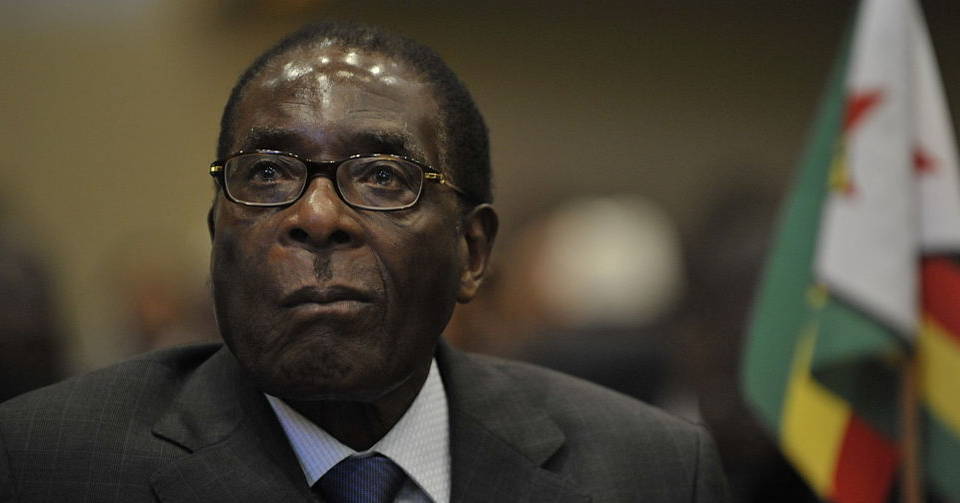

Mugabe: no longer the Hitler of Africa?

In 2008, Mugabe was the West's No1 bogeyman. In 2013, no one cares.

At the weekend, 89-year-old Zanu-PF leader Robert Mugabe was re-elected as president of Zimbabwe. He has now been in power since Zimbabwe was founded over 30 years ago – this after he helped lead the liberation struggle during the 1970s against Ian Smith in what was the former British colony of (Southern) Rhodesia.

But what is remarkable about this election victory is not the further evidence it supplied of Mugabe’s indefatigability – although it’s worth remembering his peers in the African liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s have long since departed the scene. No, what is remarkable about it is just how muted the international response has been. There have been a few mournful editorials in Western newspapers, a few politicians decrying the result, but there has been no venting of righteous spleen, no wall-to-wall outpourings of anger and pity.

Five years ago, things were very different. In April 2008, it emerged that Morgan Tsvangirai, the leader of the Movement for Democratic Change (or at least one faction of it, MDC-T), had beaten Mugabe in the presidential elections. Unfortunately for Tsvangirai and the MDC, following a recount, they had seemingly not won enough seats (allegations of vote-rigging were rife) for an overall victory. So, with another election planned for the summer, Mugabe’s forces launched a campaign of violence and intimidation against the MDC and Tsvangirai (who was arrested in June 2008), in a bid to avoid a repeat of the first election.

The international response to Mugabe’s crackdown and electoral chicanery in 2008 was pronounced in volume and ire. Western commentators issued condemnations, reports sought to tug on the heartstrings, and politicians threatened further sanctions. This was hardly a surprise, of course. Although the News of the World had first dubbed Mugabe the ‘black Hitler’ in 1978, he had been seen as something of a liberationist hero during the 1980s. During the course of the 2000s, however, he was thoroughly transformed into the whipping boy of Africa, a one-man conduit for all that was seemingly rotten about this uppity, post-colonial continent. So when he appeared to be on the ropes, lashing out at his own people in a desperate attempt to cling to power, the opportunity was too good to miss for posture-hungry politicians looking for a stage on which to invent and demonstrate their moral authority and, in the process, take Zimbabwe’s affairs out of the hands of Zimbabweans.

