Being mentally ill: the new normal?

Everyday challenges are being rebranded psychological crises.

‘Quarter of a million children receiving mental-health care in England.’ This news headline ought to shock. But, for many of us, it will barely raise an eyebrow. And little wonder, given that for well over two decades now we have been treated to one lurid report after another warning that mental illness is on the rise, that its prevalence is far greater than we previously thought, and that it afflicts all groups in society.

There never seems to be any good news to report on mental illness. Last week, a widely cited report claiming that 28.2 per cent of young women have a mental-health condition was hogging the headlines. A week before that, the focus was on a mental-health crisis afflicting university students. And before that, we were being told of the rise of mental illness among children.

The rhetoric of mental-health scaremongering has become so integral to public life that individuals and groups promoting a cause often adopt it to validate their case. Last month, for instance, opponents of payday loans in Scotland sought to strengthen their argument by asserting that ‘payday lending is putting people’s health at risk by increasing debt and anxiety among those who are already vulnerable’. Or, to take another example, opponents of the government’s austerity policies claim that benefit cuts are causing depression rates to rise. It seems that virtually every social problem, every political challenge, seems to have dire mental-health consequences.

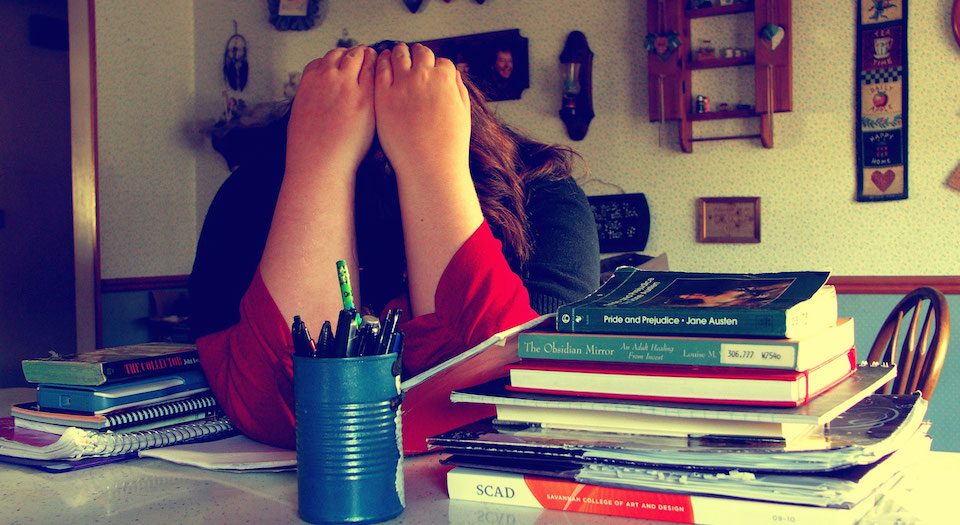

One of the consequences of the widespread promotion of mental-health catastrophism is that being mentally ill is fast becoming the new normal. This is especially true among mental-health proponents’ main target: the young. Indeed, over the past couple of decades there has been a constant stream of reports and publications claiming that children and young people have never been as anxious, depressed and insecure as they are today. Hence among the media and policymakers, the narrative of a ‘generation in crisis’ has firmly taken hold.

Of course, a sense of alienation and existential insecurity has long characterised being young, from the Romantics to the Beats. What has changed, however, is that youthful angst and insecurity has both been medicalised and, increasingly, inflated.

Take the advocacy report No Place For Young Women, published by the Young Women’s Trust in September, which claims that 51 per cent of young people feel worried about the future. What does this actually mean? One can imagine a similarly high percentage of young people being worried about the future in 1914, 1929, 1974 and so on. It seems unlikely that past generations of young people felt any more secure about the future than young people do today. In fact, I’ve rarely met any teenager or twentysomething who isn’t worried about the future. But there is a crucial difference: today, an individual’s concern about the future seamlessly mutates into a mental-health issue. It’s not a surprise, then, to find the Young Women’s Trust meshing anxiety about the future with mental-health issues, even stating that 33 per cent of young people are ‘worried about their mental health’.

