Orgreave: the last battle of a lost class war

The call for an inquiry is a useless stunt.

The unhealthy obsession with demanding an official inquiry into every aspect of Britain’s past has now spread to the miners’ strike of 1984-5. Labour leader Ed Miliband is suddenly calling for an inquiry into allegations (which everybody with a brain cell already knows to be true) of police brutality and malpractice around the Battle of Orgreave, which took place 30 years ago today.

The fact that Miliband supports it suggests that such an inquiry would be worse than useless. The fact that the Labour leader now thinks it is safe to pose as a radical on the miners’ strike also confirms that the old class war is long over – and that, having been defeated and de-clawed, workers such as the miners can now safely be patronised by elitist politicians as a lost tribe of noble savages.

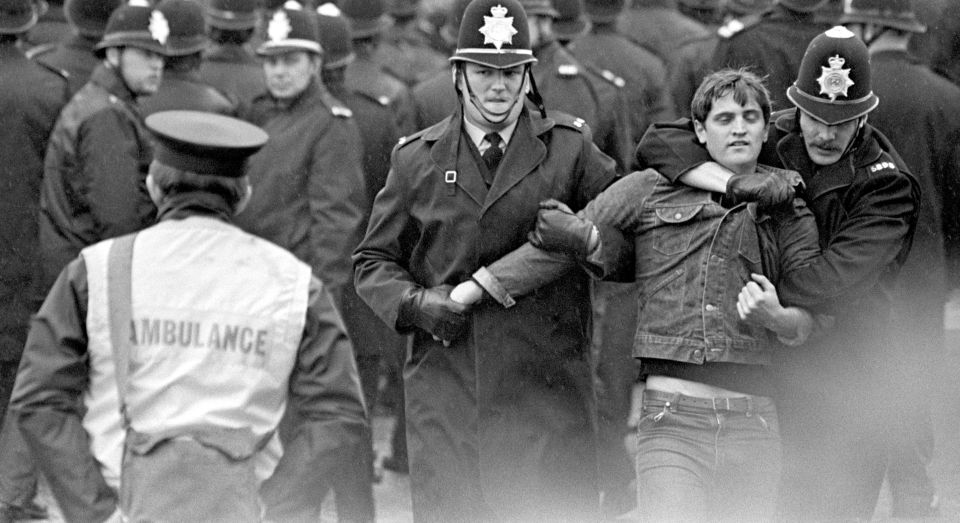

The Battle of Orgreave was a brutal and bitter clash between thousands of striking miners and an army of riot police outside a Yorkshire coke works on 18 June 1984, which left scores injured and led to 95 miners being charged with riot. (The trial collapsed amid revelations of a police and prosecution frame-up.) Demands for an inquiry into evidently pre-planned police violence at Orgreave have been growing; in November 2012, the South Yorkshire police force even referred itself to the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) over allegations of assault, perjury and perverting the course of justice by officers at Orgreave and in the subsequent court cases. The IPCC says it is still ‘scoping’ evidence to decide whether to hold a full investigation.

Now Labour leader Miliband has sought to show off his non-existent workerist credentials by joining the calls for an inquiry. Speaking to miners and members of the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign at Hatfield Main colliery in his Doncaster constituency (he is the first Labour MP to hold that seat who was not a miner or a miner’s son), Miliband praised the miners’ strike as a fight ‘for justice, for your community, for equality, for all the things that mattered. The values you fought for are the values that we have to take forward for the future.’ He added that ‘very specifically, there does need to be a proper investigation about what happened at Orgreave’.

This sounds somewhat different from the tone struck by the Labour leadership in the heat of the miners’ strike 30 years ago. The day after the Battle of Orgreave, Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher stood up in the House of Commons to support the police and blame the striking miners for what had happened, condemning the mass picket of the coking works as ‘mob rule and intimidation’. She declared that ‘giving into mob rule would be the end of liberty and democracy’, and challenged Labour opposition leader Neil Kinnock ‘forthrightly and unequivocally to condemn the scenes outside Orgreave works yesterday’. In response, Kinnock could only offer the pathetic plea that he had ‘repeatedly condemned without reservation violence by any and all parties in industrial disputes’. Thatcher was leading the armed state in an all-out class war; recently released documents show her government was willing to send the army into the coalfields. Meanwhile, Kinnock was asking why everybody couldn’t just get along and play by the rules.

What the thousands of striking miners thought of the Labour leadership’s attitude became abundantly clear in November 1984, when TUC general secretary Norman Willis addressed a miners’ rally in South Wales. The union leader made a speech attacking miners who fought back against the police. ‘Violence creates more violence’, said Willis. ‘Such acts if they are done by miners are alien to our common trade-union tradition.’ As Willis’s Thatcher-lite tirade against picket-line violence continued, a group of Welsh miners showed their appreciation by lowering a noose in front of him with a placard that read, ‘Where’s Ramsay McKinnock?’. Like Ramsay McDonald, the Labour prime minister who betrayed his party to join a coalition with the Tories in the 1930s, Kinnock was widely seen as a traitor to the mining communities.