The prime movers in the demonisation of Mugabe were the predictable figures of US president George W Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair, later to be followed by the lumbering fist of his successor Gordon Brown. From the early 2000s onwards, criticism of Mugabe as ‘corrupt’ and ‘criminal’ was accompanied by a harsh regime of economic sanctions which plunged Zimbabwe into an economic abyss. By 2008, GDP was negative, unemployment was running at 80 per cent, and inflation at 100,586 per cent. Yes, Mugabe’s determination to strip Zimbabwe’s remaining white farm owners of their land throughout the 2000s didn’t help agricultural productivity; but the root of Zimbabwe’s economic problems could be traced to the external sanctions regime, not internal land redistribution.

The election year of 2008, then, could be seen as the culmination of Mugabe’s and, effectively, Zimbabwe’s demonisation by Western leaders. Mugabe himself was the baddest of bad guys, and Tsvangirai, who had taken to touring the world canvassing support following the March 2008 elections, was the goodiest of good guys. This was the black-and-white vision which, trained on Zimbabwe, transformed the political struggles and fighting there from a matter for Zimbabweans into a simplistic tale of good and evil for Western audiences. And it was a narrative which dominated newsprint and political discourse for months during 2008 – until a power-sharing agreement was signed in September, which left Mugabe in situ and instated Tsvangirai as prime minister.

But Zimbabwe 2013 is a different matter. The weekend’s elections have prompted little interest, let alone outrage in the West. Why? What has changed? Mugabe is still there, of course, as is his would-be nemesis Tsvangirai. Economic sanctions have been relaxed a bit, and the economy has grown slightly, but unemployment is still running at over 80 per cent, and inflation remains a massive problem. Moreover, despite the head of the election-observing African Union, Nigeria’s Olusegun Obasanjo, a good friend of Mugabe, approving the Zimbabwe poll, allegations of vote-rigging persist, from the use of electoral lists featuring hundreds of dead people to the ferrying in of Zanu-PF supporters into MDC strongholds.

Yet despite the persistence of the very things which seemingly piqued Western politicians and pundits five years ago, the noisy condemnation has all but disappeared. Indeed, the moralising, the simplifying and the righteous posturing have been as absent this time round as any frontpage coverage. Admittedly, US secretary of state John Kerry has said that he doesn’t think the election result is a genuine expression of the will of the Zimbabwean people, and UK foreign secretary William Hague has said he has grave concerns, too. But their statements lack the conviction of their predecessors’ declamations five years ago.

In fact, this time round there has been handwringing about the lack of handwringing. The moral narrative, the tale of good vs evil in Africa, has got lost en route, it seems. One Australian commentator bemoaned Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd’s silence this time, when back in 2008 he was right there to the fore, slamming Mugabe alongside Bush and Brown. Mark Malloch Brown, a minister under Brown, writes in the Financial Times: ‘Zimbabwe’s election demonstrates a dangerous trend. If bullets do not fly and heads are not broken, many outsiders, notably neighbours, are happy to declare with relief that the poll appeared broadly free and fair.’

But it’s not just the absence of bloodshed or bullet-holed drama that has led to the lack of Western interest in Zimbabwe’s elections. There is something else going on, too, something that has thankfully shifted and broken the black-and-white moral frame through which Zimbabwe had been transformed into an object for international intervention in the recent past.

Of course, one reason for this is that the elevation of Mugabe into an all-purpose hate figure in the West could not be sustained interminably. Since 2008, other tin-pot dictators have assumed Mugabe’s mantle, from Colonel Gadaffi in Libya to the rather more powerful Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Mugabe, the long-time bête noir of Bush and Blair, has been replaced in Western leaders disaffections by other Really Bad Guys, Doing Really Bad Things. New stages have been found for the kind of shallow good-vs-evil posturing so beloved of contemporary political leaders.

