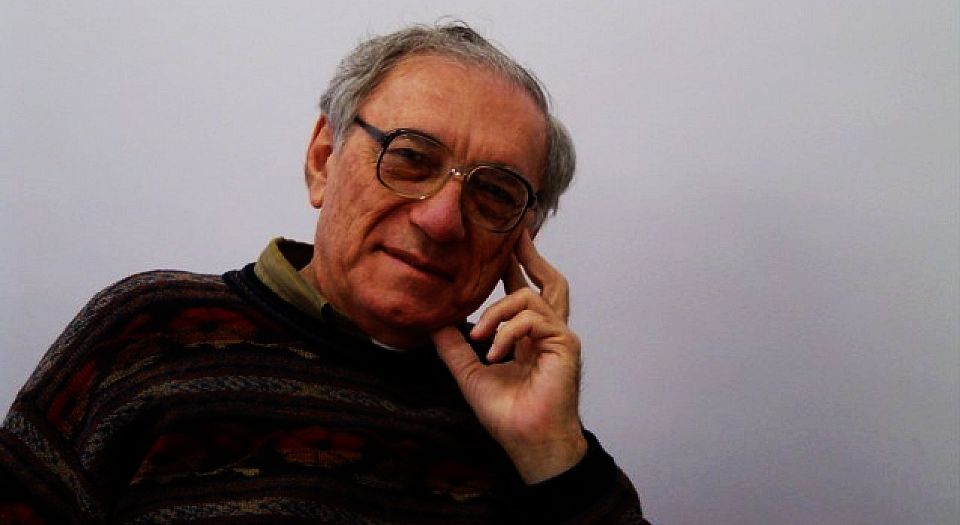

A Syrian defender of enlightenment

Remembering the great philosopher, Sadiq Jalal Al-Azm.

On the bright, clear morning of 5 June 1967, a young Syrian philosopher awoke to a phone call from the poet Adonis. Israeli and Egyptian troops had started mobilising on the border of the Sinai Peninsular, and would shortly clash in what became known as the Six Day War. Gamal Abdel Nasser, then president of Egypt, was increasingly committed to the project of Arab nationalism, and to the idea of retaking Palestine. And Sadiq Jalal Al-Azm, the Syrian philosopher in question, who died this week, had by then completed his PhD at Yale, written his first book on Kant, and taken up teaching at the American University in Beirut. That morning, Adonis told him war had broken out between the Israeli and Arab armies; they spoke with optimism about an Arab victory that would prove to be premature.

Early radio broadcasts seemed to confirm the two men’s initial confidence. There were reports of Israeli planes falling around a rapidly advancing Arab army. Yet on the following Sunday, not even a whole week later, a ceasefire was signed and the Arab forces were defeated. It cost them East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and around 18,000 casualties.

How did people get it so wrong? The first responses to the defeat were theological, with some arguing that the Arabs lost because they were too secular — they had left God, and so God had not led them to victory. There were arguments that the defeat was caused by ‘remoteness from religion and faith’, and folkish, idiotic claims that the war was not between Israelis and Arabs, but rather between ‘the Jews and Jesus Christ’. Much of this was taken seriously in intellectual circles. What was unacceptable at the time, and indeed profane, was to suggest that perhaps this defeat demanded some self-criticism among Arabs.

Sadik Al-Azm changed all this. He published Self-Criticism after the Defeat in 1968. There were 10 consecutive printings of it, to keep up with the demand among Arab publics, despite the fact that it was officially banned in most Arab countries. It was a necessarily contrarian essay, stressing the need for society to liberate itself from supernatural guarantees; to see science as a social good; to liberate women; and to modernise culture. It propelled Al-Azm into the public and intellectual arena.

Following its publication, Al-Azm was dismissed from his position at the American University in Beirut. Not only had he written this controversial book, but he had also signed a petition urging the withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam. This and other censorious responses to his book only helped to prove his initial claim: that the regimes and intellectuals of much of this part of the world were not prepared to think critically about themselves, or even to accept criticism from others. Later, the University of Damascus thankfully appointed Al-Azm as professor of modern European philosophy – a position he held for over 20 years, during which time he wrote extensively on Kant and critiqued the increasingly popular theory of Orientalism. Later, in 2010, he was effectively exiled to Berlin after falling out of favour with the Syrian authorities.

In 2013, a collection of his writings were published, under the title Critique of Religious Thought. This stands comparison with any of the 20th century’s serious, intellectual handlings of religion. There is a yearning in its prose for contemporary, secular and scientific approaches to religious thought. In the introduction to its latest translation, Al-Azm noted that the book had been banned in every Arab country except Lebanon, adding with typical sardonicism that, as a result of surreptitious publishing, it was nonetheless ‘available to anyone, in any Arab country, who wants to read it (or burn it)’.

What would become, one fears, of the hysterical ululation industry should it run out of books to burn? Hysteria again ensued, and the Grand Mufti of Lebanon successfully brought Al-Azm to trial for ‘inciting confessional strife’. I’m not sure a greater compliment can be paid to a philosophical work on religious thought than to say it caused ‘confessional strife’.

Al-Azm did not only argue against the censoring of his own works. In the 1980s, he was one of few Arab voices who campaigned, wrote and petitioned on the side of Salman Rushdie against the Iranian fatwa.

Al-Azm, unlike some in the West, it must be said, thought defending Rushdie was of great importance. Indeed, his long essay on the matter was titled ‘The Importance of Being Earnest about Salman Rushdie’. In that, Al-Azm drew comparisons between Rusdhie as a Muslim-born dissident and the literary-critical dissidents of the old Soviet bloc. The difference, he suggested, is that where the dissidents of the Soviet bloc won Western liberals’ unerring support, Rushdie did not. Moreover, rather than merely arguing for the right of The Satanic Verses to exist, Al-Azm championed its merits, too, discussing Rushdie alongside Joyce and Rabelais.

Looking back at the life of someone like Al-Azm, it is tempting to focus on the false prophets who stood against him and had his work banned and burned. And of course we should remember, and challenge, the Grand Muftis, government officials, departments of education and feeble publishers who punished or undermined Al-Azm simply for what he thought and said. But ultimately, his own arguments for criticism, reason, science and rationality, for Enlightenment thinking itself, and for celebrating literary works in the face of book-burners and death squads, should make up our memory of him.

A few years back, he said he had never wanted to become ‘an Arab intellectual in exile’. On Sunday, he passed away, in Berlin. Having spent his life writing on Kant and religion and defending the enlightened mind against its aggressors, he died while his books were still banned in much of the Arab world and without winning the full support or recognition he deserved from European civilisation. But there is time – his work will live on, despite the efforts of some to destroy it.

Tom Ayling is a writer based in London.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.