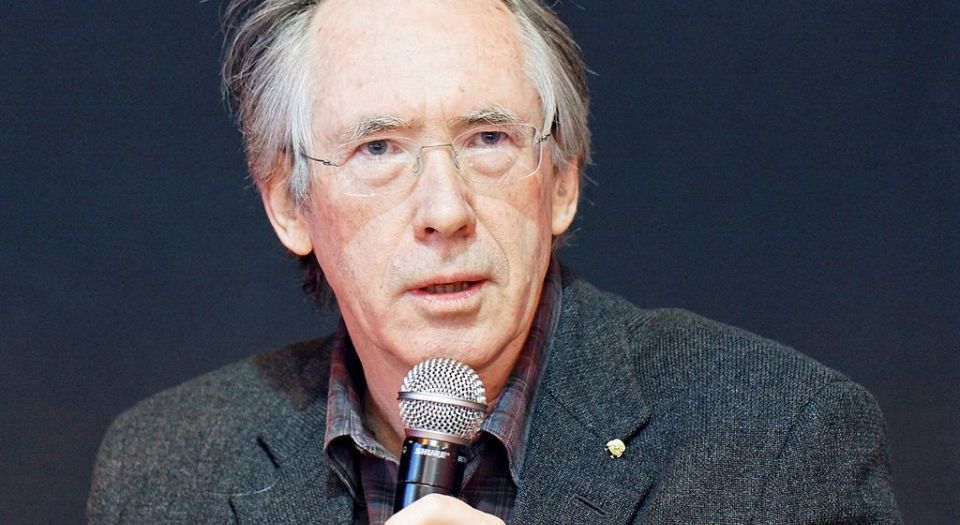

Ian McEwan: a lapsed rationalist

The Children Act lays bare the limits of the scientistic worldview.

The publication of Ian McEwan’s latest novel, The Children Act, was certainly timely. While the British media became increasingly fixated on the fate of Ashya King, the little boy with cancer at the centre of a custody battle between the state and his Jehovah’s Witness parents, McEwan seemed to have written a novel with uncanny similarities: Fiona Maye, a family court judge, must decide whether the state should force Adam Henry, a teenage leukaemia sufferer on the brink of death, to have a blood transfusion despite it being against his and his parents’ Jehovah’s Witness beliefs. So far, so serendipitous.

Yet, if taken at the level of this central narrative, which unfolds against the background of Fiona’s disintegrating marriage to her sex-seeking academic husband, Jack, The Children Act will appear shallow, complacent, the work of an author too comfortable in his beliefs even to imagine what doubt feels like. Because what should be a profound moral and political dilemma, a decision drenched in nighttime sweat, is presented by McEwan in almost black-and-white terms. The Henrys’ faith is painted in dark, illiberal colours: anti-gay, anti-abortion, anti-wanking. McEwan, with a gift for the ironising metaphor, even likens religion to the ‘group delusion’ of Satanic-abuse hunters of the 1980s – state agents who wanted to take children away from their parents.

Fiona’s, and no doubt McEwan’s, Godless, rationalist worldview, infused with science and a dollop of utilitarianism, is painted in all too favourable terms. There’s simply no question that she is right: Adam must not become a ‘martyr to his faith’. As a newly Godless Adam himself admits to Fiona in the latter section of the novel, her judgement had made everything ‘collapse into truth’: ‘It was like a grown-up had come into a room full of kids who are making each other miserable and said, Come on, stop all the nonsense, it’s tea-time!’, he tells her. ‘You were a grown-up.’

There’s no tension here, no moral drama. A ‘beautiful’, ‘innocent’ boy, ‘with crescents of bruised purple fading delicately to white under the eyes’, and a near-enough sublime poetic, musical talent, is always going to be saved by the better judgement of Fiona, who embodies not just the law, but reason, good sense – and every belief and prejudice holding sway today. The status quo couldn’t ask for a more affirmative novel from McEwan.

