Ali: a fighter, not a luvvie

Without his boxing brilliance, he could never have 'shook up the world'.

To judge by many of the eulogies to Muhammad Ali in the run-up to his funeral tomorrow, you might be forgiven for forgetting that he had ever set foot in a boxing ring.

Instead Ali has been hailed as ‘the civil rights and anti-war activist’, a ‘champion of social justice’, as somebody has tried to attach The Greatest to every passing right-on cause. One BBC football commentator even fantasised about how much Ali would have appreciated the investment made in English women’s soccer. It is a wonder nobody has tried to claim Ali would have backed the Remain campaign had he lived.

Media and political luvvies who normally recoil in horror from the brutality of ‘barbaric’ boxing have been falling over one another to beatify the ‘beautiful’ Ali, as if he was something apart from his sport. They come to bury Ali the boxer, not to praise him. As Madonna put it, tweeting for the massed ranks of celebrity mourners, ‘This Man. This King. This Hero. This Human! Words cannot express. He shook up the World! God Bless Him.’

Are these people sure they have got the right funeral? It might be true, as they all say, that Ali ‘transcended boxing’ and was elevated into a global symbol of struggle. But without the boxing, we would never have heard of him.

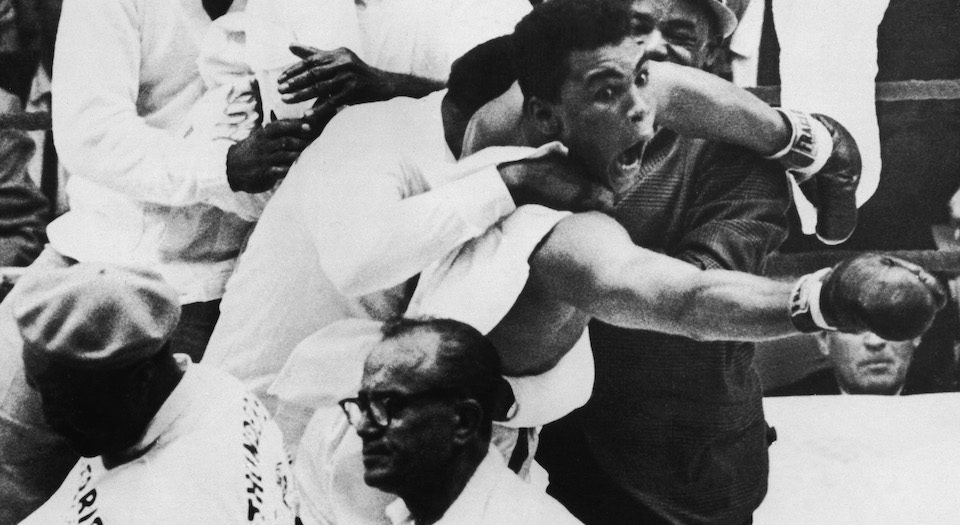

Ali did not become the best-known face on the planet because of his looks, or his poetry, or his religious beliefs, or his opposition to the Vietnam War. He became the most famous man on Earth for winning the world heavyweight championship three times, for the Rumble in the Jungle and the Thrilla in Manila. For his unparalleled brilliance at committing acts of stylised violence in a boxing ring.

It was boxing that made Ali and made us notice him. He certainly projected a different image of the sport than the champions who preceded him, winning new fans to the ‘sweet science’ of boxing with his cool dancing style and the ‘Ali shuffle’, like James Brown in boxing gloves. But Ali’s much-lauded ability to ‘float like a butterfly’ would have scored no points without the punchline ‘sting like a bee’ — or more accurately, like a hornets’ nest.

Because make no mistake, as Rob Lyons noted on spiked earlier this week, when he needed or just wanted to be, Ali was brutal. Some of his great Seventies fights were bloodbaths. His third and final bout against Joe Frazier, the aforementioned 1975 Thrilla in Manila, is widely considered the greatest heavyweight title fight of modern times. It was no place for butterflies. By the end of it Frazier was blind in both eyes (but still trying to fight until his corner threw in the towel before the final round), while Ali was preparing to die.

And Ali was not always the winsome, witty clown king or champion of humanity depicted this past week. This contradictory character (aren’t all the best ones?) could also be vicious and vindictive to opponents, especially when as a young man he felt they had insulted him or his faith. In 1965, Floyd Patterson was put up as the ‘white man’s nigger’, to take the title back from Ali the ‘un-American’ Black Muslim. Ali told a reporter that Patterson was ‘a deaf-dumb so-called negro who needs a spanking. I plan to punish him for the things he’s said, cause him pain.’ And he did. Two years later, in the run-up to their 1967 title fight, Ernie Terrell insisted on calling the ‘anti-American’ champion Cassius Clay — Ali’s ‘slave name’. Ali beat Terrell mercilessly for 15 rounds, repeatedly screaming ‘What’s my name?’ into his opponent’s battered face, in a display that horrified the refined sporting commentators of the BBC.

It was the boxing ring that became the platform for everything else that Ali did and said. Without it the ‘Louisville Lip’ would have been one more loud-talking angry black American, and who would have listened? Even his courageous stand in refusing to fight in the Vietnam War only made headlines because it was made by the greatest professional fighter on the planet. Everybody from Barack Obama downwards has seemed keen this week to spice up their Ali tributes with his own famous words, ‘I shook up the world!’. We might recall that Ali was not talking about civil rights or world peace when he said that. He was shouting into the media microphones in a frankly manic state, with blood on his hands and in his eye, having just won the world title by defeating the fearsome Sonny Liston.

Ali the champ has been done a disservice in death by those boxing-loathers who want to downplay the importance of pugilism in his life. In the process of trying to paint Ali as a saintly somebody else, some have also sought to ignore those of his views – on the role of women, say, or homosexuality – that jar like an Ali jab with the prevailing consensus today. We have even been subjected to media reporters sanitising his most famous (though possibly apocryphal) quote as, ‘No Vietcong ever called me the n-word’. Perhaps we should just be grateful that Ali was beyond the influence of these sanitisers in his prime.

(Not every celebrity Ali fan fits into that category. Some great writers followed him through his career — such as Norman Mailer, whose book The Fight, on the Ali-George Foreman Rumble in the Jungle, reveals more about The Greatest than all the sugar-coated tributes heard since his death.)

While praising Ali’s life as something other than a boxer, many would now like to turn his decline and death into an argument against boxing. But it was boxing that made Ali, and made the world sit up and take notice. It was ultimately because of what he did in the boxing ring 40 or 50 years ago that some of us still have Ali posters at home, and will always remember him.

At some sporting events in the UK this week, crowds paid tribute by chanting ‘Ali, Bomaye!’, the words made famous by the people of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) at the defining moment of his career, when he proved he was The Greatest and won back his title by knocking out the ‘invincible’ Foreman in the 1974 Rumble in the Jungle. It means not ‘What a Human!’, but ‘Ali, Kill Him!’.

It might be stretching a point to suggest that Ali was a fighter, not a lover, given his famous appetite for women. But unlike some of his louder posthumous cheerleaders in both the mainstream and social media, he was no pacifist luvvie. We should not let them bury the red-blooded history of Muhammad Ali, the boxing immortal.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. The ‘concise and abridged’ edition of his book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by William Collins.

Picture by: Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.