No bull: in defence of artistic freedom

Let’s stand up for Hermann Nitcsch against animal-rights censors.

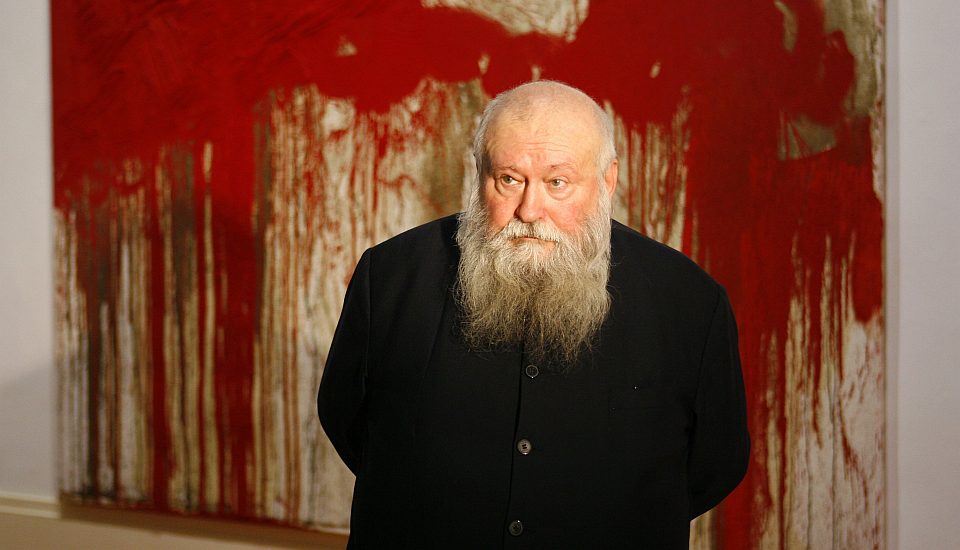

In these intolerant times, with their Safe Spaces and ritualised offence-taking, it’s good to be able to chalk up a victory for free expression. This one concerns Hermann Nitsch – a white-haired, 78-year-old Austrian who looks more like a retired theology lecturer than most people’s image of an enfant terrible, but who has been shocking crowds since the early 1960s. His habit of incorporating slaughtered animals and nudity into performance art that mimics religious rituals has over the years earned him three criminal convictions.

Nitsch’s early performances were occasionally broken up by police. But he had never had a show cancelled by a host institution until 2015, when Mexico’s Museo Jumex pulled the plug on an exhibition. The Jumex Foundation explained this as a response to ‘the political and social times’ Mexico was experiencing. However, as the New York Times reported, there was speculation (denied by Jumex) that a 5,000-strong petition by animal-rights activists may have swayed the decision.

Two years later, Nitsch’s show, 150.action, due to be staged in June at the Dark Mofo festival in Hobart, Tasmania, also came under fire from animal-rights activists. Described as a ‘bloody sacrificial ritual’, the show reportedly involves nudity, a dead bull and 500 litres of blood.

Members of Animal Liberation Tasmania collected over 19,000 signatures calling for the banning of 150.action on the grounds that it ‘trivialises the slaughter of animals for human usage and condemns a sentient being to death in the pursuit of artistic endeavours’. The RSPCA weighed in, too, with Peter West, head of RSPCA Tasmania, telling the Guardian that the event ‘is clearly not respectful’.

In truth, the moral case for restricting Nitsch’s artistic freedom was shaky at best. If the bull was going to be tortured it would be a different matter. But, as Leigh Carmichael, Dark Mofo’s creative director, made clear: ‘There will not be a live animal slaughtered as part of any Dark Mofo performance.’ The animal chosen is on the market for slaughter and will be locally sourced and humanely killed at a local abattoir. After the event the meat will be eaten – at least if health-and-safety laws can be satisfied. Nitsch himself has called factory farming ‘the biggest crime in our society’. At times, the event’s description sounds more like an advert for an organic restaurant than an orgiastic ritual.

While this may not satisfy those who think that the killing of any sentient being is wrong, it’s hardly likely that all 19,000 signatories are vegans or Buddhists. And anyone less strict must accept that, if we want to use any animal products at all, this means breeding excess males that it is practically impossible to keep.

As for being ‘not respectful’ to the animal, who’s to say what’s respectful? Dark Mofo has always had pagan undertones and Nitsch is obviously sincerely dedicated to his art and interested in pagan practices. Genuine pagan sacrifice is usually considered to have been respectful to animals, which after all were offered to a God. Would campaigners be so keen to ban this if it was a genuine minority religious practice?

Despite all this, early indications were that Hobart City Council might ban the event. Hobart’s lord mayor, Sue Hickey, reportedly condemned the performance and the council voted unanimously to accept the petition – said to be its largest in over 20 years. However, according to a recent report in the Smithsonian magazine, the Tasmanian government has decided to let 150.action go ahead. In a rare show of restraint from a politician, Tasmanian premier Will Hodgman said: ‘I don’t believe it’s a good place for politicians to be in, to be making judgement calls about art, no matter how confronting it is.’

Should we care? It’s hardly surprising to learn that Nitsch divides opinion. Alexander Adams, writing on spiked after the cancellation of the Museo Jumex performance, described his art as ‘generally ill-judged, often pretentious’. A more sympathetic critic might note Nitsch’s longstanding interest in religious art. With his reliance on a palette of gaudy reds and blacks and his reduction of the body to meat – in paintings like ‘Entombment’, for example, where Christ and his disciples appear as anatomical drawings under a wash of blood – he seems to be exploring similar ground to his older contemporary, Francis Bacon. At the very least we should recognise his sincerity: how many of the Young British Artists would risk prison for their art?

The real reason to care, though, is that it’s becoming increasingly hard for local authorities to face down well-organised activists who generate tides of online outrage expressed in fat petitions. The temptation for a bit of cheap virtue-signalling often proves too great. Every time a facedown is successful, then, we should celebrate. We should also remember that artistic freedom, like freedom of speech, is vital to free societies. Generations have confronted suffering and danger to secure it; it shouldn’t be discarded lightly. And just as freedom of speech means freedom for all speech, so artistic freedom means freedom for the art we hate as much as the art we love.

Rupert Cogan is a writer.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.