To state that one in three young people is concerned about his or her mental health is usually based on little more than participants’ quickfire responses to the question ‘are you concerned about your mental health?’. Such a response tells us very little about the factors that affect a participant’s state of mind, from their physical health to their personal relationships and economic security. Certainly, there’s no reason to think that concern about the future is linked to a form of mental illness.

Not that that stops mental-health advocates from transforming ‘concerns’ about the future into evidence of a generational crisis. ‘Make no mistake’, stated Dr Carole Easton, head of Young Women’s Trust, ‘we’re talking about a generation of young people in crisis’. This conceptual leap from individuals’ concerns to evidence of a generational crisis is a good example of how everyday problems and worries are being interpreted through the language of crisis.

The construction of this idea of a ‘generation in crisis’ rests on the transformation of everyday challenges into risks to mental health. Take, for example, the claims that higher education is in the grip of a mental-health crisis. These claims are often based on the banal non-insight that students may find the transition from school to university stressful and challenging. Until recently, of course, such transitions were perceived as normal, if difficult, moments in the life-cycle. But with the growing tendency to medicalise the problems of existence, the experience of transition has been pathologised.

Initially, it was young people’s transition from primary education to secondary education – in other words, ‘going to big school’ – that policymakers considered problematic. It is only more recently that we have seen the medicalisation of the transition from secondary education to higher education. As the Higher Education Policy Institute asserted in a recent report: ‘Points of transition are associated with increased risk of developing mental-health problems, due to the stress of adapting to new circumstances.’

Many of those medicalising the process of entering higher education are aware of the question their work raises – namely, why did past generations of undergraduates make this journey without suffering adverse consequences? But their answers are conspicuously feeble. For instance, some argue that many of the new cohort of undergraduates come from non-traditional backgrounds and therefore find it uniquely difficult to adapt to their new environment. Catherine McAteer, head of University College London’s student psychological services, said that ‘what’s happening is that students are now coming to university when previously they would not have come’. Yet there is little evidence to support this claim. Moreover, students from relatively affluent backgrounds are no less likely to request mental-health support than those from less well-off backgrounds.

The medicalisation of young people’s existence

The principal driver of the constant increase in the diagnosis of mental illness is the set of cultural forces that normalise human vulnerability. As I argue in my forthcoming book What’s Happened to the University?: A Sociological Exploration of its Infantilisation, current cultural and socialisation practices encourage young people to perceive themselves as vulnerable and emotionally fragile. The cultivation of vulnerability is a cultural accomplishment that transcends social and class differences. Once young people are encouraged to consider themselves vulnerable, they often interpret their experience of disappointment and distress through the prism of psychology. Indeed, being vulnerable often becomes an important part of an individual’s identity.

Most accounts of the proliferation of the identity of vulnerability refuse to acknowledge the cultural influences that shape this outlook. For example, reports that universities are finding that ‘more students arrive with existing psychological or mental-health conditions’ blame factors that are extraneous to the influence of therapy culture. So one account claims that ‘students are seeking help against a backdrop of mounting pressure to get the best possible degree, in order to secure a good job to pay off their debts from students loans’. Others point the finger at peer pressure, homesickness, feeling out of place in a strange environment, etc. The main reason why the cultural drivers of mental-health catastrophism are not acknowledged is because so many practitioners have internalised their underlying values and assumptions.

It is important not to confuse the growing numbers of mental-illness diagnoses with an increase in actual medical conditions. There are many contingent and cultural reasons why diagnoses are increasing. For many parents, for instance, a diagnosis of ADHD for their children provides reassurance that their child’s behavioural problem is not their fault. Sometimes a diagnosis provides a claim for resources. And sometimes it gives meaning to people’s sense of distress. That is why, quite often when people talk to each other about their mental-illness diagnosis, they are not so much making statements about their medical conditions as they are about who they are as a person.

Mental-health catastrophism does no favours to those who are genuinely suffering from an illness. There is a real mental-health crisis, but it has little to do with the supposedly unprecedented problems facing the younger generation. The real scandal is that scaremongering about mental health is distracting attention from the predicament facing mentally ill people who actually need treatment.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, Power of Reading: From Socrates to Twitter, is published by Bloomsbury Continuum. (Order this book from Amazon UK.)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.