalia referenced them in his dissent in Obergefell vs Hodges (the equal-marriage case). But given his vituperative characterisation of homosexuality in previous gay-rights cases, associating it with murder, bestiality and incest, his stated reliance on judicial restraint in opposing a constitutional same-sex-marriage right was simply not believable.

Scalia himself seemed to intuit as much, opening his dissent in Obergefell with an unconvincing and uncharacteristically defensive shrug: ‘The substance of today’s decree is not of immense personal importance to me. The law can recognise as marriage whatever sexual attachments and living arrangements it wishes… it is not of special importance to me.’

Antonin Scalia was only human after all, and as his vituperative disdain for homosexuality suggested, his impressive intellectual powers were matched and sometimes defeated by his own passionately held personal and religious moral code. Consider how his strong support for capital punishment weakened his judicial defence of it.

Concurring in a decision upholding Kansas death-penalty procedures, Scalia’s callous, cursory disregard for the horrors of wrongful convictions in non-capital as well as capital cases effectively raised more doubts about the justice system – and Scalia’s understanding of it – than it assuaged. He countered concerns about non-executed ‘exonerees’ with mere sophistry, characterising their cases as examples of the criminal-justice system’s successes, not failures. I suspect that people exonerated after spending decades in prison would disagree. And Scalia’s notorious, counter-factual assertion that opponents of capital punishment could not point to a single wrongful execution has been effectively belied by evidence strongly pointing to one in the case of Cameron Todd Willingham. Scalia’s gratuitously contemptuous dismissal of such obvious abuses did not demonstrate the judicial restraint he advocated so much as it suggested his own lack of emotional restraint.

Nor did he always successfully restrain his sectarian religious beliefs in considering the rights of other believers and especially non-believers. He was sceptical of government neutrality toward religion (mainly the proverbial Judeo-Christian religion). The principle that ‘government cannot favour religion over irreligion’ was, in his view, ‘demonstrably false’. The Constitution, he said, ‘permits disregard of polytheists and believers in unconcerned deities, just as it permits the disregard of devout atheists’. This is a questionable assertion for a constitutional originalist, and you might wonder if the devoutly Catholic Scalia would have felt differently about government ‘disregard’ for non-believers and members of minority faiths if he’d been among them.

Of course, Justice Scalia is not defined (or differentiated from other mere mortals) by his failure to adhere consistently to his own standards. And while progressives condemned him as an inflexible, hard-hearted conservative, civil libertarians should remember him more fondly.

Scalia stood for free speech in joining majorities that struck down laws banning flag-burning, animal-cruelty videos and limits on political speech, in the much-maligned (and misunderstood) Citizens United decision. He understood the thick skin and tough-mindedness that a commitment to free speech and political debate demands. ‘Harsh criticism, short of unlawful action, is a price our people have traditionally been willing to pay for self-governance’, he wrote. ‘Requiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed.’

He defended the Fourth Amendment in striking down thermal-imagery searches of private homes without warrants and GPS tracking of suspects. He confirmed the essential right of criminal defendants to confront their accusers in reversing a Massachusetts case allowing lab technicians to submit forensic reports at trial without testifying. ‘Serious deficiencies have been found in the forensic evidence used in criminal trials’, Scalia noted, not long before the FBI acknowledged having relied on faulty hair analyses for decades and technician Annie Dookhan was found to have falsified lab evidence in thousands of Massachusetts cases.

Finally, and perhaps most memorably, Scalia spoke up for habeas corpus rights in the aftermath of 9/11. In a 2004 case, Hamdi vs Rumsfeld, he opposed the Bush administration’s prolonged, summary detention of an American citizen who was designated, but not actually charged as, an enemy combatant. ‘The very core of liberty secured by our Anglo-Saxon system of separated powers has been freedom from indefinite imprisonment at the will of the executive’, Scalia wrote in a concurring opinion. In the absence of congressional action suspending habeas corpus, the government’s choice was to prosecute Hamdi, pursuant to criminal charges, or let him go.

How should we remember Scalia? Sometimes he seemed a defender of liberty and justice, and other times an apologist for repression and injustice. He leaves us a collection of sharply written, compulsively readable opinions reflecting conflicting strains of erudition and emotion, of personal engagement and judicial detachment. How should we remember Scalia? Not categorically.

Wendy Kaminer is a lawyer and writer, and a former national board member of the American Civil Liberties Union. She is the author of several books, including: A Fearful Freedom: Women’s Flight from Equality (1990); I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional (1992); and Worst Instincts: Cowardice, Conformity and the ACLU (2009).

This article originally appeared in the Boston Globe.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.