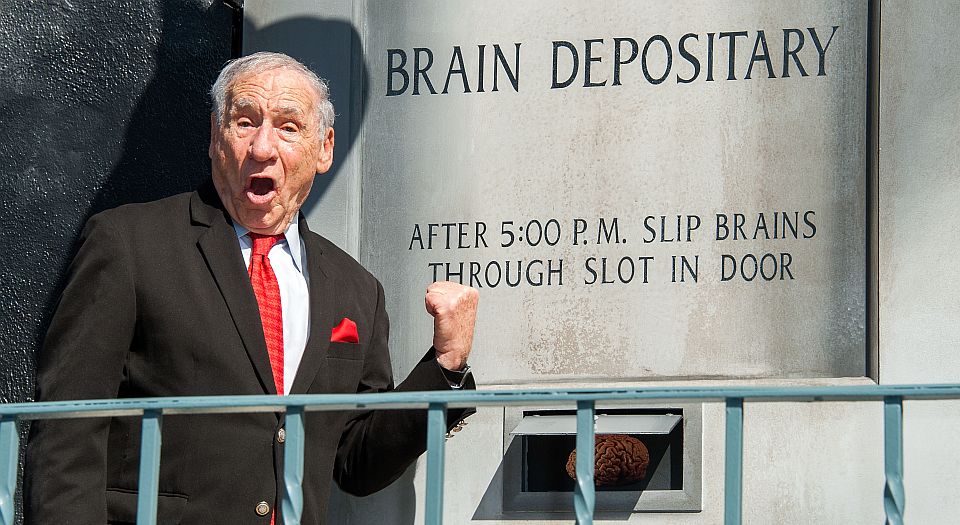

Mel Brooks and the philistinism of PC

Think edgy material has no place in comedy? Watch Blazing Saddles.

The great Mel Brooks has said that Blazing Saddles, his risqué 1974 cowboy comedy, would never get made today. ‘We have become stupidly politically correct, which is the death of comedy’, he told Radio 4, while promoting the new Young Frankenstein musical. ‘It’s okay not to hurt the feelings of various tribes and groups. However, it’s not good for comedy. Comedy has to walk a thin line, take risks. Comedy is the lecherous little elf whispering into the king’s ear, always telling the truth about human behaviour.’

When the 91-year-old was asked where he himself drew the line, he said he ‘would personally never touch gas chambers or the death of children or Jews at the hands of the Nazis’. This is clearly his own personal choice, however, and not a dogma he wants to apply to all. And as many pointed out on Twitter, as the usual suspects went into meltdown about Brooks’ ‘reactionary’ comments, Brooks is not only Jewish – he actually fought the Nazis. In any case, hearing a comedy great take on today’s uptight culture reminds us what we might be missing out on.

Blazing Saddles stars Cleavon Little as the black sheriff of a racist town in the Old West. His sidekick is the Waco Kid, played by Gene Wilder. It was a huge success at the time, and remains a touchstone of film comedy. But it also uses racial epithets pretty liberally. The idea of it is unimaginable today. But as Brooks points out, it’s what makes the film so potent, and funny. ‘Without that, the movie would not have had nearly the significance, the force, the dynamism, and the stakes that were contained in it.’

A big part of Brooks’ anarchic comedy lies in subverting the most familiar generic tropes, such as the musical (The Producers) or horror flicks (Young Frankenstein). These films are both tributes to these beloved genres and an interrogation of the politics therein. Blazing Saddles upends the traditional place of black people in Western films. Sheriff Bart is not only set against the racist inhabitants of Rock Ridge, but the entire history of the genre. He becomes an archetypal hero on very different terms.

The fact that Blazing Saddles might not be made today reminds us of the philistinism of our times. There’s a strange paradox at play: the very people who insist that racism is everywhere also want to scrub out any reference to it, past or present. Even a film that portrays racism negatively is seen as suspect. Racial slurs, uttered by villainous characters, still poison the story. And this doesn’t just go for comedy. Even great, anti-racist works of literature, like Huckleberry Finn, have been criticised for their use of the n-word.

In rankling at these works’ provocations, people miss the profundity. Gross-out humour was the bedrock of Nineties popcorn comedy, but those films were devoid of substance. That’s part of the reason they’ve aged terribly. Meanwhile, the great controversial satires – like Monty Python’s blasphemous Life of Brian or Chaplin’s Hitlerian tale, The Great Dictator – have endured, even if they’re not as gut-wrenchingly hilarious as they were in their day. And they all had a humanistic pay-off, whether it was Chaplin’s closing monologue or ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life’.

Brooks’ films (well, the good ones) have stood the test of time because they’re driven by more than shock value. They see so much wrong with the world, and depict it with brutal honesty, but they are essentially optimistic about their characters and their capacity for shared humanity. By the end of Blazing Saddles, the whites of Rock Ridge unite with the black and Chinese railway workers to construct an exact replica of their town in an effort to save it from a corrupt politician. The plan is ridiculous, but it makes a subtly utopian point.

It’s worth noting that the decline of controversial comedy goes hand in hand with a new snobbishness. Take SNL or John Oliver. Comedians today think saying something political makes them both funny and sophisticated. The reason they are neither is because they don’t challenge their audiences – they comfort them. They tell them that Trump (or before him, George W Bush) is a moron, and We are better than him. Conveniently for comedy writers, this takes little effort or originality, which is why the political-comedy schlock being made at the moment will (thankfully) soon be forgotten.

Brooks’ work isn’t about passive engagement. He never set out to please his audience by flattering their smug morality. He challenged both their sensibilities and their assumptions about cinema. His constant breaking of the fourth wall was in the tradition of Brechtian alienation, forcing the audience to contemplate the film’s construction. And he forced us to confront our dark history, in the most ridiculous way possible. As popular culture grows evermore complacent and censorious, we need the inventive, incendiary spirit of Mel Brooks more than ever.

Christian Butler is a spiked columnist. Follow him on Twitter: @CPAButler

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.