Miliband, the managerial wonk, can hardly be said to be more left-wing or working class than Kinnock, the Welsh miner’s son. Instead, his rhetorical support for the miners’ strike as a ‘just cause’, 30 years after his party sold it out, shows that the Labour leadership now feels it is safe to pat the harmless workers on the head in a desperate attempt to consolidate the party’s disappearing core vote.

Observers have noted that Miliband’s PR team sought to highlight his statement on Orgreave this week in the immediate aftermath of the debacle over his apology for posing with the Sun’s special World Cup edition. That picture attracted particular criticism from Labour MPs and supporters on Merseyside, who still revile the Sun for its lies about the Hillsborough disaster 25 years ago. Calling for an inquiry into Orgreave was supposed to improve his image in those quarters.

Indeed, many of those demanding an inquiry into Orgreave have drawn parallels with the recent reopening of inquiries and new inquests into Hillsborough. There are some similarities – such as the leading role of the South Yorkshire police in each event, and the fact that anybody with eyes to see it has long known the truth about who was to blame for both without the need for any official inquiry. But even more striking are the contrasts between Orgreave and Hillsborough.

The Liverpool fans crushed at Hillsborough, 96 of whom died, did not go there for a fight, but to watch a football match. The only cause they were pursuing was their team’s attempt to win the FA Cup, and all that was supposed to be at stake for them was their pride and their passion. The miners attacked by the riot cops at Orgreave, by contrast, were not spectators, they were players – except that it was not a game. They went to try to close down the coking works, in the certain knowledge that there would be a confrontation with the police as there had been on every other picket line since the strike started three months earlier. The cause they were fighting for was the survival of their jobs and communities – their livelihoods and entire way of life were at stake.

For some, part of the attraction of drawing parallels is that it allows them to present the miners at Orgreave as hapless victims like the fans at Hillsborough, rewriting history in line with the victim culture of today. (In Skag Boys, his recent prequel to Trainspotting, Irvine Welsh even retrospectively portrays the heroin addiction of his central character, Renton, as a consequence of the police violence he apparently suffered as a teenager when he went down to Orgreave from Edinburgh on a coach with his dad to support the striking miners.)

But the striking miners were not just victims. They were fighters. The problem was that they were not organised enough for the Battle of Orgreave, not properly prepared to meet the police army’s force with force. Their leaders saw the mass picket at Orgreave as a symbolic stand. The other side saw it, in Thatcher’s words, as ‘mob rule’, and acted accordingly to smash it. Many of the miners did fight back, and hard, but it was too little too late. The BBC news infamously edited its film of Orgreave to make it appear that the miners charged the police lines first, rather than waiting to be attacked. Some might think, if only they had…

Orgreave became the last great battle of the miners’ strike, and of the wider class war between the state and the organised labour movement. That traditional trade-union movement was already weakened by splits and bureaucratic leadership; indeed, the miners were only picketing the coking works because the steelworkers’ union and others had failed to support their strike, using as their excuse the split in the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the refusal of NUM leader Arthur Scargill to hold a national ballot. After Orgreave, the miners held out for another nine months, though there was little chance of anything but defeat.

The Battle of Orgreave and the miners’ strike do still matter, but they shouldn’t be used to stage a mock-up rematch between the ghosts of class struggles past. The end of that era of class struggle brought on the end of the politics of left and right, which has shaped the (lack of) response to the cuts and redundancies of the latest recession.

What we need now is not another inquiry, or Miliband’s waffle about taking forward the miners’ ‘values into the future’. It would be better to rekindle their fighting spirit, for the very different battles that need to be fought today. The old class struggle may not be evident now, the working class having been defeated as an organised force and removed from the political stage. But as spiked often argues, there is a strong anti-working class, anti-popular factor in the elite’s new assaults on everything from free speech to junk food.

The real lesson to be learnt from Orgreave, which no IPCC or judicial inquiry will touch on, is about the political role of the state in controlling the masses. Thirty years ago, the state was fighting an open class war. Now the enfeebled authorities are using more subtle ways to try to nudge the public into submission. But the principle of opposing state interference to defend our liberties remains the same. Yet still the rump of the left clings to the state’s coat-tails, calling for judges and lords and quangos to fight their old battles, having learnt nothing from the bitter defeats of the past. No arm of the state should be trusted to preserve our freedoms – nor should the left hand be asked to inquire into what the right hand did 30 years ago.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, There is No Such Thing as a Free Press… And We Need One More Than Ever, is published by Societas. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).) Visit his website here.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.