Or it couldn’t if that was all The Children Act amounted to. But fortunately, there’s something more interesting going on here. McEwan is certainly a secular rationalist with an inclination towards the scientistic. So a description of London’s wet weather quickly becomes a chance to rehearse a bit of climatology: ‘The jet stream was broken, bent southwards by factors beyond control, blocking the summer balm from the Azores, sucking in freezing air from the north. The consequence of melting manmade climate change, of melting sea ice disturbing the upper air, or irregular sunspot activity that was no one’s fault, or natural variability, or nature’s rhythms, the planet’s lot.’

At another point, McEwan, recalling Fiona’s judgement on the case of conjoined twins who needed one to die for the other to live, turns to biology for an explanation as to why things turn out as they do:

‘She saw in the remembered pictures of Matthew and Mark a blind and purposeless nullity. A microscopic egg had failed to divide in time due to a failure somewhere along a chain of chemical events, a tiny disturbance in a cascade of protein reactions, a molecular event ballooned like an exploding universe, out on to the wider scale of human misery. No cruelty, nothing avenged, no ghost moving in mysterious ways. Merely a gene transcribed in error, an enzyme recipe skewed, a chemical bond severed. A process of natural wastage as indifferent as it was pointless. Which only brought into relief healthy, perfectly formed life, equally contingent, equally without purpose. Blind luck to arrive in the world with your properly formed parts in the right place, to be born to parents who were living, not cruel, or to escape, by geographical or social accident, war or poverty. And therefore to find it so much easier to be virtuous.’

As the Darwinian refrain of McEwan’s Saturday runs, ‘There’s a grandeur to this view’. As well there might be for McEwan. But this sometimes cosmic, sometimes microscopic, view of the world, so widely reiterated today, in which human agency is a mere illusion, and human drama a triviality, also proves problematic for McEwan. He might agree with it, but he can’t sustain it in the context of a novel which, after all, depends upon character and narrative, upon agency and drama. His ideas about the world tend one way, his art, his fiction, tend the other.

So something else emerges, something troubling, something disconsolate. After all, if everything that exists is naturally determined, but entirely random and arbitrary, then where is the meaning, where is the point to it all? Where indeed is the story, the authorial judgement? Nothing much matters, as Fiona herself momentarily concludes as she looks at Adam on his voluntary death bed and ponders what would follow his death: ‘Profound sorrow, bitter regret perhaps, fond memories, then life would plunge on and all three would mean less and less as those who loved him aged and died, until they meant nothing at all. Religions, moral systems, her own included, were like peaks in a dense mountain range seen from a great distance, none obviously higher, none more important, truer than another. What was to judge?’

The grand vistas of science, the near-cosmic perspective they grant McEwan, reduce humanity to a naturally occurring phenomenon. And here is the twist to The Children Act: the Godless world, unfolding in its unfathomable entirety according to physical laws still beyond our comprehension, is found wanting. Fiona frees Adam from his faith, but it’s a liberation without hope. Adam writes a pleading letter to Fiona: ‘I need to hear your calm voice and have your clear mind discuss this with me. I feel you’ve bought me close to something else, something really beautiful and deep but I don’t really know what it is. You never told me what you believed in…’

She doesn’t respond. So Adam, this innocent, this boy with the name of the first man, this believer stripped of his belief with a kiss from Fiona, metaphorically and literally as it turns out, returns faithlessly, yearning for martyrdom, to his faith. As Fiona reflects: ‘There, in court, with the authority and dignity of her position, she offered him, instead of death all of life and love that lay ahead of him. And protection against his religion. Without faith, how open and beautiful and terrifying the world must have seemed to him… Adam came looking for her and she offered nothing in religion’s place, no protection, even though the Act was clear, her paramount consideration was his welfare… She thought her responsibilities ended at the courtroom walls. But how could they? He came to find her, wanting what everyone wanted, and what only free-thinking people, not the supernatural, could give. Meaning.’

Art, in particular music, that ‘horizonless hyperspace… beyond time and purpose’, is offered up as an answer, a promise, a refuge, but it remains, as it must, just out of reach. McEwan’s honesty is striking. In The Children Act he reveals the limits to the secular rationalism he otherwise champions. A disconsolate worldview, one that almost invites the religious fervour as a response, is laid bare.

Tim Black is deputy editor at spiked.

The Children Act, by Ian McEwan is published by Jonathan Cape. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.