The hypocrisy of Modi’s British critics

They demand free speech in India but support censorship at home.

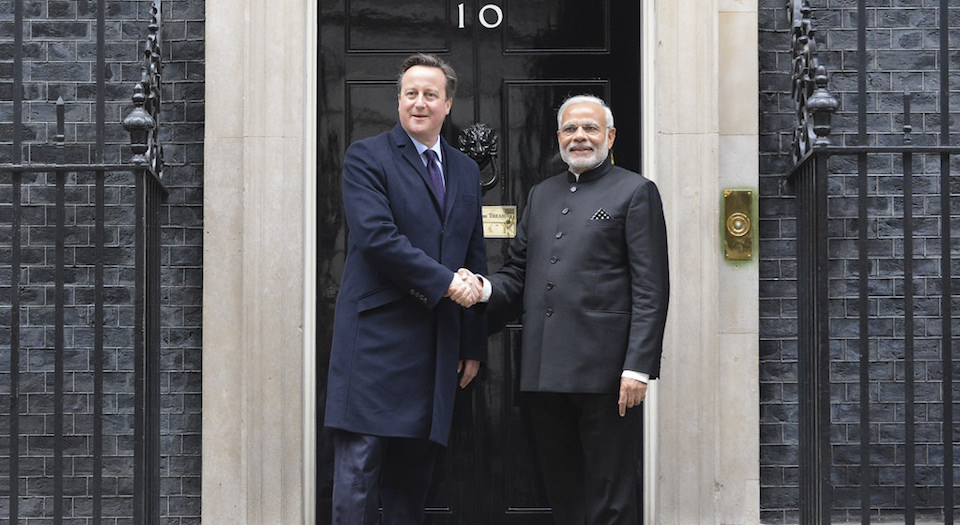

On his recent visit to Britain, the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, was greeted by a lot of finger-wagging, handwringing journalists, authors and activists who charged him with launching a clampdown on free speech. Everybody, it seemed, wanted to play their part in holding Modi to account. Authors and academics sent an open letter to British prime minister David Cameron, urging the British government to ‘safeguard freedom of expression in India’. And one Guardian journalist enthusiastically tweeted Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s plan to raise human-rights violations with Modi.

Yet those professing to be ‘committed to protecting and defending freedom of expression’ seem to be a little blind when it comes to freedom issues closer to home. After all, while they urge Cameron to ‘speak out against the current state of freedom of expression in India’, they have little to say about the assault on everyday freedoms in Britain, be it the criminalisation of so-called hate speech or the degradation of free speech on UK campuses. The self-regard with which these self-styled champions of free speech lecture an elected head of state such as Modi is not only arrogant but ignorant, too.

After all, the repression of free speech in India is hardly a new phenomenon. Moreover, it is not especially different from the attack on free speech in the UK. Both stem from an obsession with identity politics and a culture of offence-taking. While English-language commentators in India might be crying hoarse about intolerance and attacks on free speech, they often perpetuate a ritual of offence-taking. And so-called liberals, both in India and in the UK, are often very selective about which free-speech issues they deem worthy of their outrage. So a motley crew of activists – representing black women, Dalits, Indian workers and Sikh groups – was happy to gather outside Whitehall to protest against the apparently oppressive regime of Modi, while a similar crew of activists was busy in 2004 stopping the play Bezhti from being performed in Birmingham, on grounds that it was offensive to Sikhs

But it is not just the hypocrisy that grates. The likes of the Guardian and the New York Times constructed a hysterical narrative about the evil that Modi represents even before he was elected over a year ago. That millions of Indians voted Modi into power is treated as an inconvenient aside in the sanctimonious narrative that has been regurgitated ever since his victory. So, in the electoral aftermath, the Guardian sought to find ‘the real reasons behind Modi’s victory’, as if it was not enough that a majority of people had simply chosen to vote for him. The Guardian argued that it was because Indian people had foolishly bought into Modi’s slick PR strategy. This contempt for Modi voters was captured by one commentator’s dismissal of them as ‘uber-nationalists’. Little wonder, given the anti-Modi hype, that the Guardian carried the preposterous headline: ‘India is ruled by a Hindu Taliban.’ Facts and nuance become irrelevant if the purpose is to moralise from on high. Indeed, such is the self-regard of Modi’s liberal critics that they callously dismiss ordinary Indian people, characterising them either as fanatics or vulnerable fools.

In the shrill, self-righteous denunciations of Modi, there is no room for nuance, consistency or a commitment to the truth. India is not perfect now. But neither was it before Modi’s rise. There have been many bloody communal riots since the partition of India in 1947, and many under the often-ruling Congress Party. In 1984, for example, following the assassination of Indira Gandhi, nearly 3,000 Sikhs were killed in a pogrom, allegedly at the hands of Congress Party workers. When questioned about it, prime minister Rajiv Gandhi famously said, ‘when a big tree falls, the earth shakes’. Recently declassified British government documents suggest Rajiv Gandhi even asked the then British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, to curb Sikh protests in the UK, or face trade sanctions.

Indian political parties and personalities of all hues have sought to restrict freedoms – be it to protect the sensibilities of hurt Muslims or outraged Hindus, or to insulate favoured political leaders from criticism. A 2010 Spanish novel, allegedly based on Sonia Gandhi’s life, was banned under Congress rule and only released recently under the Modi government. Furthermore, between 1970 and 1980, numerous books were banned for either criticising government policies or delving into the lives of the first family of Indian politics – the Nehru-Gandhis.

India is a country of over a billion people divided along caste, class, regional, religious, tribal and linguistic lines. With over 300 registered political parties, politics is marked by opportunism, identity politics and populism. Socially, too, the contradictions of progress, ambition, prejudice and backwardness can appear baffling. But the rhetoric and moral grandstanding from the British intelligentsia and liberal press against Modi amounts to little more than a performance. If they were truly serious about freedom of expression, they would start with taking a principled and consistent stand against censorship at home as well as abroad.

Sadhvi Sharma has a PhD in International Political Economy from the Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and is a researcher-writer based in London.

Picture by Number 10

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.