More importantly perhaps, changes within Zimbabwe itself have rendered it an unsuitable stage for striking moral poses. The illusion of a black-and-white struggle has become tainted by the greys of reality over the course of the past five years. For a start, Tsvangirai and the faction-ridden MDC were not boosted by having a seat at the top table after 2008; they were compromised by it. The MDC became part of the problem. For instance, taking responsibility for health and education, MDC ministers were criticised within Zimbabwe for their failure to deliver on their promises. As one observer wrote earlier this year, ‘Today the party [MDC] is more dysfunctional and commands less authority and support than ever before, and it shouldn’t come as a surprise when it loses, even in a free and fair election.’

Tsvangirai himself has suffered something of a fall from grace, too, no doubt helped on the way down by Mugabe and his cohorts. Stories of love affairs, and illegitimate children, not to mention his lavish lifestyle, have filled the pages of Zimbabwe’s popular press. Tsvangirai’s problem wasn’t public sanctimony about his behaviour; it was an increasing public scepticism about his judgment. As the Zimbabwe Independent put it in September 2012: ‘This argument [that Mugabe set Tsvangirai up] is not sustainable because it wholly ignores the issue of Tsvangirai’s character and judgement. It also presupposes he was not an active participant in all these affairs. Yet it is clear he has been involved by choice.’ As ZANU-PF’s Jonathan Moyo said, Tsvangirai approaches every issue with a shut mind, and every woman with an open zip.

In the UK, even the Telegraph, which has opposed Mugabe since he overthrew Ian Smith’s colonial regime in the 1970s, has lost faith in the Tsvangirai. ‘His period in office – if not in power – showed up all his shortcomings’, wrote one Telegraph commentator: ‘A few MDC ministers made an impact, but Tsvangirai personally made almost none… Tsvangirai is a man of many qualities, but he has failed as a politician. He should have the wisdom to admit as much – and to leave the scene with honour.’

But the compromising and seeming corruption of the MDC and Tsvangirai is not the only reason for the collapse of the sanctimonious consensus of a few years ago. And here we come to the unpalatable truth for Western poseurs: Mugabe still commands large swathes of popular support in Zimbabwe, especially in rural areas. Not only that, but the constant assaults from the likes of Blair and Brown actually played to Mugabe’s rhetorical strengths. That is, he has always been adept at playing the national liberation leader, at playing up the continued anti-colonial struggle. ‘If standing for my people’s aspirations makes me a Hitler’, he once said, ‘let me be a Hitler a thousand times’.

More recently, Mugabe’s big plan – to ‘indigenise’ foreign-owned companies, compelling them to hand over at least 51 per cent of shares to local Zimbabweans – exploited anti-Western sentiment, and affirmed his anti-colonial credentials. It was a move that reportedly went down very well with Zimbabwe’s largest electoral constituency: the unemployed. Indeed, in early 2012, voter surveys from Afrobarometer and US-based pro-democracy group Freedom House indicated what last weekend’s election seemed, at least on the surface, to prove: that many Zimbabweans now prefer Mugabe to Tsvangirai. Back in 2009, Freedom House found that just 12 per cent would back Zanu-PF compared with 55 per cent who said they were behind MDC. Three years later, 31 per cent said they would back Zanu PF ahead of just 19 per cent for MDC.

And this, ultimately, is why there is so little handwringing in the West this time round. The moralising, black-and-white narrative spun by Blair, Bush Brown et al has unravelled. Reality has simply proved too complex and too unpredictable for such a simplistic framework to contain. Of course, the situation in Zimbabwe was never as clear-cut as was made out throughout the 2000s, when calls for further intervention and economic sanctions were at their height. Yet that turbidity and complexity was effaced by the rather narcissistic desire to be seen to be doing good: ‘We’ve beaten Mugabe’, ran the Evening Standard front page in April 2008. As it turned out, they’d done nothing of the sort.

Sadly, however, that moralising approach, which turned Zimbabwe’s domestic political situation into an international affair, has not been shattered for good; rather, it has merely shifted its focus elsewhere, to other countries that are now being screwed up by simplistic, self-serving Western attentions. The lessons of Zimbabwe are yet to be learned.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.