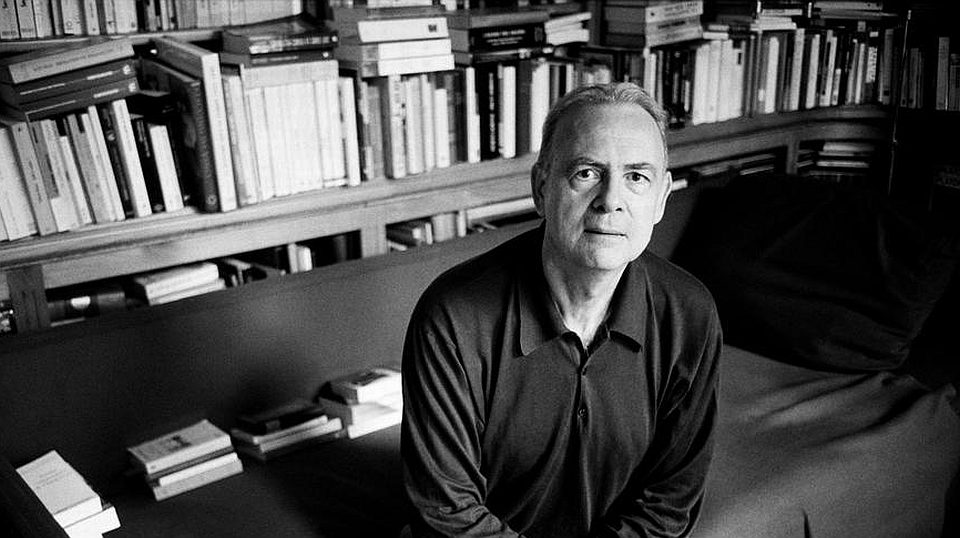

Modiano: master of the oblique

This translated collection will bring the French writer's sparing prose to a new audience.

The Nobel Prize for literature is an annual occasion for the average person to feel parochial and uncultured. In a good year, a laureate might be a writer you’ve heard of – perhaps even read – but confronted with a Swedish poet or Chinese novelist who has never had his writings translated into English, one cannot be blamed for simply shrugging and forgetting the name.

Patrick Modiano is a name that is unlikely to have meant much to Anglophone readers before 9 October 2014, when he was announced as recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Fewer than half of his novels, novellas and memoirs have been translated from his native French into English and most of those are now out of print. Previously, he was best known outside of France through his work on the script of the Louis Malle film Lacombe, Lucien (1973).

A newly published collection of three of Modiano’s novellas in English gives English-speaking readers the chance to assess the 2014 laureate. Suspended Sentences contains: ‘Afterimage’ (‘Chien de printemps’), ‘Suspended Sentences’ (‘Remise de peine’) and ‘Flowers of Ruin’ (‘Fleurs de ruine’). The translator, Mark Polizzotti, has endeavoured to keep the prose clear and uncomplicated as the original. In that aim he has succeeded. The prose is light and direct, completely lacking any irritating density and tricksiness. The text is broken into short sections, sometimes shorter than a page. Modiano does not linger on detailed descriptions and keeps the action moving.

‘Afterimage’ is a tale about an adolescent boy who volunteers to help a mysterious photographer called Jensen. Jensen is absent much of the time and what little the narrator knows of him is pieced together from incomplete and oblique memories. Jensen is a charismatic photojournalist colleague of Robert Capa. He is inexplicably casual about his photography collection and seems both troubled and secretive. A woman called Nicole calls at the apartment, constantly missing Jensen and leaving urgent messages for the narrator to pass on. Nicole’s jealous husband, who menaces the narrator and Jensen, is an absurd and threatening presence on the street outside Jensen’s apartment. There is a palpable sense that the narrator feels distanced from the significance of what he has witnessed, as if he is locked outside of his own experiences. All of the novellas are narrated retrospectively in the first person.

‘Suspended Sentences’ recalls a boy’s life in the postwar Paris suburbs, raised by a motley band of individuals that only in hindsight does he realise are criminals. As children do, he remembers the people through incidental aspects: the books they gave him, the fancy American car that so impressed him, their distinctive clothing. He and his brother have been left in the care of the ‘Rue Lauriston gang’ by his absent parents, a mother who is a touring actress and a father who is a travelling businessman. The narrative, which covers only a year in the narrator’s childhood, is not meant as a sustained narrative, more a series of vivid images and memories associated with a peculiar interlude in a child’s life.

‘Flowers of Ruin’ is a type of noir crime thriller, albeit an oblique one. The narrator seeks to piece together the final night of a couple who commit murder-suicide together in 1933 following an orgy. The narrator begins deducing elements of their story from reading press reports. Who were the four people that the normally staid couple met on their last evening? Why does the waiter, who witnessed the couple’s evening, lie about their movements? What is the involvement of the man who calls himself ‘Pacheco’, who claims to be minor nobility and denies being a collaborator? Some of the characters overlap with the other novellas, tempting readers to compare.

In the background lurks the experience of the German occupation of Paris and the deportation of the Jews. The fear, loss and deception of that period pervades the lives of the characters in all of these novellas. Much of this comes from Modiano’s own life (he was born in 1945 to a French-Jewish family). That historical context is integral to the plots and settings of these stories and does not feel overtly political or polemic. There are social and personal ramifications hinted at but not developed in these short novellas.

Perhaps some readers may find the references too oblique and the exposition too scant to make these novellas satisfying in conventional ways. Yet the very resonance of the novellas resides in the way Modiano resists supplying easy solutions or proposing a didactic position. The Nobel laureateship has drawn attention to a writer whose work is engaging and thought-provoking, yet accessible enough to appeal to readers who don’t tend to consume high literature.

Perhaps next year, Ismail Kadare will finally win a Nobel Prize and get the sort of attention Modiano is now deservedly receiving.

Alexander Adams is a writer and art critic. He writes for Apollo, the Art Newspaper and the Jackdaw. His book The Crows of Berlin is published by Pig Ear Press. (Order this book from Pig Ear Press bookshop.)

Suspended Sentences: Three Novellas, by Patrick Modiano, is published by Yale University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.